By Dr. James (Jamie) A. Austin, Jr., Science Lead, Leg 3, Gulf of Mexico 2012 Expedition - Senior Research Scientist, Institute for Geophysics, Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin

April 29, 2012

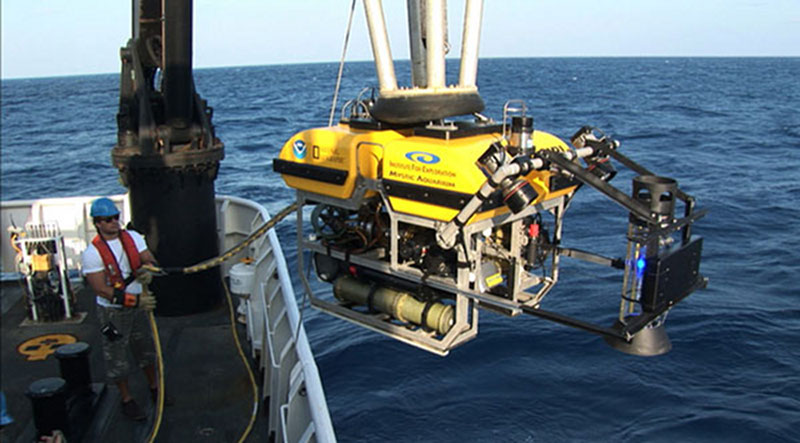

A gas capture device, affectionately known as the methane bucket, was added to the front of the Little Hercules remotely operated vehicle for several dives. Gas from natural seafloor seeps was captured in the device at depth, where it forms a mix of hydrate (methane ice) and gas, and was then brought to shallower, warmer waters, where the hydrate dissociated, in order to estimate the volume of gas collected. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

The third and final cruise of the Okeanos Explorer’s 2012 Gulf of Mexico Expedition had three primary objectives:

Of the 13 remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dives conducted during Leg 3, the first six dealt with the seep objective. Multiple seeps on the seafloor were identified in several areas, predominantly along the flanks of surfacing salt domes, and escaping bubble streams were imaged in detail.

Gas bubbles from a natural seep rise up in front of a calibrated grid added to the front of the Little Hercules remotely operated vehicle, enabling the collection of imagery data that will allow scientists to assess sizes and rates of bubble escape from a seep. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

In addition, bubbles were captured using an inverted clear cylinder on the ROV, and the resultant clathrate (frozen gas hydrate, a mixture of water and methane ice) was allowed to turn back into gas as the ROV rose slowly to the surface. This allowed investigators to measure volume precisely. Bubble streams were also calibrated using a visual grid affixed to the ROV.

Two shipwrecks were investigated, one in 400 meters of water near the Mississippi Canyon and the other in 1,330 meters of water east of the Keathley Canyon. The first, perhaps the best-preserved wooden shipwreck in the Gulf, measured 61 meters in length and appears to be a heavily built sailing ship. The second was a wooden-hulled vessel sheathed in copper, filled with artifacts including bottles of all shapes, sizes and colors, plates, multiple anchors and cannon, and stacked muskets. Archaeologists are speculating that this may have been a privateer from the early 19th century, but a lot of work must still be done to confirm or deny these early conclusions.

While most of the wood has long since disintegrated from what is believed to be an early to mid-19th century wooden-hulled shipwreck on the deep Gulf of Mexico seafloor, copper that sheathed the hull beneath the waterline as a protection against marine-boring organisms remains, leaving a copper shell retaining the form of the ship. The copper has turned green due to oxidation and chemical processes over more than a century on the seafloor. Oxidized copper sheathing and possible draft marks are visible on the bow of the ship. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

A giant snake eel pokes its head out of the scupper along the port side of shipwreck MC 195, resting approximately 400 meters deep on the Gulf of Mexico seafloor. A scupper is a pipe that passes through the bulwark on the weather deck, or top deck of a ship. Water collecting on the deck from rain or high waves to drains through the scupper and flows over the side of the ship. Lollipop sponges and several different kinds of anemones inhabit the wooden planking of the wreck. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Two red Anthomastus octocoral (a large one and small one), a squat lobster (Munidopsis sp.), an anemone, and several shrimp were imaged on a rocky outcrop during a dive at the Sigsbee Escarpment. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Finally, reconnaissance dives were conducted on the Sigsbee Escarpment and in the Keathley Canyon. The Escarpment itself was a wall of mudstone, often vertical, with many deep-water coral communities. In contrast, the flank of the lower western wall of the canyon was entirely sedimented, with no outcrops and only sparse encrusting biology. However, all of the dives recorded fascinating arrays of organisms living in many different symbiotic arrangements.

The success of Leg 3 is a tribute to the Okeanos Explorer team, her dedicated crew, and the ongoing telepresence paradigm serving ocean exploration.

While it's nearly impossible to get a picture with all expedition participants, this image captures the mission personnel who were on board NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer during the third and final cruise leg of the 2012 Gulf of Mexico Expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 5.3 MB).