By Kirstin Meyer, Ph.D. Student - Oregon Institute of Marine Biology

May 20, 2013

Multiple catsharks and catshark egg casings rest on suspended fishing line. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 1.9 MB).

For my dissertation research at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, I am investigating the role of intermittent hard substratum (underlying layers) in structuring benthic (bottom) invertebrate communities. Structures like drop-stones, underwater cliffs, seamounts, and sunken ships form important habitat for diverse life, including attached (sessile) and motile invertebrates and fishes.

From catsharks to sea stars, the diversity of marine life is on shipwrecks is often higher than in surrounding areas. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

During the second leg of this year’s canyons cruise, we’re visiting a series of shipwrecks on the outer continental shelf. Anyone watching the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) video feed will immediately notice that there are much greater abundance and diversity of organisms around the shipwrecks than anywhere else in the field of view. You can feel it coming – as the ROV hovers over the soft sediment, passing only the occasional sea star or crab, gradually there begins to be debris on the sediment. We pass sea urchins and more crabs, and then come the catsharks – lots and lots of catsharks. Finally, there it is! The ROV approaches a sheer vertical wall covered in hydroids and anemones: the ship.

Not all shipwrecks have a complex superstructure – some may constitute as little as pieces of wood, ballast bricks, or the occasional canon – but the shipwrecks we are visiting are large and complex. Many of them are populated by hydroids, anemones, sponges, and other sessile organisms.

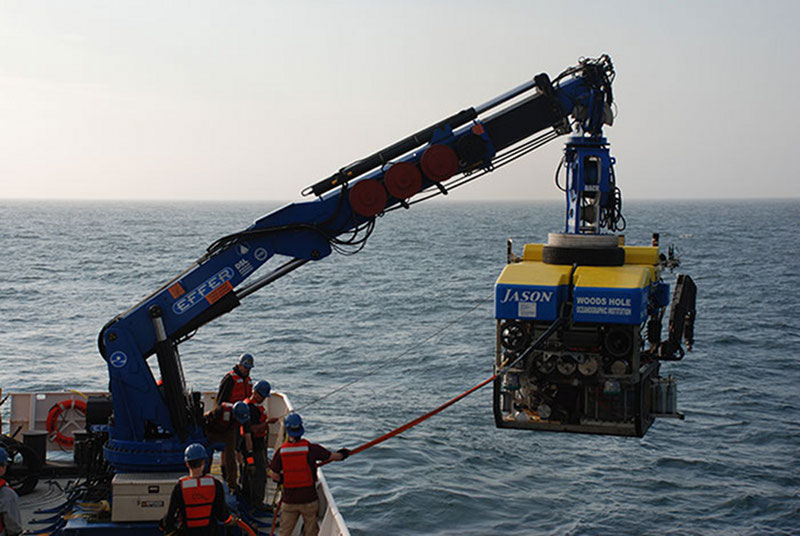

The Jason remotely operated vehicle is lifted into the water for the first dive of Leg II. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 4.5 MB).

As I analyze the ROV video from the shipwrecks, I’ll classify the organisms I find by feeding type. I suspect that soft-bodied filter-feeders settle and thrive on the shipwrecks because they are able to settle high off of the ground – out of the benthic boundary layer – so they experience faster currents that facilitate filter-feeding.

I’ll also be analyzing the similarities between the species found on each shipwreck. The wrecks form a sort of natural experiment, all having been sunk at about the same time at varying distances away from each other. I hypothesize that the shipwrecks that are closest together will have the most species in common, and that the wrecks the farthest away from one another will have the least species in common.

While on board the cruise, I have the chance to collect good, statistical video from the shipwrecks. In order to do an accurate statistical analysis, I want video recorded while the ROV is traveling at a constant speed and is a constant distance away from the wreck. That way, I can tell exactly how much surface area has been covered in a particular segment of video and calculate how the abundance of organisms on the surface of the wreck (percent cover and/or density).

Jennifer McClain-Counts processes samples collected from shipwrecks. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 5.0 MB).

For size reference, there are also two parallel lasers fixed 10 centimeters apart above the camera. These are particularly helpful if the ROV gets swept up by a current or has small variations in speed or distance. The laser points show up in the video, so I can use them as a reference to determine the area surveyed and relative sizes of organisms.

Lastly, the ROV can collect voucher specimens of each of the species observed in the video. By examining the voucher specimens back in the lab, I can determine exactly what species are present on the wrecks. Because many species look alike, it’s often not possible to determine the species from the video alone. A physical specimen helps me ensure I know the correct species name.

I’m looking forward to having a great cruise and collecting good data!