Dr. Timothy Shank: Video Transcript

Hear Dr. Shank talk about his job and the North Atlantic Steppings Stones 2005 exploration. Download (mp4, 131 MB).

Introduction

I'm Tim Shank. I'm an assistant scientist from the biology department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Things I enjoy most about working at sea are being out there with the animals. I'm a deep sea biologist. I want to see the animals. I want to touch the animals. I want to learn more about them. Every time you bring back animals, you'll learn something. It's often that we find a new species on the deep Atlantic Stepping Stone cruise. There may be half a dozen new species that we encounter and that we learn about that have some novel morphology; something that we haven't seen before. Just, so it's working with the animals. That's first and foremost. Then there's working with the people that share a common dedication to doing exploration and research. And it's incorporating your goals with theirs and being exhausted at the end of the cruise. Knowing you accomplished all these great things.

My job really consists of many facets. When I'm in my office, I'm writing research proposals, creating new ideas, new projects. I'm also writing research papers on what we found and the analysis that we've done.

The goals of my research are really to understand the ecological and evolutionary processes that structure marine diversity. Species that we see. Why are they where they are? How are they so diverse? How did they become to be so diverse? So my focus.., my research really is on hydrothermal vent systems as well as hydrocarbon seep systems around the world. But I'm also incorporating other isolated and patchy environments, like seamounts. And that was my real interest on this previous cruise. The deep Atlantic Stepping Stone cruise.

Tim talks about studying the biology of seamounts in the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Seamount Research

The cruise started in the Azores, off of Portugal, and went all the way to Woods Hole. At that time we covered over 7 seamounts from a range of depth from over 3,000 meters to 500 meters or so. We wanted to cover the range to learn the different habitats that may be. Try to see the diversity of life that's on these seamounts. It's very difficult. If you go to, think about Mt. Rainier. You're going to go to Mt. Rainier. You're going to go with a hot air balloon, at night, with a spotlight. And we want you to characterize the animals that might live on Mt. Rainier. In the trees and where they are and all that kind of thing. So OK, GO! You've got 24 hours, maybe even less than that. Very difficult to do and yet we pulled it off. We really pulled it off going to all these seamounts as stepping stones; mapping them, sampling them. When I think back on it, we did a lot of work.

Over the past decade or so, there's been much more work on Pacific seamounts than Atlantic seamounts. And one thing that came from our cruise in particular was, "What does it take to really understand and characterize the biology of a seamount." And I don't think it's been done anywhere and we made that observation and came to that conclusion on the cruise. There's Pacific seamount. There's been much more coverage. Understand species distribution much better. But we still don't know some of the first order questions. "What's where? How does it get there? What's controlling that distribution?" We know that fisheries have been more prevalent in the Pacific which may have impacted the regional species pool in general. We know it's occurring in the Atlantic. We can characterize that now. We don't know really what effect that's had on the regional species pool.

There's so much work to be done. I feel like we're just scrapping the surface of both the Pacific and the Atlantic with these first order questions. What's there? We're mapping. We're going to infer from genetics. How they're getting from one side to another. Once we start peeling back the layers of the onion, we're going to have a much better sense of what's happening in both oceans. I don't think right now we can say anything categorically other than we know some seamounts have endemic fauna. Fauna that's only found there and very distinctive. Others have shared. I mean, we're just seeing patterns you know? We're just now trying to start to get to the process. So far, in the field of marine science, there are many model systems that have been used. That's basically been the inner title system where you can manipulate, do experiments, and those have been applied to the deep sea. I think what we're going to be learning in the years to come is that some of these deep sea environments like seamounts and vents, that are isolated and patchy, are going to be actual models in themselves that will be applied to the inner title. I think a lot of that's going to have to do with genetics. What we're able to gleam from these isolated populations and their evolutions. It's going to be a remarkable time for discovery because we're going to apply genomic techniques now. We are going to learn so much more quickly about these animals than we have before. It's going to a step, or rather, jump in our understanding of evolution in the deep sea. It's going to be in part based on genetic information we are able to get from these animals. That's going to come from genomic studies that are being done on microbial systems of all things. So it's a very exciting time to, not only explore things in our world, but to explore our research techniques as well. Like genomics.

