The Deep East Mission Patch represents the three target focuses during the September 2001 Voyage of Discovery.

Deep East Web Forum

From September 24-27 students in the classroom and members of the public interacted directly with scientists and explorers at sea on the Deep East Expedition by logging onto an Ocean Explorer Web forum and asking them questions using a text-based interface. All messages that were submitted were moderated to ensure that the comments and questions made public were appropriate for students, and individuals of all ages. In most cases questions posted to the Web forum during its four-day operation were answered the following day. Below is a list of the scientists and explorers that participated in this online forum and an abridged transcript of the forum.

Deep East Scientists and Explorers

Dr. Michael H Bothner: Geochemical Oceanographer at the U.S. Geological Survey

Dr. Bruce Brownawell: Biogeochemist at the State University of New York, Stony Brook

Dr. Scott France: Deep-sea biologist at the College of Charleston.

Andrew Shepard: Associate Director of the National Undersea Research Center (NURP) at the University of

North Carolina at Wilmington.

Mr. Joe Wargo: Program Analyst for NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration

Abridged Transcript of Web Forum

Naomi, Emily and Becky-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Are you ever afraid of what species might actually be down there?

Dr. Scott France: I have always been so excited to see what is on the ocean floor that it has never crossed my mind to be afraid of the species. Are you wondering about the possibility of some giant sea creatures? A couple of years ago, a group of scientists used a submersible near New Zealand to search for a giant squid. They weren't afraid, but rather excited at the possibility of seeing this creature alive.

Nick-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Is it cold in the submersible?

Dr. Scott France: It can get very cold in the submersible. When the sub is on the deck of the ship, the temperature inside is the same as the air temperature outside. So it can be very hot. But when the sub dives down below 1000 meters, the water temperature can get below 2 degrees Celsius. Since the sphere of the sub is metal, it cools down very quickly and the air temperature inside the sub drops as well. During a long dive, the temperature can get cold enough that people in the sub put on sweaters, hats, mittens, woolen socks, etc. During my dive on Sept. 10, the computers in the sub generated enough heat that it didn't get too cold, and I felt comfortable in my shorts and a long-sleeved shirt. But in the past on deeper, longer dives, I've had on lots of layers of clothes and still shivered!

Maggie-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: How many people are usually on the Atlantis at one time? The Alvin?

Dr. Scott France: The Atlantis has space for 23 crew members (who conduct the operations of the ship), 13 technicians (who maintain and run Alvin and the ROVs), and 24 scientists. On the first leg of the Deep East cruise, there were a total of 49 people on board the Atlantis. The Alvin submersible can hold three people, usually a pilot and two observers. The observers are usually scientists.

Kathleen, Alex and Ashley-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Do you ever have second thoughts or fear for your life before getting ready to explore the deep ocean? Also, are you ever afraid that the Alvin or whichever sumersible might cave in over you under the pressure of the ocean? Do you ever get nervous about the possiblity of getting nitrogen bubbles in your blood? Have you ever had nitrogen bubbles in your blood system?

These specially designed traps isolate the shrimps and crabs inside from light and elevated water temperatures as they are brought to the surface. Click image for larger view.

Dr. Scott France: On the first several dives I took, I was so excited to finally get a chance to see the deep sea with my own eyes, that I did not have a second thought to the potential dangers of being in a submersible. But since that time, I have to admit that I have on occasion spent a little more time considering the potential dangers. Still, even though I may have had "second thoughts," they have never prevented me from diving in the submersible when the opportunity was available. I trust the Alvin crew and technicians, who spend long hours checking and rechecking all of the systems on the sub, to have Alvin in tip-top shape. I've never worried in particular about the sub caving in because of its design. The round shape of the sphere provides support against the water pressure from all directions. Your last two questions refer to the painful condition known as the "bends." The appearance of nitrogen bubbles in the blood is caused by a rapid change from high pressure to low pressure. Although the exterior of the sub is exposed to high pressure in the deep sea, the sphere is sealed by a hatch on the surface, and so the pressure inside the sub does not change during the dive. Thus there is no danger of nitrogen bubbles appearing in the blood of anyone inside the Alvin.

