John Bright, Maritime Archaeologist - Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

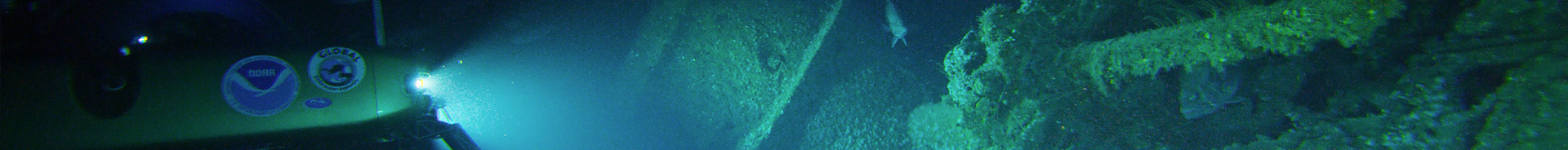

U-576 at the dock. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download image (jpg, 112 KB).

Seafaring and warfare are two of humankind’s oldest activities. Just as past cultures traversed great distances over water for commerce, trade, and exploration, so too did they use maritime transport for the purposes of warfare and conquest. Not surprisingly, then, is the fact that chronicling, studying, and researching warfare (and seafaring, too) are nearly as old as the activities themselves. Take for example Homer’s The Illiad and The Odyssey, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Virgil’s The Aeneid – classical texts dealing heavily with the topic of conflict at the nation-state level.

Thus, the study of warfare and maritime history progressed like most fields of study through the ages: slowly coalescing and refining into increasingly articulate and formalized academic endeavors. Battlefield archaeology emerged as a sub-discipline of archaeology during the 1950s, as American and European scholars focused on understanding terrestrial (land-based) battlefields across the European and North American continents. Here, researchers used archaeological remains (the physical remnants of encampments, fortifications, sieges, gun placements, weaponry, etc.) to review and reassess historical (written) accounts of battle events. In many cases, this archaeological component of battlefield research added important details simply not present in the historical record and could also correct inaccuracies within accepted narrative accounts—overall increasing the understanding of a given battle or military action.

In the ensuing decades, advances in analysis methods allowed archaeologists to understand physical remains along battlefields in even greater detail. Ground-penetrating radar, forensic analysis of projectile remains, digital reconstructions, etc., offered new perspectives on battlefields. A common thread throughout all of this growing research was the need to relate archaeological remains on a battlefield to the surrounding landscape and, more broadly, to understand these actions within the context of the actual principles of military action at the time of the battle.

Numerous codified military treatises have been written throughout the ages, many forming the foundation for strategic military doctrine for the era in which they were espoused. To understand strategy during the American Civil War, for example, a researcher could reference the military doctrine taught to the students—later Union and Confederate officers—at The United States Military Academy at West Point.

In fact, many of the strategic and tactical principles employed during the American Civil War were still relevant to combatants during the First and Second World Wars. Though technology varied considerably between the 1860s and 1940s, the principles through which military commanders framed their application were still fairly similar. The specificity with which tactical principles were articulated, however, was far greater during the Second World War—the U.S. Navy had an entire series of manuals for anti-submarine warfare, just as the German Navy had dedicated manuals for U-boat operations—though the principles themselves were essentially the same.

At a tactical level, military commanders were still taught to reference a series of acronyms representing the essential elements of a successful military action: METT-T and OCKOA. They are defined as follows:

With Terrain further sub-divided as OCKOA

Taken as a whole, these principles and well-defined tactical descriptions of how U-boats, surface escorts, convoy ships, and patrol aircraft were instructed to operate provide a framework for WWII battlefield researchers to assess the actions of ships during a given battle as a function of the landscape, weapons, tactics, and time.

In the case of the KS-520 convoy attack, a battlefield-level archaeological assessment proved valuable for understanding why a single, damaged U-boat (U-576) attacked a large, guarded convoy. Likewise, it also helped explain the decision to install the Hatteras Minefield, the configuration and deployment of escort vessels around the convoy, and the critical role of air cover in defense of the convoy.

The battlefield archaeological approach, therefore, enabled researches to elevate study of the KS-520 convoy attack beyond the ‘who, what, when, and where’ retelling of a historical account. This approach instead answered many of the ‘why’ questions left unanswered by the historical records and directed archaeologists to conclusions about location and landscape that ultimately led them to the actual remains of U-576 and Bluefields.