By Chris German, Science Team Lead/Senior Scientist - Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Mission Summary

From the very first moment of the very first dive we were able to land the ROV right at the summit of the central Von Damm hydrothermal field. Even then, I was not prepared for the 8m tall spire that we found and certainly not for the more than 1m wide orifice emitting hot fluids from close to its summit! Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

One of the interesting geological findings during the expedition included this orifice more than 3 feet wide – about the same size as the Little Hercules ROV – emitting hot fluids near the summit of the central Von Damm vent spire. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

After an intense and extraordinarily productive 11 days on station along the Mid-Cayman Rise, suddenly the last dive has been completed, the last planned sections between the Mid-Cayman Rise and Cayman Trough have been mapped and we are headed home. We have about two days’ working time as we steam north around the Western end of Cuba to our final destination – Key West, Florida. I am looking forward to using that time to relax from the necessity of continuously planning what the expedition team and systems aboard ship should be undertaking, scientifically, for the next 24-72 hours ahead and, instead, reflect upon – and begin to evaluate – all the remarkable findings that we have shared.

While I myself haven’t yet had the chance to review any of the data we have collected, I am lucky enough to have shared this experience with many wonderful and talented colleagues both here aboard the ship, at the ECC at URI and throughout much of the Internet-connected world! While many have been working around the clock, as well as around the world, to keep the program moving forward (and, hence, already have much greater and deeper insights into many aspects of the work we have just completed), here are some of the highlights from the expedition that already stick firmly in my mind.

One of the interesting geological findings during the expedition included this orifice more than 3 feet wide – about the same size as the Little Hercules ROV – emitting hot fluids near the summit of the central Von Damm vent spire. Video courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download (mp4, 34.7 MB).

An obvious, great start was that from the very first moment of the very first dive we were able to land the ROV right at the summit of the central Von Damm hydrothermal field. But even then, I was not prepared for the 8m tall spire that we found and certainly not for the more than 1m wide orifice emitting hot fluids from close to its summit – it was big enough to drive our ROV right into (not that we would of course) but, despite my 25 years in this field, that was a first.

During the course of our first dive we found abundant shrimp of a species that Paul Tyler was able to identify as substantively different in appearance from other Mid-Atlantic Ridge species, but it was the second dive in our original survey where I was witness to the first discovery of a live hydrothermal tube worm in the Atlantic that I may take home as my personal key “discovery” moment of the cruise. Later in the cruise we actually made even more remarkable discoveries – not only extensive tubeworm communities of differing size and shape across the length and breadth of the Von Damm field (which is clearly even larger than had previously been suspected) but – and this is a complete first worldwide, we are sure – the discovery of chemosynthetic shrimp and tubeworms inhabiting the same hydrothermal site. The fact that I only had the ROV drive across to that location pursuing hydrothermal fluids and microbial mats is neither here nor there – or, more to the point, exactly why the deep oceans need to continue to be explored onward into the future. I am happy to acknowledge that it was others (notably Diva Amon communicating over our RTS unit from the ECC) who were the first to identify the significance of what we found that morning. I was simply too happy marveling at the beauty of the sight unfolding in front of me and feeling privileged, first to have the chance to witness this scene at all, and second, to be able to share the magic of that moment with so many friends, colleagues – and even complete strangers! – around the world, first hand. I can only hope you enjoyed it half as much as I suspect you could all tell that I did!

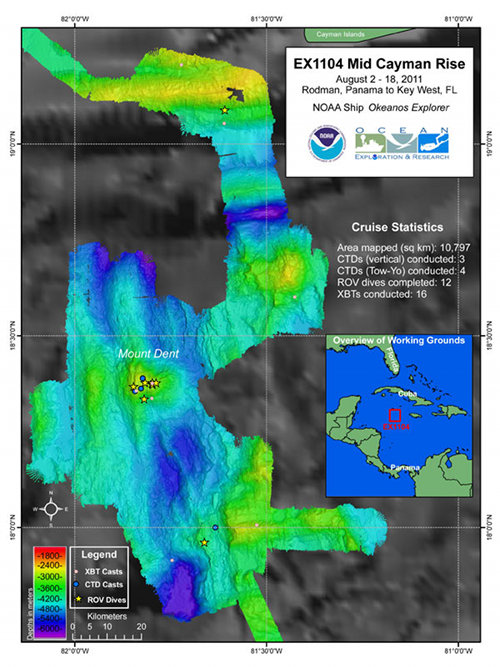

Overview map summarizing the work completed by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer and the expedition team during the Mid-Cayman Rise 2011 expedition. Nearly 10,800 square kilometers of the seafloor was mapped during the expedition using the ship’s deep-water multibeam sonar. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 2.6 MB).

