by Tom Kok, Mechanical Engineer

August 6, 2010

A deep-sea chimaera. Chimaeras are most closely related to sharks, although their evolutionary lineage branched off from sharks nearly 400 million years ago, and they have remained an isolated group ever since. Like sharks, chimaeras are cartilaginous and have no real bones. The lateral lines running across this chimaera are mechano-receptors that detect pressure waves (just like ears). The dotted-looking lines on the frontal portion of the face (near the mouth) are ampullae de lorenzini and they detect perturbations in electrical fields generated by living organisms. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

The ROV control room aboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer is mission central, serving a variety of operations from mapping to ROV operations to managing interactions between the ship and shore. This view shows the control room during ROV operations. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 937 KB).

They say a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. For me, a journey of several thousand miles began with a single phone call. That call came from Dave Lovalvo, the Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) Operations Manager on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. When Dave asked me if I was interested in traveling to the Okeanos Explorer to work with the ROV team, I had no practical experience with ships, no practical experience with ROVs, and absolutely no idea what to expect. As a recent mechanical engineer graduate, I was about to embark on an exciting and challenging voyage known as ocean exploration.

Little Hercules examines a collection of hydrothermal vents on Kawio Barat. The ROV team works many hours behind the scenes to keep Little Hercules in top condition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 505 KB).

Only moments after arriving on the ship for field trials in February, I began to appreciate the extent of my first challenge: learning about the Little Hercules ROV. Like most ROVs, Little Hercules is a carefully arranged collection of pressure housings, sensors, oil-filled hoses, and delicate electronics. Each component has its own capabilities, limitations, idiosyncrasies, and role to play within the larger system. Both the camera platform and Little Hercules, for example, have altimeters to determine the distance to the seafloor. However, as I’ve worked with the system, I’ve discovered that while the Little Hercules altimeter works well at altitudes below 45 meters, the camera platform altimeter works well at up to 95 meters of altitude but has trouble when the altitude gets below 15 meters.

Unexpected details like this occur throughout the ROV system and learning all of them requires effort and experience. As I continue to learn about each piece of Little Hercules, I find myself with a growing appreciation for how the entire system works together and how much remains to be learned. The challenge of learning every day keeps me interested and engaged with this project during the long weeks at sea.

Some incredible imagery of undersea creatures has been collected during this expedition – from an octopus on the hunt, to a group of feasting crabs, and incredible close-up images of shrimp revealing eyes and long legs. This image captures a shrimp with long legs on a sponge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

A stunning 10-armed sea star. Image captured by the Little Hercules ROV at 271 meters depth on a site referred to as 'Zona Senja' on August 2, 2010. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

The technical details of Little Hercules, however, are not the only exciting challenges aboard the Okeanos Explorer. Day-to-day ROV operations require a high level of expertise and often test me in new and unexpected ways. For example, it might be necessary between dives to swap a poorly functioning sensor out for a spare, test new software controls, or catch up on documentation.

The excitement doesn’t end when Little Hercules is in the water. As a recently initiated pilot of Little Hercules, I regularly find myself performing a delicate balancing act. Adjusting to strong currents and treacherous terrain while still creating quality pictures can be difficult, but a pilot’s real difficulty is finding time while flying to communicate with the rest of the ROV team and with scientists on shore. With so much happening at the same time, I’m rarely confronted with dull moments in the pilot’s chair.

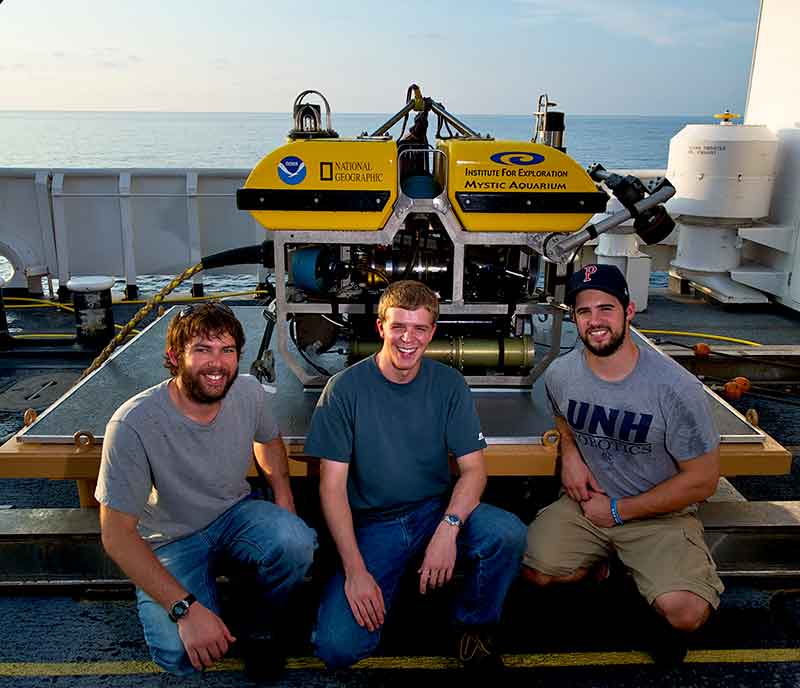

From left to right: Dave Wright, Tom Kok, and Brian Bingham look up for a moment while operating the ROV. Every day presents the pilot, co-pilot, and navigator with new and unforeseen challenges. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 4.7 MB).

Finally, an account of exciting new challenges on the Okeanos Explorer would be incomplete without mentioning mapping. Before each ROV dive, the ship conducts a survey of the dive area with its multibeam sonar. I joined the ship early in Guam to learn how the multibeam works and how to operate it. Now, I’m one of three ROV team members who also stand four-hour, rotating watches while the ship is mapping. While not as obviously exciting as an ROV dive, mapping is a technically challenging and precise science that supplies invaluable information to both the ROV team and scientists. Mapping is another new experience for me to enjoy and learn from.

When Dave asked me to join the team for sea trials in February, I had no experience and no idea what I would find on the ship. Now, six months later, I have a little more experience and I know that I can always expect to find challenges, excitement, and new things to learn aboard the Okeanos Explorer. That’s not to say that life aboard the Okeanos Explorer is always exciting (it’s not: when we are out to sea, we work long days with no weekends and nowhere to go on our time off), but for me the new experiences and new skills are well worth the long weeks at sea.

ROV team members Karl McLetchie, Tom Kok, and Joel De Mello (from left to right) pose in front of Little Hercules. Even with the ROV secure on deck, work continues with routine checks and maintenance. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 4.8 MB).

As this trip to Indonesia draws to an end, I look forward learning new skills this winter while improving the ROV system and returning next year ready for a new round of challenges and adventures. This trip may be ending, but my voyage of ocean exploration has just begun.

Galatheid crabs and a large shrimp feast opportunistically on a pelagic catch. The largest crab individuals were feeding directly on the catch, whereas the smaller crabs waited their turn to feed on the outskirts of the group. Image captured by the Little Hercules ROV on a site referred to as 'Zona Senja' on August 2, 2010. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 1.9 MB).

A benthic fish called a sea robin. This fish has several sets of modified fins – some modified for perching on the seafloor and 'wing-like' fins for swimming. Image captured by the Little Hercules ROV at 279 meters depth on a site referred to as 'Zona Senja' on August 2, 2010. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 918 KB).