By Anthony Tully

IJN destroyer Hayate. Download larger version (jpg, 345 KB).

Like the other Japanese invasion operations that were to take place simultaneously with or just after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1944, the invasion and capture of Wake Island had been laid out in advance, and its forces already allocated. On December 8—the same day of the Pearl Harbor attack for this was west of the International Date Line—this force under Rear Admiral Sadamachi Kajioka departed Kwajalein Atoll for Wake Island, the landings scheduled for late December 10th. This force was comprised of Kajioka’s flagship light cruiser Yubari and its Destroyer Squadron (Desron) 6 made up of two destroyer flotillas Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 29 comprised of Oite and Hayate, and DesDiv 30 comprised of Mutsuki, Kisaragi, Yayoi, Mochizuki. The invasion forces of the 2nd Maizuru SNLF would be carried aboard some of the destroyers, but also aboard two converted old destroyer transports (PBs No.32 and No.33), and the armed merchant cruiser Kongo Maru and transport Kinryu Maru. The latter pair also carried two Aichi E13A1 recon seaplanes each in addition to equipment for the troops aboard. Finally, in addition to the air attacks from Majuro and Roi commencing on 8 December, gunfire support on invasion day would be available from two old light cruisers of Rear Admiral Kunimori Marumo’s Cruiser Division (Crudiv) 18, Tenryu and Tatsuta.

American defensive positions on Wake Atoll, 8-23 December 1941. Image courtesy of Anthony Tully. Download larger version (jpg, 218 KB).

The Japanese force arrived off Wake Island on the evening of December 10. An initial attempt was made to disembark troops to their Daihatsu landing barges from the transports (Kinryu Maru and Kongo Maru) and SNFL forces on PBs No.32 and No.33 that night, but was frustrated by heavy seas. The wind and waves were so strong some barges were overturned, and it was clearly not safe. Desron 6 had to postpone the landing to daybreak on 11 December. As if this was not distraction enough, the U.S. submarine Triton fired four torpedoes at Yubari, but they missed.

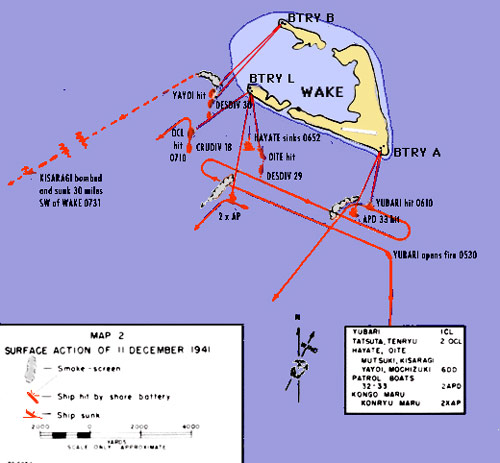

As a result, it was 0500, just as dawn was breaking, that the assigned warships began to advance to their designated bombardment positions and targets. The defenders ashore spotted them, and repeatedly warned by Major Devereaux not to open fire till ordered, had to watch tensely as Desdiv 29 (Hayate, Oite), the cruiser Yubari (force flagship, Rear Admiral Kajioka) followed by Desdiv 30 (Mutsuki, Kisaragi, Yayoi) and cruisers Tenryu and Tatsuta in column:

“reached a position approximately 8,000 yards south of Peacock Point, turned westward and commenced a run [bombarding], broadside-to, paralleling the south shore of Wake. Keeping about a thousand yards further to seaward of the still silent island, the other enemy ships likewise turned and proceeded westward. Although the enemy were not yet aware of it, the Yubari was already being tracked by Battery “A” (5-inch seacoast) on Peacock Point from which camouflage had been removed so that the guns could train.”1

Surface actions around Wake Atoll on the morning of 11 December 1941. Japanese warships approached from the south to bombard the island before encountering fire from American shore batteries. Image courtesy of Anthony Tully. Download larger version (jpg, 166 KB).

