By Jack Irion - Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Frank Cantelas - NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Chris Horrell - Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement

Jim Delgado - NOAA Maritime Heritage Program

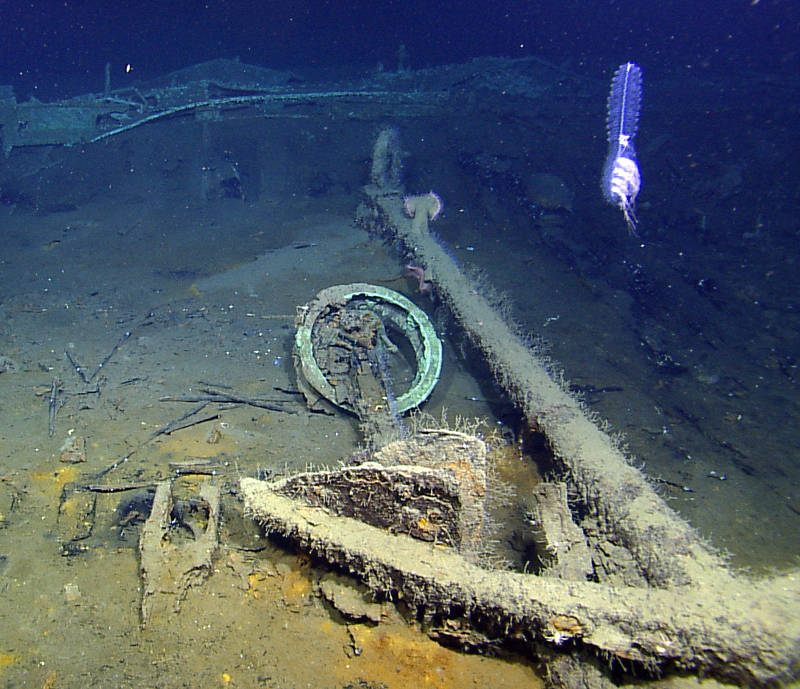

Lying next to an anchor are the remains of the capstan from the Monterrey C site in more than 4,300 feet of water. In the background are fragments of the hull’s copper sheathing. The wreck is one of three sites investigated by scientists from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, NOAA, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, the Texas Historical Commission, and the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University. Image courtesy of the Ocean Exploration Trust/Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, Texas State University. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

In the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, our nation’s collective maritime history and culture, in the form of shipwrecks, lies embedded in the seafloor. NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (OER) and its partners have previously explored many of these sites.

During the 2014 Gulf of Mexico expedition on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, we hope to visit four sites; three have been partially explored and the fourth is a side-scan sonar target that we suspect may be a shipwreck.

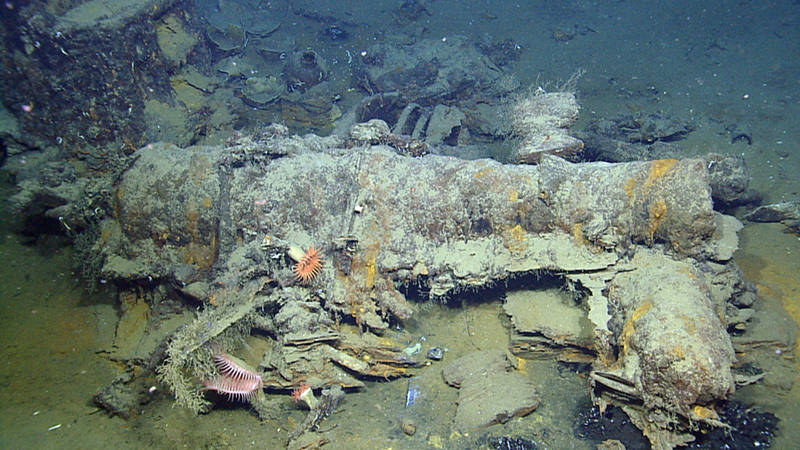

The large cannon on the Monterrey A Shipwreck appears to have been mounted on a pivot carriage which has led archaeologists to believe the site may be the remains of a privateer. The muzzle, on the right, rests on top of another cannon. The image illustrates that the Monterrey Shipwrecks are home to a diverse biological community. Exploration conducted at these sites provides not only a window into the past but also reveals how, over time, the deep-water environment affects shipwrecks and how shipwrecks affect the environment. Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust/Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, Texas State University. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

The first three targets are a cluster of vessels collectively known as the Monterrey Shipwrecks that appear to date from the early 19th century. Monterrey Site A, first explored on the 2012 Okeanos Explorer Gulf of Mexico expedition, turned out to be an extraordinary wooden shipwreck.

Our data suggests that this may very well be the remains of a well-armed privateer. The site contains an amazing collection of artifacts dating from the early 19th century—a turbulent period of nation building, civil war, and independence movements in the counties and colonies surrounding the Gulf including the growing United States and Latin America.

The tantalizing video captured on the 2012 Okeanos dive sparked a follow-up exploration mission by a team of interdisciplinary scientists from federal and state agencies and academic partners in July 2013, on the Ocean Exploration Trust’s exploration vessel Nautilus.