One of Tim's roles on the North Atlantic Stepping Stones exploration was to help plan dives.

Role During the Expedition

On the Deep Atlantic Stepping Stone cruise, my responsibility was to lead one of the two groups out there in looking at the evolutionary questions. How these populations have been maintained over time. These seamounts may be stepping stones for populations and we try to asses whether that's true or not. How fragile these systems are for these populations. My goal was to obtain the needed samples to address the questions that we're addressing as well to make sure that other people got what they needed out of the cruise. When you're leading a cruise out there you got to make sure everybody comes off with what they need. Not just what they need, more than what they need. That's the real goal and that's what makes the cruise really exciting; a lot of different people doing different works.

In these exploratory type missions, when you're bringing multiple investigators together, all have somewhat similar interests but certainly have their own defined goals. It becomes a real planning challenge and we had several meetings before this cruise even took place and a meeting with Peter Auster and other people to make sure we all achieve what we want to achieve. And that continued up to the very last day and even now we're doing it in terms of how we want to present our results and get our data out there. It's a challenge but it's a fun challenge and it takes constant communication. We wake up in the morning and we talk to each other immediately at breakfast about what we're going to do, what happened, you know, just a few hours ago. Because with this exploration type, things.., you go and you learn something as you go. And so your decision matrix changes over time. And so I'd often get up in the middle of the night and say, "OK Less, what happened in the last 3 hours while I was sleeping, that's going to change what we do tomorrow?" We'd have discussion about that. They were often tough decisions because it means if we pick up and leave, we'd get more time somewhere else to do more. But if we stay here we could get a little bit more done. Maybe get some more samples, animals, maybe do some more mapping; learn more. So it's always a give and a take and a challenge; and it's a balance.

And so it was thrilling to work with such great people. I think all of us were really happy about our results from the cruise.

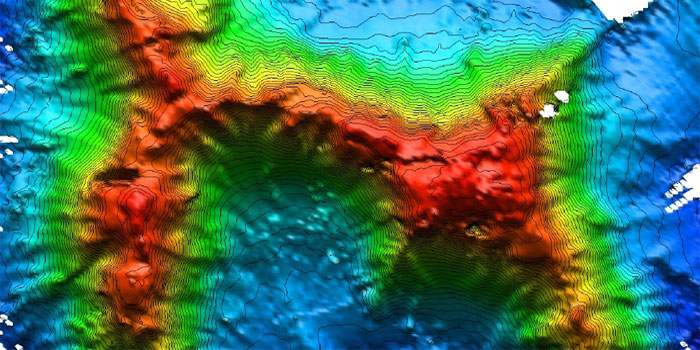

Some of the more specific things I did on the last cruise were to plan where the dives were going to take place. These are seamounts that have never been visited before. We would go first and foremost mapping using a multi-beam symmetry system on the ship. With that map, we'd look at the geometry, if you will, of the seamount to see where there might be ledges where animals like coral love to be; in the flow of the currents on hard bottom. So we try to pick those locations. And again, we're trying to make sure the goals of my group, which were getting the animals associated with the coral, not the corals themselves per se, as well as those who wanted fossilized corals for their research or want other types of coral for there research. So a part of my job was to pick those sites where we'd be diving and figure out when we'd get in the water. When we'd have to be out of the water to get to the next site and map the next site. A lot of linguistically things had to happen. Deciding who gets what lab space and who needs what, to who's going to stand watch with a remotely operated a vehicle system. We have three watches that have to happen. You have to pair people up so we have a specialist for each one of those for a certain thing. It gets quite complicated in many ways. That's all in preparation. Then there's the recovery of the animals that takes place. During the watch, with the RVs on the bottom, you're selecting which ones you want based on the questions you have. Which species you're looking for. We get those on the vehicle. The vehicle comes up. Now there's a whole other suite of things that have to happen and be organized and be directed. And basically it's making sure everybody understands their job and is doing their job like a well-oiled machine. We did a fantastic job.

