By Ian MacDonald - Florida State University

April 24, 2014

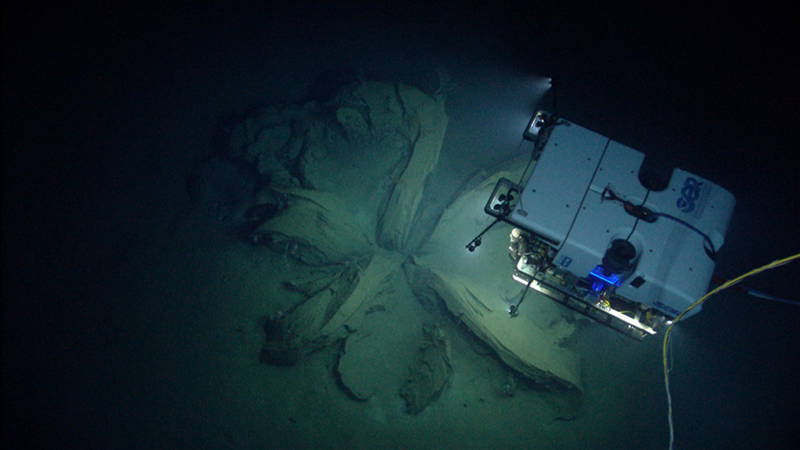

ROV Deep Discoverer approaches the first tar lily. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Sidescan sonar showed a cluster of really big structures at a depth of 1,900 meters in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA explorers steered their remotely operated vehicle, Deep Discoverer (D2), to the bottom thinking that they would be approaching the wreck of a sunken ship.

The presence of chemosynthetic tube worms at the site led scientists to believe that there was more to this site than what we could see. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB). Video highlights from Dive 12.

The archeologists following the dive got ready to note down the shape of the hull and look for telltale debris. Instead, the D2’s cameras revealed massive rocks splayed out over the seabed in the shape of an enormous flower. Except the forms were not really rocks either; parts were rounded like they had been squeezed out of a tube and there were dozens of cracks and fissures revealing a smooth black substance. What on Earth could this be?

Within a few minutes, the scientists on the dive realized that they were looking at a much unexpected example of an asphalt volcano. Volcanoes form when material expelled from deep within the Earth creates a large structure standing above the surrounding land or seascape.

Glowing streams of molten rock are what most people think of when they hear the word “volcano.” But eruptions of mud, shale, and salt are also known to form volcanoes. In 2004, scientists on the German ship F/V SONNE reported asphalt volcanoes 3,000 meters deep in the southern Gulf of Mexico. Later reports confirmed similar asphalt volcanoes off the coast of California and West Africa. Today’s discovery expands the number of known examples and confirms the existence of an asphalt ecosystem across the Gulf.

After documenting the first asphault extrusion, D2 investigated a second sonar anomaly which turned out to be another “tar lily”. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

The asphalt at this site is produced by the same processes that generate oil and gas, but has been transformed by geology and then altered again when it is exposed to cold seawater. The Gulf is full of oil platforms that drill into reservoirs of oil and gas and pump it ashore for energy. Some reservoirs are so old that the oil they contain has been “cooked” for millions of years. Heating causes the volatile components to evaporate, leaving behind a thick, gooey remnant. Think of how you could dissolve grease in gasoline, and what would be left behind if all the gasoline then evaporated.

In refineries, the gooey residue that remains after extraction of gasoline and other products is mixed with sand and then mixed with lighter oil and heated up to make it flexible enough to pave roads. At a deep-sea asphalt volcano, the material is squeezed out in huge ropey masses that bend and flow. In the cold seawater, the remaining volatiles dissolve and the extrusions shrink in volume. At some critical point, the asphalt cannot flow anymore. Cracks and fractures form.

Here you can see a close up view of one of the “tar lily” “petals.” The first asphalt extrusion had a number of corals and anemones colonizing it. These organisms allowed our science team to give these features an approximate age on the order of tens to hundreds of years old. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

This process would explain the basics of what the NOAA explorers discovered today. A massive plug was squeezed out at the seafloor. It then split into separate extensions that continued to flow until they became brittle and cracked apart. Once the petals of the giant lily were in place, animals that like hard surfaces had a new home. People following the dive saw beautiful video of corals, barnacles, anemones, and fish. Bacteria that can utilize the oil as food generated a sulfur-based food chain for chemosynthetic tube worms and mats of other sulfur oxidizing bacteria.

Although the asphalt volcano appears to be dormant for the moment, the size of the extrusions suggests that there may be more asphalt below that might get squeezed out in the future.