By Sandra Brooke, Florida State University

August 18, 2017

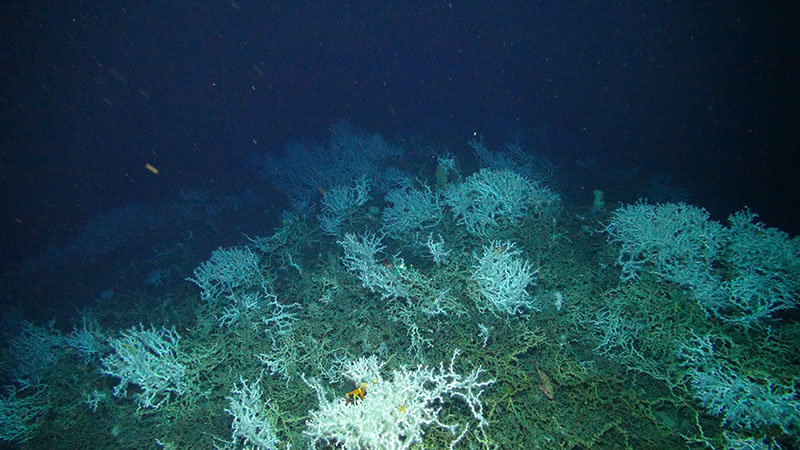

Thickets of living and dead Lophelia pertusa colonies at Many Mounds on the West Florida slope at 500 meters depth. Image courtesy of NOAA Southeast Deep Coral Initiative and Pelagic Research Services. Download larger version (jpg, 9.6 MB).

Ever wondered how corals make babies? Probably not, but here it is anyway! Corals can reproduce in a number of ways: colonies can be all male or all female, they can be hermaphroditic with males and females in the same colony, they can release eggs and sperm directly into the water, or they can brood larvae that swim or crawl to a nearby home when ready to settle and grow. As adults, all deep-sea reef-building stony corals, such as Lophelia pertusa, are either male or female colonies that broadcast spawn. Tiny coral larvae then drift and swim for weeks before probing the seafloor in search of the right conditions to start a new colony.

Initially, researchers assumed that conditions in the deep sea were uniform, lacking the seasonal signals (e.g., temperature, light) that influence shallow-water species. Scientists also thought that without seasonal signals, deep-sea animals would breed slowly, but continuously. As it turns out, the deep sea can be quite dynamic and many species, including all the reef-building corals, have annual cycles of reproduction that end in a dramatic spawning event that has yet to be observed.

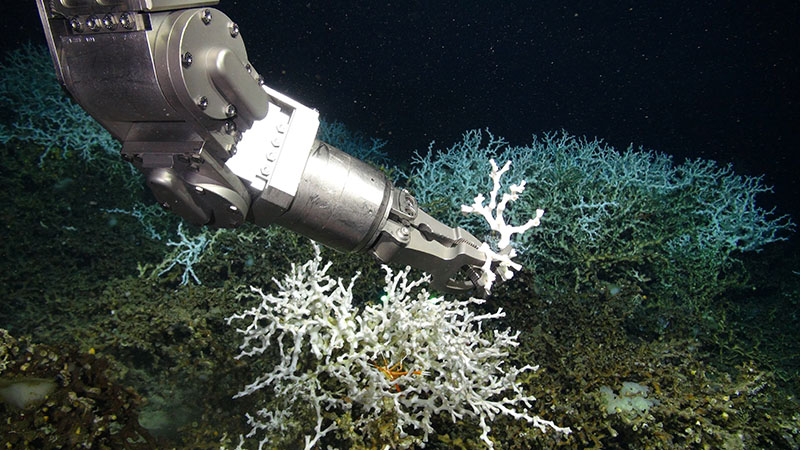

The robotic arm of remotely operated vehicle Odysseus sampling a small fragment of Lophelia pertusa on the West Florida slope. Image courtesy of NOAA Southeast Deep Coral Initiative and Pelagic Research Services. Download larger version (jpg, 8.5 MB).

