By Tom Weber, Research Assistant Professor - University of New Hampshire Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping

April 18, 2012

Bubbles of methane gas rise through a mussel bed at the Pascaguola Dome. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Dive 06 of this expedition really began about seven months ago during what we call a water column mapping cruise on the Okeanos Explorer. During this earlier cruise, we used the echo sounders on the ship — a 30-kHz deepwater multibeam and an 18-kHz split-beam — to map acoustic anomalies in the water column.

Video footage captured by the Little Hercules remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and Seirios camera platform during the April 18 ROV dive from NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer the Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. The dive was conducted at a site located south of the Biloxi Dome, where sonar data acquired by the ship in 2011 suggested relatively strong indicators of gas seeps in the water column. During the dive, we located and ground truthed the source of the gas seeps seen in the sonar data and explored new seafloor habitats. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download (mp4, 262.0 MB).

We were mainly looking for evidence of natural seeps of methane bubbles: gas bubbles rising from the seafloor show up as strong acoustic echoes in the echo sounder data. We made hundreds of observations that indicated the presence of gas bubbles in the water column. This was no surprise — we were mapping in the northern Gulf of Mexico, an oil and gas province known for having many natural seeps. As expected, most of the gas seeps we found were located on the edges of salt domes where faults can provide pathways for deep gas to reach the seabed and escape into the water column.

We were mystified, though, by a few of the seeps that we found in what appeared to be a featureless, flat area of the seabed about five kilometers south of the nearest salt dome — the Biloxi Dome. This was not a location we expected to find seeps. Were we looking at methane bubbles? Why were they showing up so far from the salt domes? Our maps showed we were several hundreds of meters from any human-made structures on the seabed, but were those maps right? Was the origin of the gas bubbles natural? If only we had a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) we could deploy for a closer look!

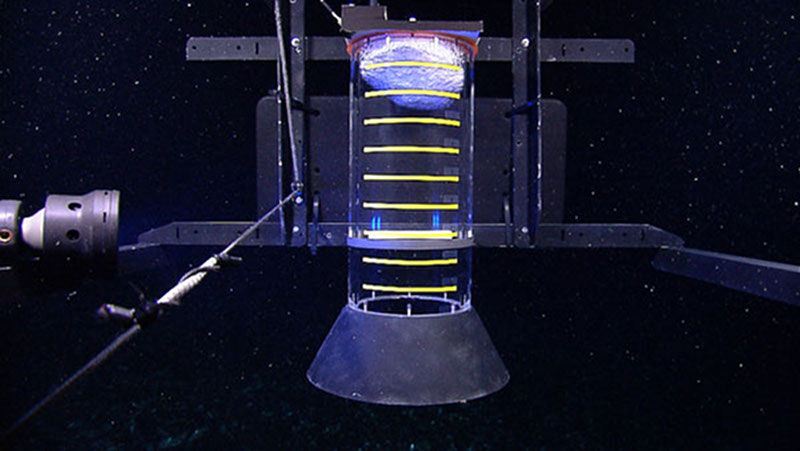

A gas capture device, affectionately known as the methane bucket, is assembled and then deployed by the team on the Okeanos Explorer. The methane bucket allows us to estimate the volumetric flow rate associated with bubbles of methane gas entering the ocean from discrete seep sites. The methane is captured at depth, where it forms a mix of hydrate (methane ice) and gas, and is then brought to shallower, warmer waters, where the hydrate dissociates, in order to estimate the volume of gas collected. On a subsequent dive, a calibrated grid was deployed in order to more accurately estimate the sizes of individual bubbles. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download (mp4, 296.2 MB).

Of course, on that cruise we did not have an ROV to deploy, and so seven months later, we finally got the opportunity to look at our mystery bubble seeps. We chose to examine two that were separated by about 800 meters – a full day of ROV work in over 1,700 meters of water. On previous ROV dives, we focused on creating links between what we observed with the ship’s echo sounders with what we could observe with the ROV (e.g., bubble sizes, flow rates, seep morphology), but this dive was pure exploration.

Sure enough, after we descended deep into the ocean we found a community of tubeworms, mussels, and other organisms indicative of a methane-rich environment. We also found bubbles escaping the seafloor –- the likely source of our acoustic observations. On the 800-meter transit to the next acoustic target, the seafloor was relatively featureless –- much more in-line with what we would normally expect from this part of the deep ocean floor.

Methane bubbles rise into a clear cylinder, designed for measuring gas flux, where they form a mixture of hydrate and gas. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

But as we arrived at our next target site, we once again found a vibrant community of mussels and tubeworms, this time accompanied by exposed methane hydrate and a very steady stream of bubbles escaping the seafloor.

The evidence we generated with the ROV certainly helped answer some of our questions. Yes, the bubbles were most likely methane, and yes, these seeps were of natural origin – and also nicely demonstrated how complimentary the acoustic and ROV observations can be.

Without the acoustic evidence of gas within the water column -- data that can be efficiently gathered by the ship -- we would probably never have visited these sites in the first place. But the shipboard acoustic data sometimes leaves unanswered questions and without the close-up look afforded us by the ROV, we would not have been able to determine that we were looking at two chemosynthetic oases in the deep ocean.

Exploring these type of environments with both of these observation tools seems to be working quite well for us!