Of course, our discoveries have not only been made during our ROV operations – we have conducted CTD casts long into the night here, urged on by my colleague Dr. Sarah Bennett at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab who kept me going with a steady stream of stimulating discussion through our Internet 1 and EventLog forum, and then stayed up long after I had gone to bed to process the data. So did Cameron McIntyre, out here at sea, analyzing and preserving the water samples we collected, so that we would have a whole new suite of data to work with the next morning as soon as we woke up. Likewise, the survey team out here have proven to be a team of relentless mappers who seemed determined to outbid the enthusiasm of Mike Cheadle and Bobbie John back ashore in terms of their achievements. The more Mike and Bobbie enthused about the quality of each night’s data, the more Meme Lobecker and her team responded by providing even more high quality data that transformed our appreciation of what was happening at the seabed beneath us.

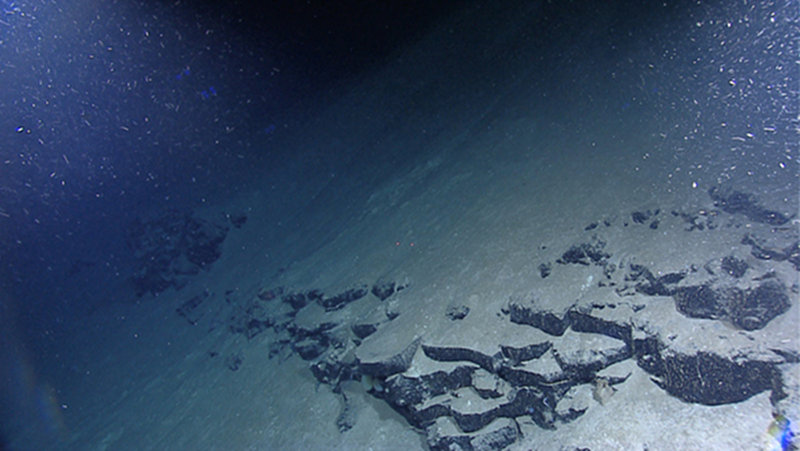

Frozen sheet flow, examples of how lava must have flowed out over the seafloor here at 3500m depth at the Mid-Cayman Rise. Frozen sheet flow was imaged by the ROV during the tenth ROV dive of the expedition at the Mid-Cayman Rise, an ultra-slow spreading ridge. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Indeed, while I like to think that I have done a bit of geology in my time (but nothing I couldn’t handle!) I found myself increasingly drawn away from the biological side of our explorations as the mission continued toward the geological buzz. Maybe the best illustration of that was that on our second Saturday dive, when I changed the weekly tradition of having a magic word of the day from “Tube Worm” to “Sheet Flow”. Time was (including when I was a student) that received wisdom would insist that you shouldn’t expect to find either sheet flows or tube worms at such a slow-spreading mid-ocean ridge as the ones you get in the Atlantic. Who knows what else we might have discovered had we stayed here for a third weekend? Non-extinct underwater dinosaurs? Now I am happy to be headed home to see family, friends, my dogs, and even spend some quality time back at the office where I can begin to take more detailed stock of everything that just happened.

I hope those of you following the expedition at home have enjoyed this experience as much as I know that Paul Tyler, my fellow watch-leader, and I have. It only remains for me to thank everybody aboard the Okeanos Explorer and throughout the NOAA Ocean Exploration and Research program that have made this experience possible for all of us. I hope and trust that it will not be too long before we all get to do this all over again, whether it be from the beach or out on the ocean waves.

Either way, and until then– Onward and Downward!