Just before Yubari completed the westward run along the shore of Wake and reversed course, Desdiv 29 split off and steamed rapidly in, heading directly for the Wilkes Island shore. Yubari then reversed course toward the atoll, thus closing range, and steadying on southeastward course, again opened fire. Battery “A” on Peacock's Point held fire until Yubari reached a “position almost due south of Battery “A”, some 4,500 to 6,000 yards distant. Battery “A”'s rangefinder had been put out of action during the air raid on December 9, but, using estimated data, the battery range section was already plotting the target, and the gun sections were standing by to fire. At 0615, the defense detachment commander, now standing on the beach beside his command post, gave orders to commence firing.”2

A few shells hit Kajioka’s flagship’s port side as she turned sharply away to the left and began a zigzagging flight southwestward, returning fire as she did so. By the time Yubari cleared the area the Japanese force had suffered further setback, in fact, disaster.

While Battery A was firing on Yubari and company, 5-inch Battery “L” on the western end of Wilkes Island under command of Lt. John A. McAlister was tracking the onrushing Desdiv 29. The battery was partly shielded by sandbags and local brush; the latter which was now swiftly cleared out of the way. The Japanese destroyers were firing as they closed, landing shells on the beach, but still not detecting the battery. “Approximately 4,000 yards offshore, they executed a left [westward] turn, and the leading ship, Hayate, was just settling down on a run close along the shore of Wilkes when Battery “L” opened fire. At 0652, just after the third two-gun salvo, the Hayate was swallowed up in a violent explosion, and, as the smoke and spray drifted clear, the gunners on Wilkes could see that she had broken in two and was sinking rapidly. Within two minutes, she had disappeared from sight.”3

An eyewitness—Private Jack Skaggs 1st Marine Defense Battalion—a member of Battery “L” reports regarding Hayate in a video interview that a hit was scored on the second salvo setting off such an explosion “that the whole back half of the ship blew off.” If this is correct, a 5-inch/51 caliber shell most likely struck Hayate's No.2 or No.3 torpedo tubes—both which were adjacent to one another amidships aft—and destroyed the vessel. From Private Skagg’s description a depth-charge explosion seems less likely. In any case, it would appear the forecastle torpedo tubes were not involved. At the time she was struck, Hayate was reportedly on a northwest course, with guns trained to starboard, and headed to steam along the Wilkes Island south shore. Allegedly the turn to port had just been made and the destroyer was broadside when hit by shells in her starboard side. Hayate sank so fast there was little time for any to get off. The prospects for survivors were made worse by no chance for other ships to do much rescue. There was only one survivor, and lost were Lt. Cdr. Takatsuka and 167 men. The condition of the wreck and relative size of sections remaining will depend on whether the explosion was torpedoes or the stern depth charges. In any case these were small destroyers, little over 1,500 tons and of limited strength to withstand large detonations. In the writer’s opinion the explosion of the torpedo tubes better explains the immediately being blown in two and sinking at once—“instantaneously” in the Japanese phrasing.

The history of Japanese Destroyer operations by Kimita Jiro confirms the general outline of what the Marines observed. “Now at dawn, Desron 6 stood in close and parallel to the beach, and opened fire. The enemy Marines manning their shore batteries replied, and this exchange went on for perhaps 20 minutes. Then suddenly at 0452 [Tokyo time] black smoke billowed from the aft part of Hayate and a tremendous explosion resulted. She had been hit at a range of 5,400 meters by at least two 12.7 cm shells and she broke in half and sank.”4

The Japan Defense Agency History offers a few more details of the moment of explosion: “—‘At first black smoke arose from the stern of Hayate, and immediately the smoke covered the whole ship. The bridge was seen during intervals of smoke. [But] when the smoke disappeared, the ship could not be seen. At that time, there was no enemy plane in the sky.’ These were the situations as reported by the commanding officer of Kongo Maru and gunnery officer of Yubari,”5

“For a moment, the effect of Battery “L”'s shooting proved too much for the 5-inch gun crews, and firing was involuntarily checked until a veteran non-commissioned officer broke the spell and reminded the Marines that other targets remained.”

