By Lisa Levin, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

October 29, 2020

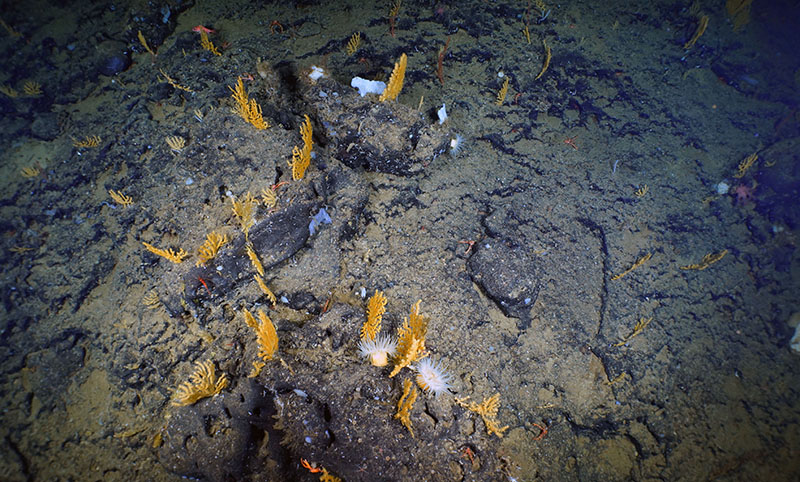

A deep-water coral garden composed of Acanthogorgia sp. sea fans and mushroom corals (Heteropolypus sp.) was identified on the flanks of San Juan Seamount at 880 meters (~2,624 feet). Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust - Cruise NA124. Download larger version (jpg, 3.5 MB).

People are curious by nature and drawn to frontier settings. Marco Polo, Davey Crockett, Ernest Shackleton, Jacques Cousteau, and Captain James Kirk are all testimony to the human desire to “go where no man has gone before.” This desire is no different in regards to the deep sea, a place of mystery and isolation. It is, with good reason, often referred to as "inner space."

We are naturally drawn to the strange and wonderful creatures of the deep sea, and can now view them in ways never before possible thanks to remarkable close-up, zoomed-in cameras and telepresence beaming the images to our home computers. Despite this curiosity and technological advances, we still have not seen most of the animals or sampled most of the microbes in the deep ocean. We often don’t know where animals live, what they eat, how they reproduce, and what role they play in greater ocean processes like carbon cycling.

Why might we want to know these things? I would argue that curiosity about the natural world could be most important. But often there are more applied motivations driving ocean exploration and scientific study. The growing human population has led to greater demand for food, energy, pharmaceuticals, and minerals. As we deplete these resources on land, we have sought them in the ocean, and, in recent decades, in the deep ocean.

Along the central Patton Ridge, brisingid sea stars, anemones, and sponges were observed to occur in high densities on steep, iron-manganese encrusted rocky faces. Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust - Cruise NA124. Download larger version (jpg, 4 MB).

The continued discovery of novel biodiversity in the deep ocean is often accompanied by discovery of new resources – the push to use these resources is termed the ‘blue economy.’ Technology has enabled us to fish deeper, drill for oil and gas deeper, discover new marine genetic resources, and probe for deep seabed minerals. Although there is no place we cannot reach, when we extract resources without careful study, we run the risk of damaging or destroying life before we have discovered it.

The deep sea has the potential to offer us new sources of food, cures for diseases, climate solutions (e.g., enzymes that can remove carbon dioxide), novel sources of energy, and more. But we need to find a way to take advantage of this potential without disrupting the important services that the ocean provides – absorption of carbon and heat from the atmosphere, productivity, and fisheries. To be responsible caretakers of our planet, we need to understand what lives in the deep ocean and how deep-sea ecosystems function.

The research planned for this expedition to mineral-rich settings in the deep waters off southern California is a small step on this road to deep ocean sustainability. We hope to learn what animals and microbes live on or avoid phosphorites and iron-manganese (Fe-Mn) crusts that form on the banks, seamounts, and ridges under low oxygen waters at depths of 400-1,500 meters (1,312-4,921 feet).

Although deep seabed mining is not currently an issue in southern California, phosphorites are increasingly being targeted for fertilizer, and the Fe-Mn crusts for rare earth and other elements elsewhere in the world. Our studies of animal and microbial biodiversity associated with these resources should help inform society’s management and decision making in the deep ocean.