Published October 30, 2019

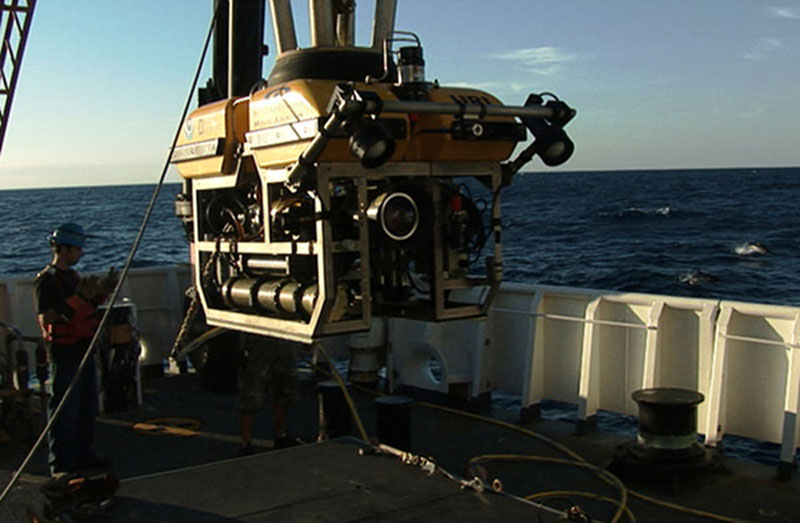

In the aftermath of the April 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico, NOAA scientists joined hundreds of environmental researchers to figure out how the oil was affecting marine life at the spill site, on Gulf coast beaches hundreds of miles away, and deep beneath the ocean. With its unique ability to send deep-diving remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to the seafloor, the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration (OER), working from NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, was ready to discover what happened to the undersea world.

Deep-sea corals flourish in the dark depths of the Gulf of Mexico, providing foundations that attract lush communities of other animals, including brittle stars, anemones, crabs, and fish. This diversity of life on the seafloor may be out of sight, but it is has been squarely on the minds of scientists seeking to determine the short- and long-term ecological impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM.

When the oil platform blew, the Okeanos Explorer was headed to Indonesia on its maiden voyage. NOAA officials decided at the time that there were already enough ships on the scene.

But after its return to U.S. waters, the OER team and Okeanos crew made several multi-leg cruises in the Gulf that filled gaps in scientific knowledge, documenting the extent of damage from the spill on the fragile deep coral ecosystem. OER built on earlier work completed by NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown in the fall of 2010, just a few months after the spill. In a joint expedition with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the crew of the vessel explored a region of deepwater corals about seven miles southwest of the Macondo well site where the spill occurred.

Within minutes of arriving, the biologists on board realized this site was unlike any others that they had seen over the course of hundreds of hours of ROV and submersible time studying the deep corals in the Gulf of Mexico over the prior decade.

In 2010, the Jason ROV imaged a site downstream from the plume flowing from the Macondo well. Scientists found deep-sea corals showing signs of recent and severe impact. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012.

“Most of the coral colonies appeared to be either recently dead or dying,” wrote Chuck Fisher, professor of marine biology at Pennsylvania State University on the ship’s web log. “Most of the sea fans (gorgonians) had large areas that were bare of tissue, covered with brown material, and/or had tissue falling off the skeleton.”

At the time, scientists didn’t know whether the oil spill would disperse in the water column over time or settle to the bottom and damage benthic life. This expedition provided an early glimpse into the damage that the spill caused.

During the next two years, researchers aboard the Okeanos Explorer found the oil had spread much further and had impacted a great number of coral ecosystems.

“Even though the well was capped in 2010, there was a huge plume of oil moving through the water column,” said Jeremy Potter, scientific coordinator of an April 2012 Gulf of Mexico expedition on the Okeanos and now chief of the environmental sciences section of BOEM’s Pacific region. “These corals were in the middle of that plume. Imagine the corals surrounded by oil, they aren’t used to it and are impacted.”

The Deepwater Horizon wellhead spewed 4.9 million barrels (or 206 million gallons) of oil over 87 days, while emergency responders dumped another 1.1 million gallons of chemical dispersants in the ocean near the site at more than 1,400 meters depth (0.87 miles).

Potter said there were key questions that the April 2012 cruise had to answer. “Even though the plume is gone, are the corals going to die or will they get better?” he said. “Nobody knew at the time.”

Using high-definition video camera on the ROV Little Herc, the team documented ecological damage with the help of technology that allowed the pilots to find the exact same corals in 2012 that had been photographed back in 2010.

Little Herc’s powerful high-definition camera systems yielded unprecedented images of coral ecosystems in the vicinity of Deepwater Horizon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012.

“Every time they would go down, they took the same picture,” Potter said. “The (ROV) pilots were amazing. It was a dance to figure all this out and do it on the fly.”

The scientists also found several additional deepwater coral areas that had been affected by the oil spill further away from the Macondo wellhead. Potter said that this 2012 expedition proved the value of the Okeanos Explorer as a vessel that could be quickly deployed to do environmental monitoring of a critical site in U.S. waters, validating the projections and environmental modeling that scientists made about where the oil would travel, and where they would find the most ecological impacts.

As a bonus, it was also the first expedition to feature live video feeds of the ROV dives broadcast to the public.