Corals don’t move, they are cemented to the seafloor. The only way these animals can colonize new areas is by sending their larvae away into the current. The tiny larvae settle, grow, and begin a whole new reef that can eventually source larvae to even more new sites. This process can take decades, as deep-sea corals grow only a centimeter or two per year, but it is essential for maintaining genetic diversity, connecting populations, and ensuring long-term survival of the species.

Sandra Brooke, Associate Research Faculty at Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Lab, admiring coral samples collected by remotely operated vehicle Odysseus from NOAA Ship Nancy Foster. Image courtesy of Peter Etnoyer, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. Download larger version (jpg, 2.8 MB).

Fragments of Lophelia pertusa, including a rare orange color variety, collected on the August 2017 Southeast Deep Coral Initiative expedition. Live fragments are maintained in a chilled tank during the cruise and will be packed in smaller containers for transit to Florida State University’s Marine Lab. Image courtesy of Heather Coleman, NOAA Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program. Download larger version (jpg, 5.2 MB).

During this expedition, we collected small pieces of Lophelia from several different colonies in different locations. Parts of each fragment have been preserved to assess the maturity of its eggs and sperm, which will provide information on the timing of spawning events. Other parts of collected Lophelia are living in a chilled tank on the deck of NOAA Ship Nancy Foster until we reach shore and they can be transferred to Florida State University’s Marine Lab. The coral will be maintained in cold water systems to be spawned, which we hope will provide larvae to study.

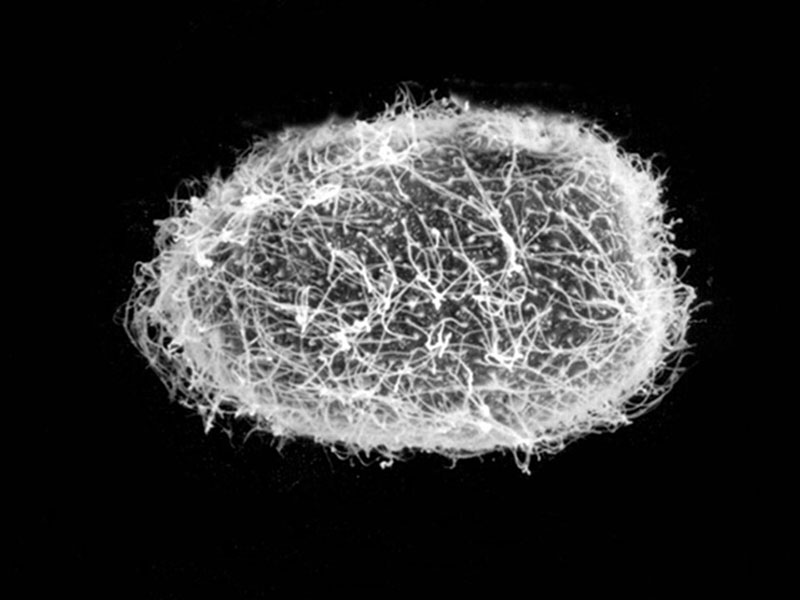

A few years ago, we successfully gathered larvae from Norwegian Lophelia, where we learned for the first time how their larvae develop and how long they can live. While this research has provided valuable information, there is still lots more to learn. For example, understanding how temperature and other environmental factors affect larval survival and lifespan will allow us to predict how future ocean conditions might affect the distribution of this critical habitat-forming species, as well as the fish and invertebrates that call these reefs home.

Scanning electron microscope image of a deep-sea coral larva approximately 0.15 millimeters long with hundreds of hair-like cilia that the larva uses to swim. Image courtesy of S. Brooke, Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 132 KB).

The expedition is supported by NOAA’s Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program through the Southeast Deep Coral Initiative (SEDCI), a multi-disciplinary effort that will study deep-sea coral ecosystems across the Southeast United States in 2016-2019.