By Dr. Martha Nizinski, NOAA Office of Science and Technology, National Systematics Laboratory

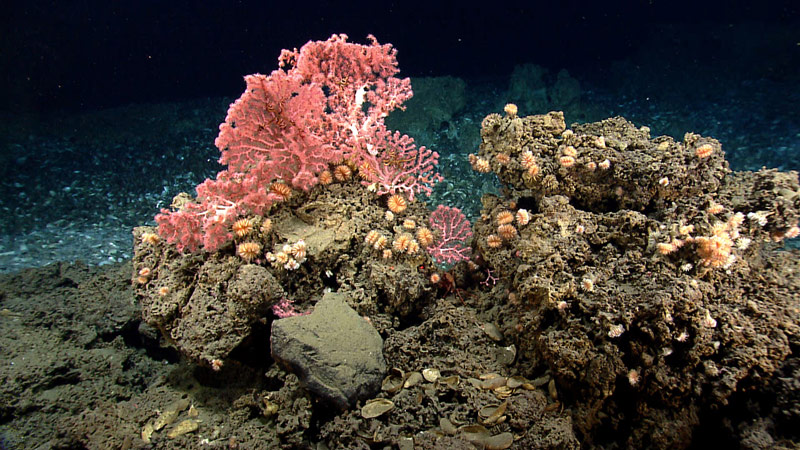

These corals, including cup corals and bubblegum corals, were found on hard substrate near the edge of a mussel bed while exploring a gas seep area near the northeast submarine canyons. Image courtesy of 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Submarine canyons are major geologic features of continental margins that link the upper continental shelf to the abyssal plain. Results of the most recent surveys estimate approximately 9,000 canyons worldwide. Even with increased research activities in recent years, most canyons remain poorly known. These geologically and morphologically diverse environments support a wide variety of habitats. Some findings suggest that increased habitat heterogeneity in canyons is responsible for enhancing benthic biodiversity and creating biomass hotspots. Patterns of benthic community structure and productivity have been studied in relatively few submarine canyons.