“Fire was then shifted onto Oite, the destroyer which had been following Hayate, now so close to shore that Major Devereux was forced to forbid .30 caliber machine gunners from trying to open fire. One hit was observed before the troublesome onshore wind smoke-blanketed the target, which had already turned to seaward, leading the remaining ship of the division away from Battery “L.” Several more salvos were fired into the smoke, but splashes could not be spotted, possible evidence in itself that the shells were hitting... Approximately 10,000 yards offshore, the two transports Kongo Maru and Konryu Maru steamed almost due south of Wilkes. McAlister checked fire against the retiring Oite and trained onto the leading transport. After being hit once, she too turned to seaward and retired...”

The Japanese destroyer history relates that Oite at first moved to rescue Hayate’s crew, but was then struck by a shell near No.4, the rear main gun turret, which wounded four crewmen. Then strafing by enemy Wildcat fighters dissuaded any further attempts (only one rescued). At the same time Yayoi was hit in her radio room under the bridge, killing and injuring several. Seeing this, Kajioka signaled from Yubari for all ships to abort the landing operations. Instructions were made that for now the troops were to remain aboard the transports and all barges already in the water to return immediately and be hoisted back aboard. Desron 6 complied, turning sharply away and beginning to retire from the scene.6

The Japanese were commencing to withdraw, but the Marines were not quite through. At this time Battery “L” commander got a bead on a cruiser steaming northward some 9,000 yards offshore of Wilkes Island, and let fly a few salvos. One hit was claimed aft, and the cruiser turned even sharper away, trailing smoke. Battery “B” on Peale Island had also gone into action, landing a hit on destroyer Yayoi. With that, the epic first stand was over. By 0710 no targets remained within range of Wake Island’s batteries. Battery “L” for its part had fired approximately 120 rounds, and had sunk one Japanese destroyer, and damaged a cruiser and three destroyers. For all this, only two Marines had suffered minor wounds from shrapnel in return.

Nor was this quite the end for the roughly handled Japanese force. As they retired, they came under air attack from Wake’s VMF-211. At 0731 the destroyer Kisaragi was hit by a bomb, and exploded and sank bow first with all hands. Cruisers Tenryu, Tatsuta, and Yubari were also damaged in the air attacks. By the time the ordeal was over, RADM Kajioka’s force had lost upwards to 330 men, and had failed to accomplish the planned invasion landings.7

A notable but often overlooked fact of the U.S. Marine defender's achievement is they had in fact sunk the first major Japanese warships of the Pacific War by sending down Hayate and Kisaragi. Unfortunately, this is not generally recognized because the event took place on December 11 west of the International Date Line. Yet Wake Island is 22 hours ahead of Hawai‘i and the sinkings at 0652 and 0737 were in “real-time” terms before the generally accredited first sinking of a Japanese warship, the damaged submarine I-70 bombed in the afternoon of December 10th, northeast of Oahu by a Dauntless dive-bomber flown by Lt (jg) Clarence E. Dickinson Jr from USS Enterprise (CV-6)—a fact of some interest perhaps to unit historians.

1 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-M-Wake/USMC-M-Wake-2.html

2 ibid

3 ibid

4 Kimata, Jiro. Kuchikukan nyumon : Suiraisen no hanagata tettei kenkyu. (Destroyer history) Tokyo: Kojinsha, 2006.

5 Japan, Bōeichō Bōeikenshūjō Senshibu (originally, Bōeichō Boeikenshūjō Senshishitsu), also Senshi Sōsho (War history) series. Asagumo Shimbunsha, Vol. 38, p. 163.

6 Morgan, Jim. Wake Island 1941. Long Island City, NY: Osprey Publishing, 2011.

7 ibid