Andrew Shepard: Safety is always a big concern at sea. One of the most dangerous jobs is offshore fishing. We do a lot of planning and strive to use the best equipment and people to ensure that things go right. Still, there will always be some risk, but we feel it is no more than other jobs that take us to unknown areas. Alvin has a titanium sphere 4 inches thick and its acrylic viewports are 3.5 inches thick. It can dive to 4,500 meters but has a safety margin on top of this depth. The sub crew also plans dives to ensure that the bottom under the sub is always less than 4,500 meters.

(top)

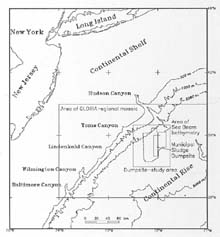

Map showing Deep Water Dumpsite 106 (DWD-106), where sewage sludge has been dumped for decades. Click image for larger view.

Laura-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: What do you think of ocean dumping?

Dr. Bruce Brownawell: Ocean dumping can involve a wide range of activities including: disposal of sewage sludge, as was done during the late 1980's and early 1990's at the 106 Mile Site; disposal of harbor sediments that need to be dredged for navigation; and disposal of hazardous wastes, including low or high level radioactivity. There are no perfectly safe disposal options for any of these materials and the arguments depend greatly on the material to be dumped. With respect to sewage sludge, it can either be landfilled, used as organic fertilizer (the fastest growing use), incinerated, dumped at sea, or shot into space. My personal view is that the two best options from an environmental perspective are carefully controlled ocean dumping and incineration. The first option is presently illegal in the U.S., and the second option is rarely implemented because of local opposition. One of the "hot topics" in environmental quality research right now is how to best manage and assess the risk of using composted sludge in agriculture. Almost a third of our sewage sludge in the U.S. is now used for this purpose.

Ashley-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: What is one of the coolest things you have ever seen?

Dr. Scott France: One of the coolest things I have seen in the deep sea is a hydrothermal vent community. At the Rose Garden vent field, at a depth of 2,500 meters on the Galapagos Rift in the Pacific Ocean, I saw large clumps of brilliant red tube worms projecting from their white parchment tubes. Crawling over the tubes were limpets, shrimp, amphipods, and crabs, while squat lobsters hung around the periphery. At a vent in the western Pacific at 3,600 meters depth I saw hundreds and hundreds of beautiful white anemones on the black basalt bottom. We called this place "Anemone Heaven."

Andrew Shepard: Hard question, as every time I go into the deep sea, I see something new. The coolest thing I ever saw on a submersible dive was in Oceanographer Canyon off New England. We were stuck on the bottom in the canyon in a strong current, waiting for the current to slack off. A giant bluefin tuna rammed its nose into the sub's sphere about a foot from my nose. It then circled us for five minutes before we left. It turns out that this giant tuna did the same thing to a sub in the same place the year before. Perhaps the tuna was protecting its territory and thought we were another tuna?

Thousands of lanternfish gather outside the Alvin during a dive into Hudson Canyon. Click image for larger view.

Julian-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Do you consider your job fun, or all work, no fun?

Dr. Scott France: FUN!! How many people get to travel to many interesting places around the world, dive to the bottom of the ocean in terribly cool submersibles, and discover brand new forms of life for their job? And then I get to share my excitement with students, and it is a lot of fun to see you get excited. Make no mistake that there is a lot of hard work involved (and many years of school before you get to this point), but the rewards are great

Andrew Shepard: The best advice anyone can get who has to go to work for a living, is to find a job and work that is fun for you. There are always days in any job that aren't fun (like when I have to go back to the shore and do my travel paperwork). But, I would say that a job in marine science is fun work, and allows us to feel as though we are making a contribution to the health of the Earth and future generations.