Tim talks about some of the discoveries that were made on the expedition..

What Was Learned on the Expedition

I learned many things on this cruise. I'm a hydrothermal vent biologist for the most part working in chemosynthetic habitat. This was really my first cruise to look at seamounts. The reason why I want to look at seamounts is because the populations are somewhat similar. They're isolated. Hydrothermal vents are discreet patches on the sea floor along the ocean ridge system. Well, populations on the sea mounts are very similar. Seamounts are very isolated too. So for me, it was seeing just how patchy these communities were. It was so amazing. There would be stretches of hard bottom sub stream that you'd think they would love to be on and they're not there.

Then all of a sudden you come around a corner and there they are. It's clear to me by depth they were isolated and by distance they were isolated and that was the immediate impression that I got. It's helping to form my ideas about what isolation really means in the marine environment and that's going to help me with all my work the proceeds; that goes on from this.

The other thing, we saw such intimate relationships between the invertebrates. The crabs, the sea stars, with corals that I didn't think we would see, exactly. We know that coral provides habitat. They're very important for habitat for lots of different animals. Things we call ophiocreas and sea stars, snails and worms and crabs. I could go on, but what I didn't think we would see is that certain coral have certain species on them only. Certain corals have one sea star. That sea star lives there his whole life and other sea stars don't get in there somehow, for some reason. Another black coral, for example, has these crabs on it. What we call squat lobsters. There're two crabs on there. One's a female, one's a male and the female seems to always have eggs. And how they find these corals that may be kilometers apart. I mean they're very sparse, they can be. How they find these things. How they disperse from one seamount to another could be thousands of kilometers, and they find this little thing that sticks up a foot out of the seafloor. It's just fantastic! And that's what we're trying to figure out.

We're going to compare the genetics of crabs from one seamount to another that live of these black corals. And tell us how they're migrating with the corals somehow... they figured out some strategy to do it. They're doing it really well and I never expected to see such intimate relationships among some things and not among others.

Two other things that were very interesting to me are that we came across a couple of seamounts that showed extensive trauma used to be fisheries. For 20 years it was fishery activities going on at these seamounts. And one of these seamounts was completely diluted. Completely wiped out of all fauna and I had never seen that before. You could really see the trail marks that dug into the seafloor. And then I think about how long it takes these corals to grow. I think about how specific these fauna are to these corals. Take the corals away... what are these species going to do? They're all going to risk extinction, possibly. So that was a critical message to me that we've read about, people talked about it, but I saw it first hand.

The other thing was of real interesting to me was what exploration can be all about. You go out with a set of ideas and thoughts and then you find something totally serendipitously. And that's what happened to us. On the very first dive we recovered a coral species that had this round egg shaped casing on it and it had been broken open, clearly. None of us knew what it was. There was a very intelligent biologist out here. Very experience biologist that goes to seamounts and everywhere else and no one knew what it was. After a couple of dives we recovered some others ones and finally found one that was intact. I opened up the case and an egg rolled out. I took the egg and cut it open and this very small.., just a miniature octopus. A dumbo octopus is what we call it. These are cirrate octopods that have these big fins on the side of their heads that they flap. There known to the deep sea. They're considered to be quite rare. Very few have been captured live. Those that have been in museums have degraded over time so they don't know a lot about them. So we saw one. It didn't appear to be alive. Several dives later on another seamount, we saw another egg. We knew it was an egg by this time. We brought it up and in the process of getting it into the cold bucket looking at it, the egg broke open. One of these big fins flopped out and within five minutes or so this whole beast was out flapping around, swimming in the bucket. No one's ever seen this before. You wouldn't do it unless you were exploring getting these kinds of samples. I mean just spectacular natural history. I've got many octopus specialists calling me right now wanting to know more about it, learning more about it. I mean this will be the first time this has ever been seen and documented. So it's just fantastic. We've got great footage of it swimming and we're just elated. And so that's one of the things that will forever be etched in my brain about this exploration.

What we've done is go out to sea with certain questions, knew this was really interesting, and now we're coming back with loads more. Really focused, directed questions that are going to help build my career and keep my career going for years to come.

