By Dann Blackwood, U.S. Geological Survey, Tarr Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park, AK

March 26, 2016

Some of the most interesting parts of the animals we collect can't be seen until we get them on the ship, manipulate them in ways that we can't while underwater, and photograph them with a macro lens designed to capture small details. Here, the underside of a “fuzzy” nudibranch is photographed in Dann Blackwood's photography tank. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 8.3 MB).

Today, Jeff Godfrey and I dove to 100 feet looking for Primnoa pacifica or the red tree coral in Tarr Inlet, near the Margerie Glacier. I was handed the camera after I backrolled into the water from the inflatable boat that we use to access the dive site from the research vessel Norseman II.

After signaling to Jeff that I was okay and ready to begin the dive, we let the air out of our dry suits and Buoyancy Compensator Device (BCD) and started our descent. There was poor visibility for the first 10 feet, with shimmery freshwater from the glacier that doesn't mix well with the saltwater. This effect makes things look out of focus and eerie. As we descended, we saw that we were next to an overhanging rock face covered with mussels and small ledges covered with a fine layer of silt. It started to get darker, so I was glad for the lights on my camera and the spotlight strapped to Jeff's hand.

The topside views in Glacier Bay National Park have been almost as exciting as the underwater seascape. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 7.2 MB).

The fractured rock face had many sea urchins, tube worms, and some sea squirts attached to it. As we swam by, the sea squirts and worms reacted to our presence and retracted. Shortly after, we saw a mass of urchins in a cluster; we're not sure what they were doing. The sea anemones on the seafloor were beautiful shades of yellow and red, and some were bigger than my head. As we moved around the site, we tried to not disturb the silt on the rocks because it clouds the water and makes it hard to see the rocks and each other. Our dive lights are really helpful for staying together.

Jeff was a few feet below me and suddenly I saw the coral that we were searching for! It was growing on a little outcrop of rock and was pinkish in color and looked pretty healthy. I signaled Jeff to take a small sample for analysis and he placed the sample in his sample bag along with a couple of sea squirts that he had collected. As we sampled the coral, we noticed a beautiful shrimp swimming around and landing on it. Later, we encountered some sponges that were partly dead and some that were healthy. Even the dead parts supply habitat to many organisms, including polychaetes, shrimp, and other small crustaceans. As I proceeded along the wall, I found a flat shell that was attached to the rock about the size of my fist. Jeff gently pried it off and put it in the sample bag for us to identify once we are back on the ship. It appeared to be some type of jingle shell, but this one was much bigger than any I have ever seen.

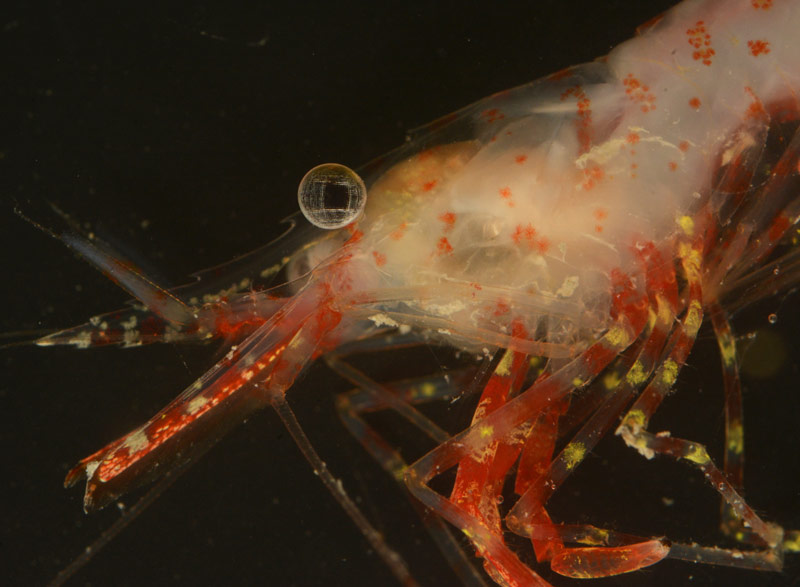

Interesting details, like the complex pattern in this shrimp's eye, are difficult to see until you bring the sample back to the lab. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 8.7 MB).