Alex-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: What made you decide to become an Ocean Explorer? What did you have to do to become one? What would you say is your favorite part of your job? Your least favorite part?

Andrew Shepard: I love to be on, or better yet, under the water. To be a scientist, education through college is a must. There are other jobs on the ocean that do not require an advanced degree. However, to get any job you really want, you must show initiative and dedication by taking every opportunity to get experience. Most favorite—riding a submersible or scuba diving to a new, unknown place. Least favorite— we have to do alot of reading, and at times, I would rather be outside.

(top)

Kyle-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: How long is the average dive in the Alvin?

Dr. Scott France: Most dives last between 6 to 8 hours. The length of time depends on the battery power. If a lot of power is being used while on the bottom, for example, because you are constantly using the exterior spotlights so you can run video transects, then the dive will be shorter because the batteries are drained more quickly.

Scott-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Did you find any new species?

Dr. Scott France: We won't know the answer to this question until we bring the specimens back to our labs and do a complete study of them.

Tom-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: How much money do you make?

Dr. Scott France: Instead of specifics, let me tell you about the range of salaries you might expect if you were a marine biologist. The answer depends on how much education you have and the sort of position you currently hold, e.g., academic vs. government vs. industry. The salary may range from a low of about $25,000 (for a technician without an advanced degree) to about $150,000 (for a tenured professor at a large research university).

Images taken from Alvin as it ascends the steep west wall of Oceanographer Canyon, note the distribution of corals near the lip of the terraces. Click image to see a video.

Hazel: What would be the main difference between a dive in the 'Deep East Voyage of Discovery' and a dive in the Pacific Ocean? Would the Deep East be colder? Do you always see deep thermal vents and tube worms?

Dr. Scott France: The differences would depend on the type of bottom in the area of the dive, regardless of ocean. For example, on leg one of the Deep East mission we dove in Oceanographer Canyon, which had exposed rocky outcrops and ledges, and saw many species of corals and sponges. The next dive, into Hydrographer Canyon, revealed a mud-covered bottom and no corals, but many soft-bottom organisms, including worms and urchins. Water temperatures in the deep sea depend mainly on depth and not geographic location. For example, at 3000 meters depth, it is less than 2 degrees Celsius at the equator, at the poles, and in between, in both the Atlantic and the Pacific. Deep hydrothermal vents are restricted to areas in the deep sea where the Earth's interior molten rock underlies thin spots in the seafloor crust, such as at mid-ocean spreading centers. In these areas, water is heated by the molten magma. Hydrothermal vents make up only a very small area of the deep-sea floor; most of the deep sea bottom is covered by mud.

Georgie-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Does it ever get hard to breathe in the Alvin when you are on a dive or mission because the Alvin is so small? Also do you think the Alvin is too small for 3 people to fit?

Dr. Scott France: The Alvin is equipped with oxygen tanks, which constantly add oxygen into the sub, and CO2 scrubbers, which remove carbon dioxide from the sub. So there is no problem breathing over the course of a dive. There is approximately 6 square feet of floor space for the 3 passengers in Alvin, which is a fairly cramped space. After 7 hours or so there is no question that we'd all like to stretch our limbs, stand up and walk around! But I would not say the sub is too small, and, given that for more than 30 years scientists have eagerly jumped at the opportunity to squeeze into this small space for a glimpse of the deep sea, I'd say most folks would agree with me.

This orange gas hydrate is home to Hesiocaeca methanicola, a newly discovered species of marine worm found in the Gulf of Mexico in 1997. Click image for larger view.

Angela and Karen-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: If you have spare time while you're in the Alvin and the Atlantis, what do you do?

Dr. Scott France: If I have spare time in the Alvin I spend it looking out of the port hole. I never know if I'll ever have another opportunity to visit the deep sea, and so I relish the view for as long as I can get it. I even watch out the port hole as the sub descends and rises to and from the sea floor, enjoying the bioluminescence flashing in the inky blackness of the water column. If people have spare time on the Atlantis, they may spend it watching movies in the lounge, reading in the library, exercising on some of the fitness equipment, or even playing ping pong in the main science lab. As you can tell, the Atlantis is well outfitted for her long voyages.