Tim talks about his own career path and offers advice to young people interested in studying marine science.

Closing Remarks

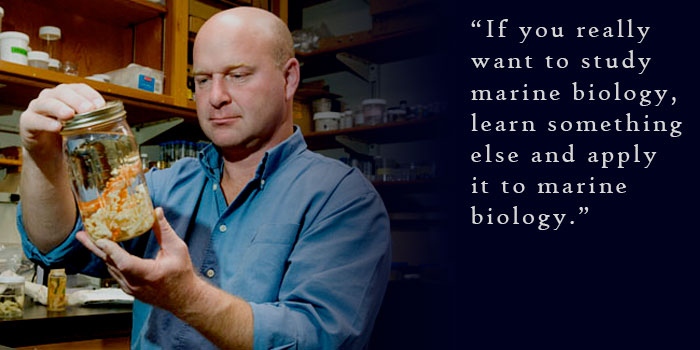

As an undergrad at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I went to my marine science professor, just had my first course with him and he had just discovered the first hydrocarbon seeps. This was in the mid 80's. And I told him I wanted to be a Marine Biologist and he said, "Well don't study Marine Biology." It was great advice. He said, "Don't study Marine Biology. Go learn genetics. Go learn computer modeling. And then bring it and apply it to questions in Marine Biology." He was absolutely correct. It was the best advice I've ever gotten. And I went and said, "Well, what's going to be really up and coming?" At that point, the preliminary chain-reaction had just been discovered so you can make many copies of genes and gene sequences. I knew genetics was going to be a big thing so I said, "Ok, I'm going to go learn genetics," and I did. For three years I worked in a genetics toxicology lab far flung from any marine system. And I said, "Ok. I'm learning the stuff. This is really good stuff and now I want to apply it to questions in marine biology." And that's what I did. I went right to graduate school to get a PhD. And I had been looking at some of the most interesting things in the deep sea and in the marine field in general. And I was just so attracted to hydrothermal vents. I think because there was so much news about an eruption that had taken place in 1991. And I said, "Ok, that's what I want to go do. I want to go study these animals that are so weird and so unique. And use these genetic tools and that's basically how it started.

I think one of the most thrilling things I've ever seen on the bottom, I've had over 50 submersible dives to the deep sea floor, maybe over thirty ROV dives, and I think.., when I first think about it, I think about the most exciting moment when I first saw the bottom for the first time. I just spent a year studying these communities at hydrothermal vents. I mapped the seafloor and knew right where they were. I was ready to see what had changed over the past year and I went down and I dove and I saw it immediately and it was like my own backyard and it was thrilling. That's not the most thrilling story to tell somebody, because it's a personal story. But there have been other things. We actually, one time, saw an octopus die on the seafloor which is very unusual. We sat there and we watched it expire which is very strange in some ways. And then we saw crabs come in immediately and start to chew on him and tear at him.

On this last cruise we saw the birth of an octopus out of an egg which has never been seen before. That was fantastic. I think I saw something from every cruise where I though, "That is just fascinating." Trying to rank those is really doing a disservice to any of them. So, I think the most fantastic thing I've ever seen was seeing the seafloor for the first time and seeing those animals.

Giving advice to upcoming, wannabe marine biologists or scientist, I'd give some of the advice I've been given in the past which is, "If you really want to study marine biology, learn something else and apply it to marine biology." It's such a dynamic and complex system to understand life in our oceans that you've got to understand something about currents, nutrition, physiology, a variety of things, the chemistry of the ocean is always very important to these animals. So I would go learn, i guess like I did, learn genetics and then apply it to marine biology. I would also give you the advice to keep your creative juices, always. Keep them flowing. Always think the unimaginable and let yourself go for it. I would also advise you to learn the system that you like a lot. Know it the best you can because all your creative ideas are going to come spinning out of that. I think I could have a lot of little advice tidbits like that. It's also too.., honestly, learn about yourself and understand yourself. Often understanding what's out there is understanding how you think about things and keeping an open mind. So, that would be my advice.

Return to profile