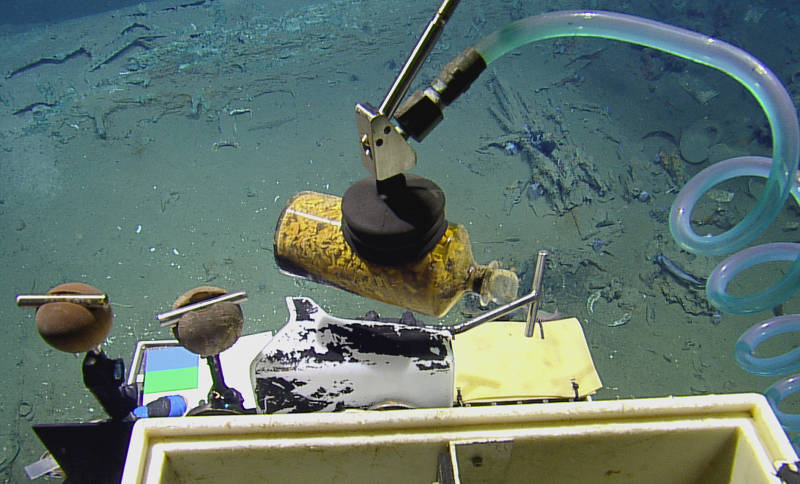

Using the high-tech remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Hercules, the onboard archaeology team in 2013 conducted precision mapping and photogrammetry of the site; collected diagnostic artifacts for detailed analysis; and imaged the site in high-definition video to better understand its age, national origin, function, and historical significance.

The biology team, participating via telepresence from Texas A&M at Galveston, Texas, documented the deep-sea inhabitants of the wreck and guided the collection of anemones and cnidarians. Hercules also deployed a set of experiments at the wreck to assess the colonization and consequences of wood-destroying organisms. These experiments will remain on the seafloor for several years to document the communities that establish on and within newly introduced wood in the deep sea and assess the processes by which these organisms consume and degrade different woods used on 19th century ships.

The ROV Herculesgently recovers a medicine bottle filled with ginger, a seasickness remedy, from an early 19th century shipwreck recently documented and partially excavated in the Gulf of Mexico in more than 4,300 feet of water. Image courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust/Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, Texas State University. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

After characterizing Monterrey A, the team shifted attention to investigation of two unknown side-scan sonar targets less than five miles away, reported to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management by Shell Oil. To the archaeologists’ astonishment, both sites proved to be historic shipwrecks with very similar artifacts to those of Monterrey A, suggesting they sank during the same time period.

Monterrey B appeared to be a heavily constructed, unarmed merchant ship transporting a large cargo of what appears to be animal hides, blocks of a substance that may be tallow, and still unopened crates. Surprisingly, much of the ship’s wooden hull, including stumps of what appear to be two masts, has survived the ravages of nearly 200 years beneath the sea.

Monterrey C, the largest of the three vessels, was copper-sheathed like Monterrey A, carried an enormous anchor in the stern, and sported a brass-bound capstan. Unlike the other two vessels, Monterrey C has a substantial amount of stone ballast that had shifted violently to the stern when the ship came to rest on the seafloor. This may suggest that the vessel did not carry a cargo or had a perishable cargo on board at the time she slipped beneath the waves.

The fact that Monterrey wrecks A, B, and C are so closely clustered together also suggests that they may have all gone down together, possibly during a storm. The discovery of three contemporary shipwrecks lying so close together, yet so far from land, is truly unique and provides an important archaeological assemblage from which we can learn more about the Gulf of Mexico’s maritime history and heritage.

Target WR0325 was discovered in 2010, during a survey of the seafloor conducted for Chevron Oil using an autonomous underwater vehicle. A side-scan sonar image captured by the vehicle shows a ship-like target, approximately 230 feet long (70 meters), with fairly high relief at each end. Image courtesy of Chevron Pipeline Company. Download image (jpg, 29 KB).

During this year’s Gulf of Mexico mission, Okeanos Explorerwill return to the Monterrey Shipwrecks. Our brief visit to the new sites in 2013 gathered valuable, but limited, information that highlights the need for better characterization of the biological communities that have found homes at Monterrey A, B, and C. This year, we will also gather more baseline archaeological data to inform resource managers and potential future research. A broad community of archaeologists and biologists from across the country are expected to participate as ROV Deep Discoverer explores these sites.

Finally, we hope to explore a new target (WR0325) discovered in 2010 on a survey of the seafloor conducted for Chevron Oil using an autonomous underwater vehicle. A side-scan sonar image captured by the vehicle shows a ship-like target on the bottom. This will be the first visual survey to identify and document the target.

The excitement and anticipation of exploring a new shipwreck draws tremendous public attention. It also inspires the desire to protect shipwrecks from damage or pillage. This means that new partnerships and collaborations between scientists, governments, and the public will be needed for effective stewardship and management of the wrecks.

Such collaborations are ultimately the most valuable discovery coming from this mission and they will remain an important source for understanding the history and ecology of the Gulf of Mexico and our relationship to it.