Alex-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Does it seem like time passes more slowly while you are underwater? Faster?

Dr. Scott France: For me, the dive is always over too quickly! So I'd say time seems to pass faster.

(top)

Amanda-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: How many people could you fit in the Alvin? Has the Alvin discovered any new species?

Dr. Scott France: The Alvin is a 3-person sub. Scientists making collections of deep-sea organisms using Alvin have brought back many, many new species.

Laura: What part of going down into the ocean do you think is the best and worst? Has anyone been in any other submersible?

Alvin collects a suction sample using one of its robotic arms. Scientists are investigating invertebrates that live on deep water corals, such as this Thourella sp. Click image to see a video of Alvin sampling.

Dr. Scott France: The best—seeing organisms that you can see nowhere else on Earth. The worst—that the time we can stay submerged is so short. There are several other research submersibles in operation. If you look at the Ocean Explorers web page for the Islands in the Stream cruise, you will see they are using the Johnson Sea Link submersible. I have had several dives in the Pisces V, a submersible operated by the National Undersea Research Lab in Hawaii. Like the Alvin, the Pisces V is a 3-person submersible with two manipulator arms, although the interior is slightly different (for example there are "benches" for the observers to lie on to look through portholes) and it can dive to "only" 2000 meters depth (vs. 4500 meters for Alvin).

Zac-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Does it ever get so cold that the computers freeze and don't work?

Mr. Joe Wargo: No, not that cold, but it does get chilly inside Alvin as the sub descends into the darkness. Not freezing cold, but the pilot and scientists who use Alvin all take sweaters or sweatshirts to stay warm!

Andrew-Medford Memorial School, New Jersey: Does the underwater current carry the sub or make it more difficult to operate?

Mr. Joe Wargo: The currents do have an impact on the sub, but nothing that we can't handle. Sometimes a strong current will cause the sub to land a little bit away from the desired point, and the current can cause the sub to move forward slower than desired.

Phil: Have there been any problems with the Alvin or Atlantis? What were they?

Rough seas caused the cancellation of dives for Alvin during several days of the Deep East Expedition. Click image for larger view.

Mr. Joe Wargo: If you're talking about the Deep East Voyage, there have been no serious mechanical problems with either Alvin or Atlantis. Our only problem was with the weather.

Alicia-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: How long have you been preparing for one of the dives on the Alvin? What are some of the last minute checks that you do if there are any?

Mr. Joe Wargo: I read this as two issues: How long/what does it take to become an Alvin pilot, and what pre-dive checks are required. To be an Alvin pilot requires extensive on-the-job training that varies in length by individual. "Pilots" are not hired specifically for that purpose. Generally, persons with mechanical or electrical engineering degrees are hired to perform other duties, and later express an interest in learning to be pilots. A pilot-in-training is required to know all about all of the systems onboard Alvin, which requires a lot of studying. It's not for everybody, and takes a very special person who is smart, dedicated and willing to work very hard. Last minute checks are very extensive. Pre-dive checklists are required by five different people: the pilot, surface controller, expedition leader, support ship Master and the chief scientist. Safety is paramount. As a result, nobody has been lost or seriously injured in over 3,700 Alvin dives.

Joshua-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Would you ever be afraid or frightened to have any kind of living organisim or really anything getting sucked up into the engine? Also would you worry about anything hitting the Alvin to knock it off course?

Mr. Joe Wargo: Not problems. The engines are safely located inside Alvin.

(top)

Sam-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: How do you get your air in the Alvin? How long can you stay underwater before you have to go back for air?

