By Christina Kellogg, U.S. Geological Survey

July 18, 2012

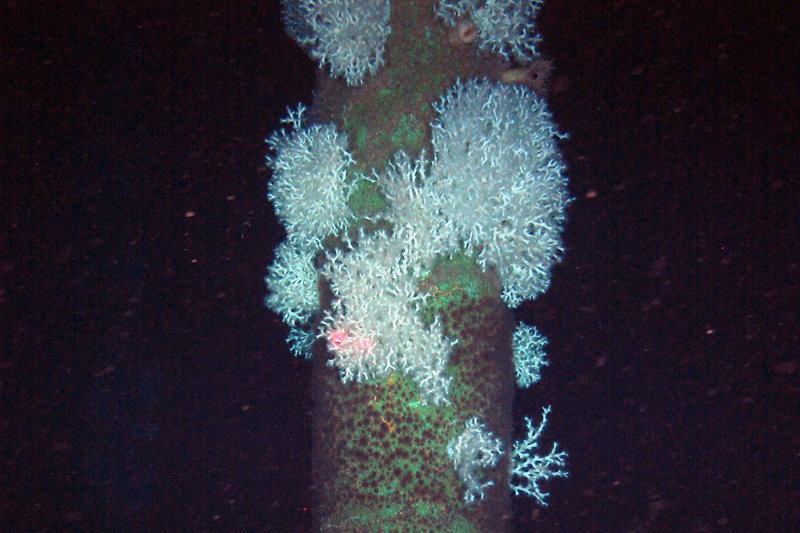

White Lophelia colonies imaged by the Kraken2 remotely operated vehicle while diving near the Joilet platform in the Gulf of Mexico. To get a sense of size, the two red dots you see are 10 centimeters apart. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 900 KB).

In fashion circles, white is a summer color. You wear it from Memorial Day (end of May) to Labor Day (beginning of September). Of course, there are no calendars in the deep Gulf of Mexico. Possibly not much fashion either.

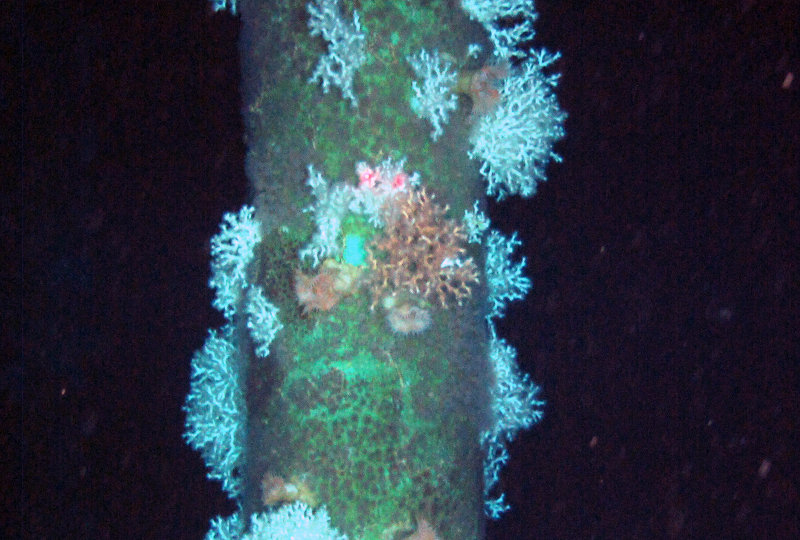

Lophelia is known to occur in two colors, white and orange (sometimes called red). In the eastern Atlantic, Lophelia reefs near the United Kingdom or in Norwegian fjords have both colors. They can be found growing side-by-side. In eight years of doing Lophelia research in the Gulf of Mexico, I’ve only ever seen white colonies. As we were imaging the Jolliet platform on Tuesday, we saw what may be two orange colonies among the many white ones. While we would need to collect actual samples in order to confirm that the orange coral is in fact Lophelia, the possibility that we’d just spotted the orange variety resulted in a lot of excitement.

Nobody knows why there are two colors of Lophelia (as opposed to only white, or multiple colors). We do know that Lophelia eggs can be either white or orange, so that suggests the color is a genetic gift from the mother colony. We also know that only the coral tissue is colored; the skeleton underneath is always white.

A possible rare (for the Gulf of Mexico) orange Lophelia colony seen during a remotely operated vehicle dive near the Joliet platform. Sampling would need to occur to tell for certain that this is in fact Lophelia. The two red dots you see are 10 centimeters apart. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

People wondered if the color difference could be due to a specific microbial associate. In tropical corals, some species are brown at shallower depths and bright orange at deeper depths. The bright orange color comes from cyanobacteria. A study has shown that there is a difference between the bacterial communities on white versus orange Lophelia from a Norwegian fjord, but no specific bacterial group was dominant the way cyanobacteria are in the shallow-water coral example. What’s more, using the same methods, the bacterial community on white Gulf of Mexico Lophelia more closely resembles that of orange Norwegian Lophelia rather than white. Also, Lophelia eggs do not appear to have any bacteria inside them. So while the color may influence the associated microbiology, it does not look like the microbes are responsible for the color.

People wondered if the color difference could be because the orange colonies were really a cryptic species – something that looked a lot like Lophelia, but really wasn’t. Coral geneticists have looked at both orange and white colonies and they are not separate species.

So why be orange? The white corals are basically colorless so that the white skeleton shows through. These corals live deep in the ocean and do not photosynthesize (because they live in the dark and have no algal symbionts) so they have to get their energy by using their tentacles to grab little particles of food drifting down from the surface. If you have to work that hard, there should be an important reason for spending some of that energy to make a pigment. Does being orange render those colonies invisible to some coral-munching predators? Does it attract zooplankton that could be dinner? Or is it just a fashion statement?