By Joe Hoyt, Maritime Archaeologist - NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

September 10, 2016

Video courtesy of NOAA/2Grobotics/Sonardyne. Download (mp4, 235.0 MB).

There is a constant frenzy of activity from the time I roll out of my rack in the morning until, salt caked and tired, I crawl back in late at night. Daily mission briefs, personnel transfers, coordinating submersible rotations, assigning objectives, launching subs, downloading and processing data, reconfiguring survey equipment. It is very easy to get so caught up in the mechanics of executing the day-to-day activities of a mission that you miss the wonderment of where you are.

Joe Hoyt (right) getting into a submersible. Image courtesy of NOAA, Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

We are nearly 40 miles out to sea. Two manned submersibles are strapped to the deck ready to carry out a mission you and your colleagues have been dreaming about for years. Nearly 800 feet below you lies something unseen for more than seven decades, a monument to World War II history and the tomb of nearly four dozen men. Simply incredible.

Mikael, Jason, and Aimee (from left) discuss their work. Image courtesy of NOAA, Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

A precious few moments struck me where I could appreciate the enormity of it all. Looking around at the research team and the crew, I knew it must be the same for them. Such an incredibly talented and hardworking team has been put together for this mission and they were focused on doing a great job.

Joe Hoyt (in red shirt) during the morning briefing. Image courtesy of NOAA, Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

Jason Epp, the lead laser-scanning technician from 2GRobtics was up half the night with Mikael and Aimee from Sonardyne. They had finally integrated all of their systems with Nemo, the acoustic beacons had all been deployed and calibrated, and they were planning the first laser data collection dive. The next morning, Jason climbed bleary-eyed into Nemo juggling two-laptops. As he slipped into the acrylic sphere alongside pilot Robert Carmichael, I could tell his mind was focused solely on getting the best data possible. I poked my head into the hatch just before it closed, “Hey Jason,” I said, “It’s ok to enjoy it for a minute.” He grinned and gave me a ‘thumbs up’.

Joe Hoyt and submersible pilot Robert Carmichael (from left) inside the submersible. Image courtesy of NOAA, Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.5 MB).

From the first dives to the last, we focused first on collecting our primary data, but I am hopeful every member of the team got a few of those moments where they realized they were in a truly special place, and that the work we are engaged in has the potential to enhance our understanding of history and protect these unique sites.

Joe Hoyt taking pictures of U-576 from inside the submersible. Image courtesy of Robert Carmichael. Project Baseline. Download larger version (jpg, 4.5 MB).

We have now come to the end of a long and fruitful expedition. Trying new approaches and systems integrations while dodging tropical depressions and hurricanes presented some significant hurdles, all of which were navigated successfully. A complete downward-looking laser scanning survey was completed on both U-576 and Bluefields. Preliminary raw data is promising, and I am confident we will have accurate 3D models of these sites down to the millimeter.

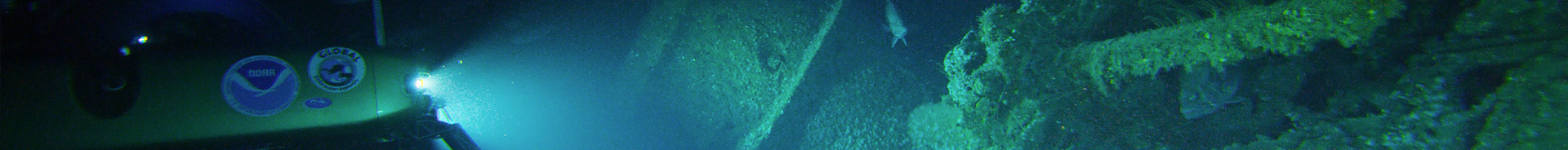

The submersible shines light on U-576. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute. Download larger version (jpg, 6.5 MB).

Photogrammetric modeling was also successful. A partially complete model of U-576 was collected and will likely compliment the laser scanning point cloud data, particularly around undercuts. Likewise, the Global Underwater Explorers and Project Baseline dive team was able to conduct the first dives to YP-389 and collect stunning imagery along with a complete photogrammetric model of the site. In all, the team came together and gathered great data with incredible results.

Wreck of the merchant vessel Bluefields. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute. Download larger version (jpg, 95 KB).

The baseline data collected on YP-389 is of particular importance, as it is within diveable depths, yet had not been previously dived. A complete record of artifacts and site integrity is now in hand that will potentially allow us to track human impacts on site in the future.

Photomosaic of YP-389 wreck site. Image courtesy NOAA, Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 263 KB).

Data collected on U-576, Bluefields, and YP-389, three sites that have never been visited by people since their loss in 1942, will prove invaluable to Monitor National Marine Sanctuary as it continues to develop approaches to better protect these resources and share this history with the broader public.

Working 800 feet deep 20 years from now may seem quite pedestrian, and we will be glad we have a complete record of the pristine remains of the KS-520 Convoy attack. These data are easily repeatable and offer an extremely accurate assessment of the status of these vessels in 2016.

The wreck of the USS YP-389, a United States Navy yard patrol boat. Image courtesy NOAA, Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 307 KB).

Moreover, we successfully tested our methodology and found that we could reliably collect these types of data from both divers and manned submersibles in this region up to depths of more than 800 feet. This represents a significant step forward in the capacity for archaeological research and resource management at Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

Although the team achieved the primary objectives of the mission, I walk away from this project feeling as I always do when such endeavors are over: Never enough time, never enough data. Though I expect with experiences as incredible as we enjoyed during this expedition, ‘never enough’ is a sentiment shared amongst the whole team, and is what always compels us to return.