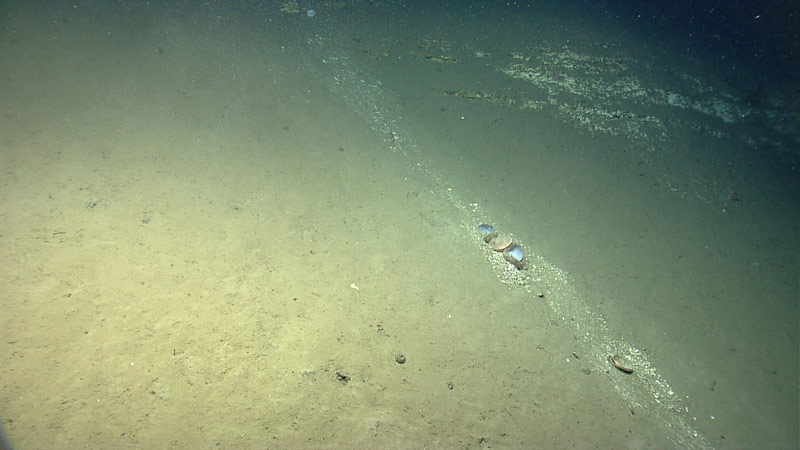

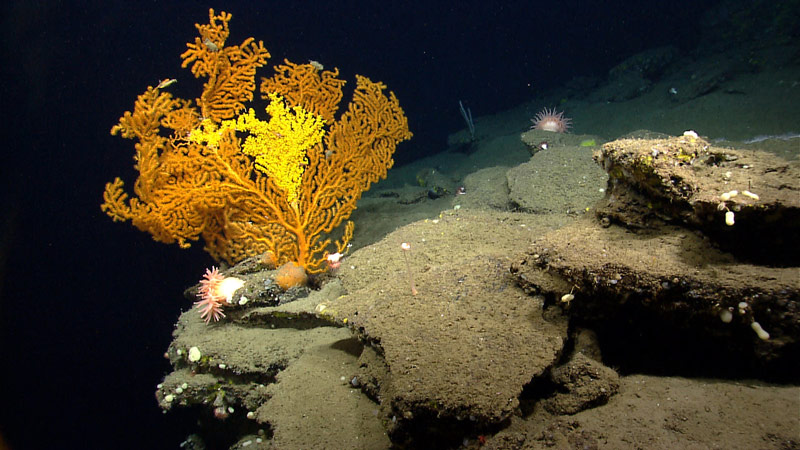

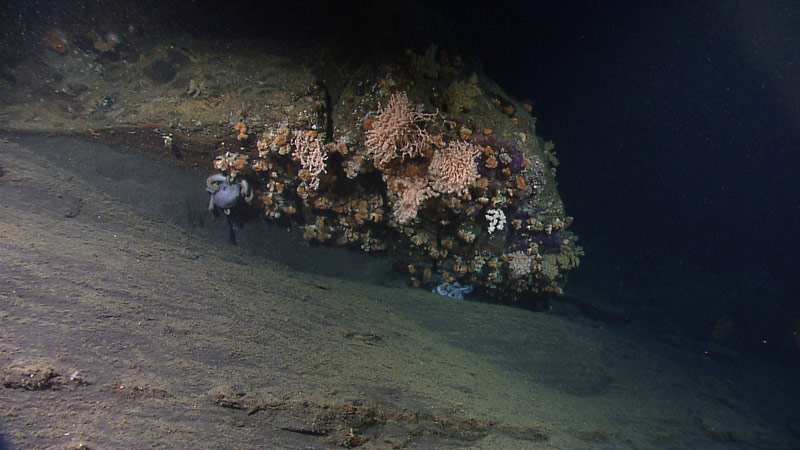

We are finding that canyons support deepwater coral communities, as well as a number of other sessile (or immobile) filter feeders, in addition to standard slope fauna. Taxonomic richness is also found to be higher in areas of exposed hard substrate. Therefore, canyons are unique in that they provide habitat for a variety of sessile taxa that are not found in other slope environments. These images illustrate the diverse array of habitats and faunal assemblages that we have observed in the Northeast canyons.

Anthomastus coral found on sandy bottom in Oceanographer Canyon. Image courtesy of 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Numerous major and minor canyons exist along the continental margin off the U.S. East Coast. The Northeast and Mid-Atlantic canyons were the subject of several recent scientific initiatives. Canyons in this region were a high priority for federal and state agencies tasked with research and management responsibilities, particularly because of deep-sea corals. Several research teams, using a variety of tools, explored many canyons in this region.

“Recent” sediment transport down the wall of Lydonia Canyon. The bivalves in the center of the image were carried downslope as part of the sediment flow. This image demonstrates the diversity of habitats and substrates that can occur. Image courtesy of 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

In 2012, Atlantic Canyons Undersea Mapping Expedition (ACUMEN) brought together stakeholders and resources to produce a focused, efficient initiative to gather information needed to protect and conserve canyon habitats, in particular, those where deep-sea corals are found. The ACUMEN mapping blitz laid the groundwork for the NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer Northeast U.S. Canyons expedition, as well as other canyon research in the region.

The Northeast Regional Deep Sea Coral Initiative (2011-2015), funded primarily by NOAA’s Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program, used a broad-scale approach, collecting contemporary data in multiple canyons. Canyons were prioritized and sampling locations selected based on data needs of the Mid-Atlantic and New England Fishery Management Councils. Twenty-four canyons were surveyed using a towed-camera system to gather data on coral diversity, abundance and distribution.

The Okeanos Explorer Northeast U.S. Canyons expedition (2013), a partnership between NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (OER) and the Northeast Regional Deep Sea Coral Initiative, explored 10 additional canyons in the region. Through live telepresence coverage, the canyons, corals, associated organisms, slope habitats, and conservation issues of the Northeast became an interest of a wider community of scientists, managers, environmentalists, and citizens.

Additionally, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), in partnership with NOAA OER and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), funded work (2011-2015) by other researchers to conduct intensive, focused sampling in Norfolk and Baltimore canyons. Results from this initiative not only increased our knowledge of sensitive habitats in the region, but also served as an environmental assessment to inform legislators and managers interested in oil and gas exploration in that region.

A Paramuricea coral in Nygren Canyon, which is 165 nautical miles southeast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Image courtesy of 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Coral diversity, abundance, and distribution data are used to better inform the councils and assist them in their decision-making process, as they work to satisfy all stakeholders in the region, as well as to protect deep-sea corals and their habitats. Both councils are proactively working to protect deep-sea coral habitat. The Mid-Atlantic council has recommended closures of discrete and broad-zone coral protection areas. The New England council is reviewing information and deliberating over potential coral protection zones.

Interest in canyons and coral habitats remains high and the geographic region of exploration and research is moving southward to include areas from North Carolina to Georgia. NOAA, USGS, and BOEM are all interested in deepwater habitats in this region.

The Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition aboard NOAA Ship Pisces will focus on three canyons off the coast of North Carolina, specifically Keller, Pamlico, and Hatteras canyons. Historically, work has been conducted in the Pamlico/Hatteras canyon system. Here, the species composition within the canyon was very different from that along the continental slope north and south of the canyon.

Currents sweep past an overhang of rock at 1,152 meters depth in Oceanographer Canyon, creating an ideal microhabitat for a deepwater coral community and a couple of octopods. Image courtesy of 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

The proposed area of operations is extremely dynamic. Perhaps most noteworthy of this region is the known transition area between the faunas of the Mid-Atlantic Bight and those of the South Atlantic Bight. The Hatteras Slope area, referred to as “The Point,” is hydrographically unique, because it is an area influenced by the convergence of three major currents: the Gulf Stream, Western Boundary Undercurrent, and the Virginia Current. Additionally, the Hatteras slope is highly unusual in that is has the highest densities of sediment-dwelling fauna along the U.S. East Coast continental slope, unusual communities of megafaunal invertebrates and benthic fishes, high sedimentation rates, and high flux of organic carbon.

The anomalous—or unusual—conditions recorded from this region likely influence the biological and physical characteristics of the canyons found in this area. Exploring these canyons is a logical follow-on that will complement our previous work. Preliminary results suggest there are regional differences between Mid-Atlantic canyons and those canyons further north, and results from previous studies suggest that a partial zoogeographic barrier exists on the slope off North Carolina. Our surveys in the Carolina canyons will help to identify and characterize the community structure and geological characteristics of these southern canyons. This new data will allow us to make detailed latitudinal comparisons between the geology and biology of canyons from off the North Carolina coast to those extending northward to the Canadian border.