By Caitlin Adams, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Web Coordinator

September 14, 2017

Amanda Demopoulos watches as deck crew members Knott and Cornell deploy the CTD at Pea Island B. The CTD collects conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth (pressure) data, plus it has sensors to detect dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll, and turbidity (particles in the water), as the instrument travels down to the seafloor. The CTD is also equipped with a rosette of Niskin bottles, which are specially designed water bottles that can be triggered to collect water at set depths. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 3.4 MB).

With a day lost for weather at the beginning of the cruise and Hurricane Jose still a potential threat offshore, the DEEP SEARCH team is working as efficiently as we can to accomplish our mission. Chief Scientist Amanda Demopoulos is in near-constant contact with the Pisces Operations Officer, LT Jamie Park; the two work together to plan and re-plan the order and timing of operations to maximize the utilization of our days at sea.

On a cruise like this, there are many operational considerations to weigh as plans are made. There’s the obvious factor of weather: open ocean conditions can change rapidly, and the ship is always monitoring multiple forecasts to ensure that science operations are possible and, more importantly, that everyone aboard stays safe. There’s the factor of time, too: each type of operation (Sentry dive, CTD deployment with monocore, shipboard multibeam mapping) we want to complete takes time, and Amanda and Jamie have to figure out the best sequence of events.

More importantly, each of these operations can’t be completed solely by scientists—the ship’s crew plays an integral role in all of these tasks, and we have to be sure to schedule around their needs as well. While we scientists may only be out here for 17 days, crew members are here nearly year-round, and we must be respectful of both their other duties on board as well as their free time. We try to schedule everything during daylight hours so that the crew doesn’t work outside their scheduled hours, especially because even with planning, they’re often needed to complete unscheduled tasks (like today, when they managed to re-terminate a failing CTD cable in the short transit between sites). The only exception to this is Sentry diving: while we schedule every launch and recovery during daylight hours, Sentry is fine to stay in the water overnight with the ship closely following it—after all, someone is always on the bridge driving the ship.

After the CTD has been recovered, Jason Chaytor attaches a tube to each Niskin bottle and transfers the water into plastic jugs, which will be brought into the lab and filtered. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 4.4 MB).

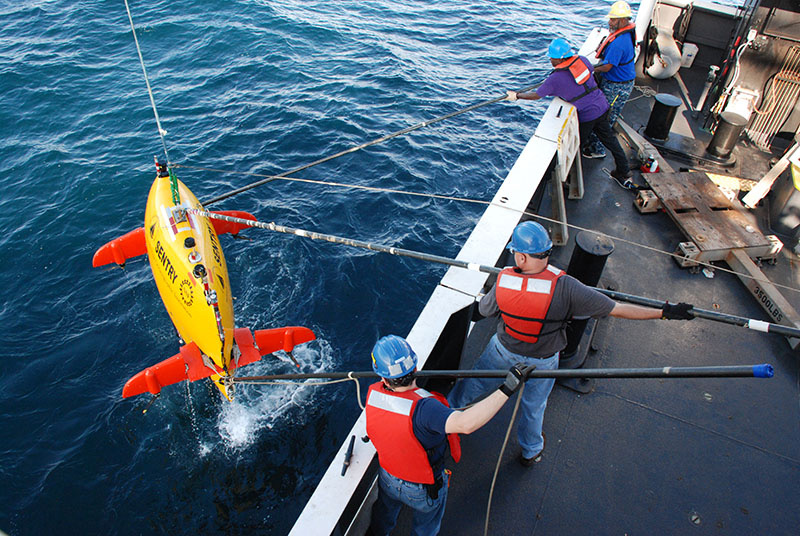

Sentry expedition leader Sean Kelley remotely drives the AUV toward the ship after surfacing. Once within range, it will be connected to the ship’s crane and lifted back on board. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 5.5 MB).

Finally, there is one other important factor to consider: location. Though we arrived at the ship with a detailed cruise plan in hand, many of those plans, including our order of sampling sites, have had to change. Because we started the expedition in Norfolk, Virginia, instead of Morehead City, North Carolina, we started at one of our most northern sites, the Kitty Hawk bubble plume seep sites (site 12). From there, we are working our way south, adjusting as needed.

A couple of our sites are too shallow for Sentry to dive and maintain communication with the ship, and a couple others may fall off the priority list given time constraints. Each day, we have to consider which sites make the most sense given all we want to accomplish once on station and how long it will take to transit between locations.

Sentry engineers (bottom, Ian Vaughn and Andy Billings) and the ship’s deck crew (GVA Fountain and CB Walker) work to secure tag lines on the vehicle. Once secured, these lines help them to steadily guide the Sentry onto the deck and into its cradle. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 6 MB).

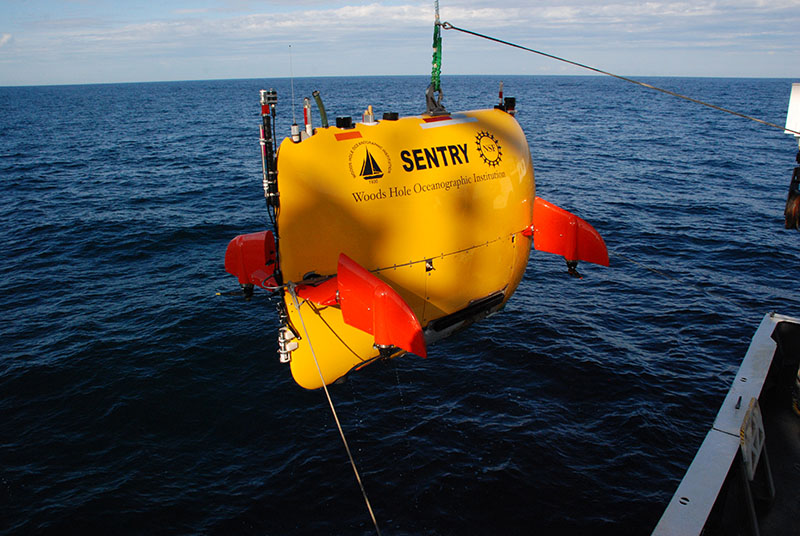

The ship’s crane operator slowly moves the Sentry over the side and back onto the deck. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 5.2 MB).

So with all of these factors to weigh, what exactly do we get done in a day? Quite a lot, actually! Today was our busiest day yet, and here’s an idea of how it went:

In the coming days, we’ll be sharing more about how and why we collect the Sentry, mapping, water, and mud data that we do, and you’ll get the chance to hear directly from a few of the scientists we have with us on the mission.