As we started to feel the cold in our hands, we knew our time to ascend was near. We checked our dive computers and slowly made our way up the wall. The surface was a beautiful emerald green with our bubbles trickling upward toward the light. We took our time and paused at 15 feet for a safety stop to help our bodies get rid of the excess nitrogen that was in our bloodstream. After we surfaced, we signaled to our dive tenders in the inflatable boat who quickly helped us get our SCUBA gear into the boat. It was a very successful dive.

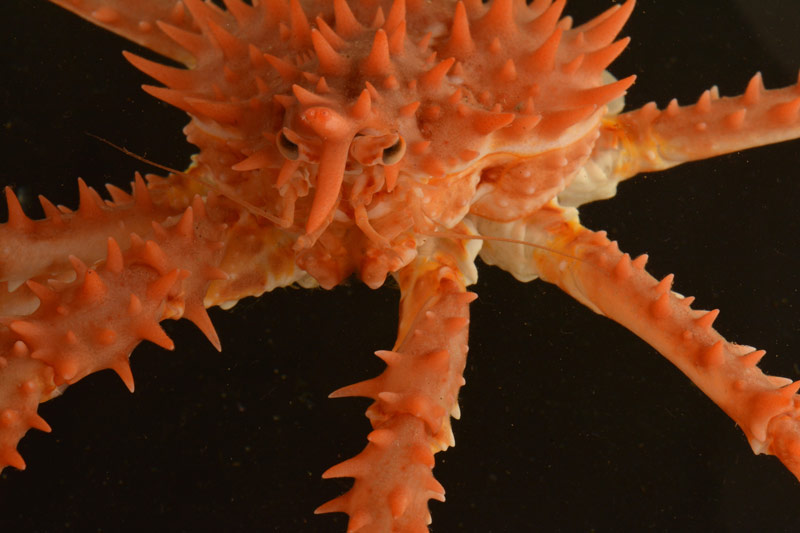

This juvenile king crab, or perhaps we should call him a “prince crab,” was found during our dive near Tarr Inlet. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 9.3 MB).

Once I was back on the Norseman II, looking at the video of our dive, I realized how much scientific investigation depends on the use of photography and other types of imaging. I have been using a translucent plastic tank and two flash units set up on each side of the tank to capture images of the organisms that we bring up with the remotely operated vehicle and during SCUBA dives. It is always fascinating to see the ocean's creatures up close and to admire their structure and beauty in a way that isn't possible during the dives.

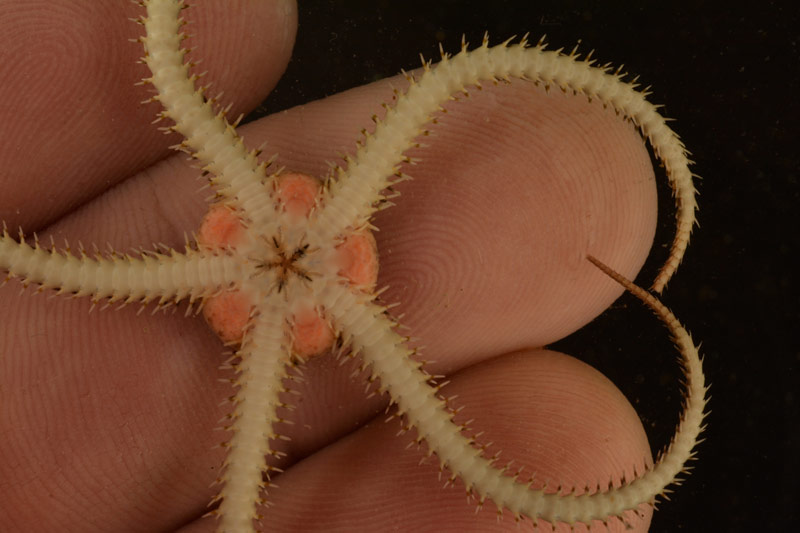

Once a sample is back on deck, we are able to see very small details, like you can see here on this small brittle star that we never would have been able to see on the remotely operated vehicle footage. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 8.9 MB).

Before photography, samples were collected and preserved and then dried and described, most were drawn with pen and ink. This process was slow and prone to error and it was difficult to show the samples in all their dimensions. With the tools of photography and video imaging, science can proceed more accurately to document the Earth's processes, its creatures, its changes, and even things unseen by human eyes. I really love diving and using imaging to help the process of scientific discovery and show others our blue watery world.