Mr. Joe Wargo: Alvin carries its own air. Carbon dioxide, created by the pilot and passengers, is cleaned from the air, and fresh air supplied automatically. However, there are limits. Normal operation of Alvin is 6-10 hours depending upon how much power the sub uses to operate all of its systems. In an emergency, Alvin can support life for up to 72 hours. So far, it has never had to do that. Normally, air is made up of 21 percent oxygen. After the dive yesterday, air in Alvin was 17 percent oxygen after 8 hours.

Jeff-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Have you ever discovered any ships or air craft carriers on any of your expeditions.

Alvin collected this ft-long (27 cm) chemosynthetic mussel, Bathymodiolus, on the Blake Ridge . Click image for larger view.

Mr. Joe Wargo: In Alvin, not that I am aware of. She is not built for that purpose. Look at the story of the Thunder Bay Expedition on our website for a good example of shipwrecks!

Josh-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: What organism did you see most recently? Describe it for me.

Mr. Joe Wargo: Yesterday, we found the biggest mussel I have ever seen - it was over a foot long, and you can read more about its discovery in the web log for Sept. 25th.

Becky-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Have you ever thought about posting live video of the dive in the Alvin so we could see the animals, creatures and coral on the Internet?

Mr. Joe Wargo: I'm afraid video clips are the best we can do today. Even on Atlantis, we do not have access to video until Alvin comes to the surface. Given the technology available, the cost would be prohibitive. Maybe some day in the future...!

For video clips, check out the logs for Sept 11, Sept 22 and Sept 27. Also, if you follow the links to the "Gallery" on the Ocean Explorers page, you'll find lots of images of the animals seen on the various cruises under the "Living Ocean" link.

Debbie-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: Have you discovered any new species on this voyage?

Dr. Scott France: We won't know the answer to this question for sure until we bring the specimens back to our labs and do a complete study of them. However, it is very likely that there will be new species among the organisms found at the methane seeps being sampled right now.

Nick-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Did you see any squid, sharks or blue whales?

Dr. Scott France: On leg one, we saw many squid and sharks. You can see a photo of one of the squid on the Sept. 11 log. Black dogfish, a type of shark, were very abundant in Oceanographer Canyon. We saw no whales.

Susan-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: Have you ever come across something you could not classify?

This unusual deep-sea medusa (jellyfish) was observed in Hydrographer Canyon. Click image for larger view.

Dr. Scott France: When we are in the sub, there have been several occasions when we have been uncertain of the type of organism we are seeing. Usually, if we collect the organism we can classify it when we look at it on the ship. However, I can think of a couple of occasions when it took much longer to figure out what kind of organism was collected. When biologists first visited the Galapagos hydrothermal vents with Alvin, they weren't sure how to classify the "dandelion animals." Later they discovered they were siphonophores, which are related to jellyfish.

Ronald-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: What is the temperature at 10,000 feet deep in the ocean?

Dr. Scott France: Below 1500 meters (about 5000 feet), the water temperature is typically less than 4 degrees Celsius.

Larissa-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: When you dove in the Georges Bank Canyons and the Bear Seamount, what did you find out about the coral?

Dr. Scott France: I was really surprised to find so many coral colonies in Oceanographer Canyon. We collected some coral tissue and will be studying it in our labs to learn about their reproduction and genetics.

(top)

Christine: What is the hardest thing to get used to when you are in the submersible?

Dr. Scott France: Probably that your vision is so limited. You'll see something swim by the porthole and you want to get a better look, but there are no other windows to look through!!

Michele-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: Recently, Hurricane Erin hit. Because of this, you were left with rough waters. What are some of the difficulties that could occur in the submersible due to rough waters?

Dr. Scott France: Once the sub is below the surface, it is very calm despite how large the waves are above. However, if there is rough water, it is difficult to hoist the sub back up onto Atlantis. As Alvin is pulled from the water, there is a short period of time when it swings on a rope, and if the sea is rough, there is a danger it could smack back hard into the water or collide with the back of the ship. For these reasons, the dive is cancelled if there are high seas.

Mallory-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: Why where you chosen for this expedition?

