By Liz Baird, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Chief of School and Lifelong Education

August 25, 2016

Shelby launches an expendable bathythermograph (XBT), which measures the temperature of the water column down to 760 meters. Temperature and salinity measurements are used to calculate the water column sound velocity for more accurate mapping operations. Image courtesy of the Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 4 MB).

Have you ever wondered how people become scientists? Have you ever wondered if you could work on a research vessel? Or study the ocean? Or find a new species?

We provide some background information about the science team on the Explorers page. However, we want to give a sense of who these explorers were before they were scientists. Stay tuned to the Mission Logs page as we feature members of the science team throughout the expedition. First up is Shelby Bowden, multibeam processor.

Shelby in armor while on an educational field trip to Jamestown, Virginia. Image courtesy of the Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 267 KB).

Shelby grew up in the small town of Easley, South Carolina, primarily known for having “The Walmart,” but better known for being close to Greenville. His parents didn’t believe in video games or computers for kids, so he spent most of his time playing in the woods or creek beside his house and in the nearby mountains. His family regularly hiked and camped along the Blue Ridge and foothills, including his favorite trails near Matthews Creek and Rough Butt Knob. He loved to pick up rocks and sticks along the way, often conveniently convincing his parents to carry them in their backpacks because his would get too heavy.

Shelby’s mom worked as a zoologist before going to optometry school. Additionally, she homeschooled Shelby and his siblings until they reached high-school age and her background and proximity to both the mountains and ocean gave them lots of opportunities for field trips. During these outings, they studied plants and animals, history and science, math and English, and, of course, rocks, providing him with an integrated, multidisciplinary learning experience.

Shelby got his scuba certification when he was 10 years old. He was inspired by his sisters and father who were already certified. Image courtesy of the Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 119 KB).

When it came time to go to college, Shelby chose the College of Charleston because, “It was the furthest away from Easley I could get, and still get in-state tuition.” He was also interested in history, which was another draw to Charleston. He took a wide variety of electives, ranging from anthropology to calculus.

Reflecting on his love of rocks and the outdoors as a child, he chose to take Environmental Geology with Professor Robin Humphreys. His somewhat unexpected enjoyment of the course convinced him to sign up for more classes in geology, including Marine Geology with Dr. Leslie Sautter. There he found his passion. As he says, “Geology ties together so many different things. You can’t have geology without having biology, and chemistry, and physics. And you get to be outside.”

What Shelby thought of as “play” as a child turned out to be something he could do for class. Being out in the field was the biggest appeal, and he loved the field trips—even being “chest deep in pluff mud for the day.” Pluff mud is common in South Carolina; gooey, sticky, tar-like mud that appears to be solid. However, when you step in it, you sink and have to be very creative and persistent to get out on your own. “When you are walking around in pluff mud you can feel the objects hidden below, such as shells, old floats, or trash. Walking through the mud and finding these items makes it easy to comprehend how fossils and rocks could be formed. You can understand how something could be trapped in this anoxic condition, and over time with heat and pressure become fossilized or lithified,” says Shelby.

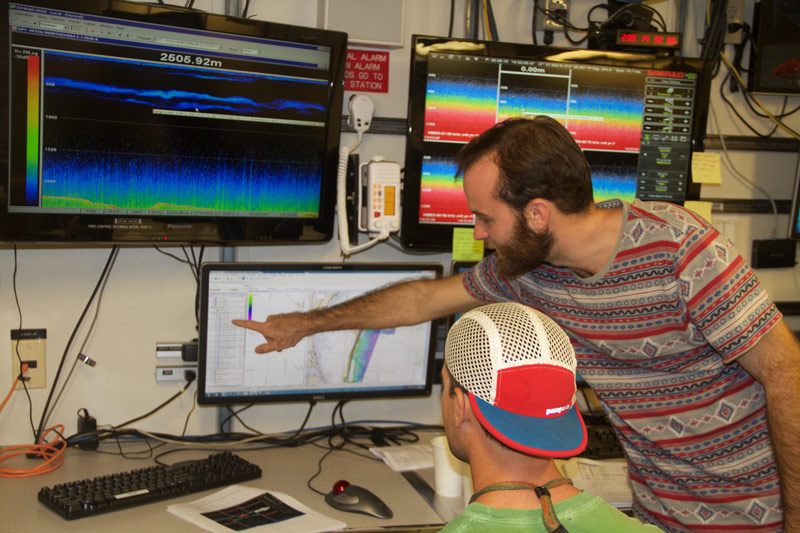

Shelby, aboard NOAA Ship Pisces, using existing multibeam data to create a map for the Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Image courtesy of the Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 7.3 MB).

Field experiences included trips to the beach to understand coastal processes and to the College of Charleston-owned property, the Dixie Plantation, to study water chemistry. He also participated in a month-long geology class in the western United States, where he camped, hiked, and developed geological maps. Being out in the field did not feel like being in class. To Shelby, the study of geology was engaging because there are so many unknowns. Classes were discussions, where he was encouraged to ask questions and felt welcome to voice his own theories. His face lights up when he talks about his professors and their ability to inspire students.

In the future, Shelby hopes to pursue a PhD in Geosciences. His challenge is trying to narrow down his area of interest. The multidisciplinary approach to learning provided by his mom spurs his interest today. Be it island arc volcano formation or seafloor structural analysis or barrier island erosion, he is interested in how all the pieces fit together.

When asked what advice he would give someone who wants to work in marine geology, he said to “take math and physics—even if you don’t want to.” Shelby has taken advantage of opportunities to participate in activities beyond the classroom, spending time on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer mapping the Marianas Subduction Zone (the deepest known area on Earth), assisting in DNR hydrology studies of construction-related effects on tidal creeks, spending days on the beach making elevation profiles, and working with eTrac Inc. on hydrography surveys.

He sees a future “working outside, with geology,” he laughed ironically, because he had spent most of the day inside on NOAA Ship Pisces, working on maps for this mission.