Dr. Scott France: Scientists must write a formal proposal to carry out research on Atlantis and other oceanographic vessels. These proposals are evaluated by other scientists and some are funded. So in this case, groups of scientists with particular research specialties asked to come to these areas to conduct studies. The Deep East Expedition combines the research projects of the funded scientists who were looking to conduct their research in the deep sea adjacent to the east coast of the U.S.

Josh-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: Who sponsored your dives and expeditions?

Dr. Scott France: The expedition is being funded by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration through their Ocean Exploration program.

Scott-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: What impact did the NY tragedies and the change in plans on your port stop in Manhatten have on your voyage?

Dr. Scott France: Like everyone else, we were horrified to learn of the attacks, and it was difficult to concentrate on our science. At the end of our leg, we were supposed to transfer at sea from Atlantis onto a smaller vessel which would take us in to New York City. Many of us had flights leaving from NYC or people meeting us there. When the magnitude of the tragedy was clear, the schedule was revised and we returned to Woods Hole. We had to reschedule flights, car rentals, lifts, etc., and the scientists getting on board for leg two had to get their equipment up to Woods Hole. The festivities that were planned to take place in Manhatten after leg two were also cancelled.

Warren-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: What is your schedule for a typical day on the Atlantis?

Benthic ecologists work late into the night seiving for small organisms found in Alvin's box-core samples of the ocean floor. Click image for larger view.

Dr. Scott France: Well, there is no "typical" day on Atlantis, because there are so many different types of people doing different things. Breakfast is from 0700 to 0815, and lunch and dinner are also scheduled at regular hours. However, ship operations or science activities do not always conform to regular hours. The cooks are nice enough to put meals aside for anyone who will be working and not able to make meals. This seems to be the norm rather than the exception. Almost everyone is on-hand to watch Alvin go to sea at 0800! This is usually followed by a meeting of all the remaining science party to discuss past and future dives. When Alvin returns from the bottom of the ocean, science happens! There is a flurry of activity as members of the science party begin to investigate and/or process samples collected! Scientists and their students often work on interesting samples into the wee hours of the morning. Last night for example, several were viewing video of the dive at 3 AM! It's nice to be involved with "work" that is so interesting, and so much fun!

Brian and Justine-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Do you use quadrats when you mark the ocean floor?

Mr. Joe Wargo: If you mean marking small areas for a complete sampling of everything that is located in that area, we are doing that at times during this voyage.

(top)

Anna-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Were you interested in deep sea exploration and the ocean as a kid, too?

Mr. Joe Wargo: The answer to that varies from scientist to scientist! For many, their first interest in the ocean came from family trips to the beach, or television programs about the oceans. Many became interested in science because they were fortunate enough to have good teachers.

The research submersible Alvin is a highly complex and versatile tool for exploring the deep sea. Click the image to read more about the Alvin.

Eric-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: How much is the Alvin worth? What is the most complex feature on the Alvin? What does it cost to do a dive on the Alvin?

Mr. Joe Wargo: Just a rough estimate, but it would probably cost about $20 million to replace Alvin today. It's worth a lot more than that! Without her, we would not be able to gain a lot of valuable knowledge about the deep sea. The most complex feature is a tough one to answer. The mechanical and electrical components are pretty complex. The most complex thing, though, is that all of those systems have to work together! To dive the Alvin, you would have to rent Atlantis and all the support crew as well. Total cost is approximately $30,000 per day.

Emily-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: What was your favorite part of exploring the Deep East?

Mr. Joe Wargo: My favorite part of the Deep East exploration is late in the afternoon when Alvin returns. There are living and non-living samples brought back for many scientists from a wide variety of disciplines.

Brittany-Dunn Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: How did you become a Deep East scientist?

Andrew Shepard: Several of us took different paths to the expedition. Most of the scientists and students were chosen because they won a competition called peer review. These scientists submitted proposals to one of the National Undersea Research Centers, which were ranked by mail reviewers and a panel, and then picked from dozens of other projects. Most of the other people on the expedition operate the ship and submersible.

Laura-Harrington Middle School, New Jersey: What were some of the ideas that you and the other explorers exchanged during the Deep East voyage?

Andrew Shepard: This is a very good question for all the Deep East legs. We tried hard to have a mix of different experts on the expedition-- scientists from biology, chemistry, physics and geology, plus an educator and TV crew. This combination of minds and ideas is very effective, especially on an exploration mission like Deep East, where we encountered new areas and events. For example, yesterday a geologist reported seeing golf ball sized mud balls scattered around the bottom. Our microbiologist jumped up and asked to see the video. She found that they are rarely studied, delicate xenophyophores -- or giant amoeba that live in little bushy mud houses.

(top)

Bradley: What kind of medical support does the vessel have on board for the staff and guests?

Andrew Shepard: The ship has a hospital, which is a couple of staterooms with supplies. The medical supplies are given by the Chief Mate or other person designated by the Captain. Most members of the crew have CPR and first aid training. The ship operators subscribe to the Medical Advisory Systems, Inc., which provides 24 hr. advice from physicians.

Dr. Michael Bothner holds a sediment sample collected from Hudson Canyon. Click image for larger view.

Andrew-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Was the bottom of the ocean in Hudson Canyon affected by the dumping of chemicals? Did they seep into the ground?

Dr. Michael H. Bothner: One surprise to me when I observed the sea floor beneath the 106-Mile Dumpsite is that visually I couldn't see evidence of dumping. The sediments were a normal color (light brown to gray), and there were very few pieces of trash or litter. I only saw one tin can, part of a newspaper and a dinner plate on one dive in the middle of the dumpsite. All of these items could have been tossed from a passenger ship. The chemicals that we expected to find from dumping (like silver - from photography, and linear alkylbenzene - from detergents) were higher in concentration near the dumpsite than at control sites upstream. The concentrations were not higher than levels thought to be dangerous for marine animals from coastal areas. However, there is very little information about the toxicity of contaminants like silver, mercury and lead on deep sea animals. This is an important concern when we discharge chemicals and other wastes to the ocean. The chemicals that settle onto the sea floor do not seep into the ground like they do on land after a rain storm. Rather, they get mixed into the sediments below the sea floor by animals that live in and mix the sediments as they move around looking for food. Worms of different types mix sediment, for example. Currents can also mix chemicals below the sea floor, and of course, new sediment can bury older contaminated sediments. For more information on ocean dumping click here.

Nick-Medford Memorial Middle School, New Jersey: Were there any weird mutations of animal and marine life near DWD 106?

Dr. Michael H. Bothner: We didn't notice any weird mutations. The relative abundance of some species of polychaete worms increased in sediments that received sewage sludge. When you add organic matter to marine sediments, opportunistic species of worms typically increase in numbers. In addition, analysis of sea urchins using stable isotopes of sulfur and nitrogen proved that the sludge-derived organic matter was indeed being consumed by animals living on the sea floor. This was an important finding, but unusual mutations were not reported.

Laura: When did they first ban ocean dumping? Why did they want to dump in the ocean all the time?

Dr. Michael H. Bothner: Under the terms of the Ocean Dumping Bay Act of 1988 (dumping defined as discharge from barges) the 106-Mile sewage sludge dump site was officially closed at the end of 1991. NYC continued to dump there until July 1992 (with penalties). I think the reason ocean dumping was attractive is that material dumped in the ocean "disappeared", and there are fewer and fewer safe dumping alternatives on land. We know now that pollutants dumped in the ocean can be a continuing problem because they can degrade habitats for marine animals and sometimes fish that we eat become contaminated. One important step in waste and toxic management is to stop pollution at the source. Toxics from industries and homes should be removed before they enter the sewer lines. Plastics and paper should be recycled whenever possible. There are good examples of success in these areas. It is now possible (and a requirement) to recover silver from the waste streams of film processing companies and hospitals. The value of silver recovered helps pay for the process that prevents it from being discharged into the sewers.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.