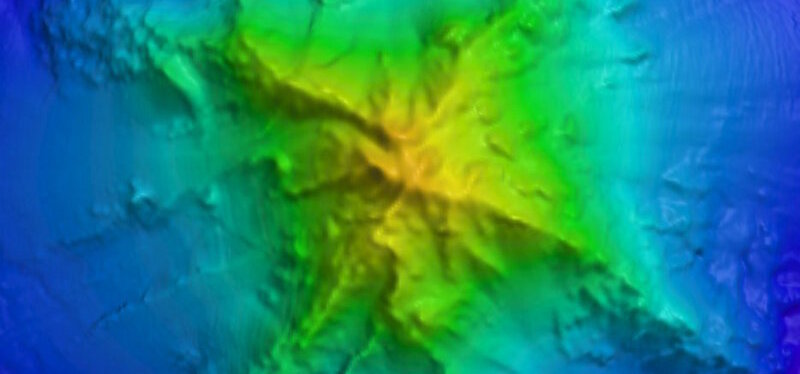

A previously unmapped seamount we are calling "Kahalewai." This seamount has four ridges that radiate outward from the center. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 245 KB).

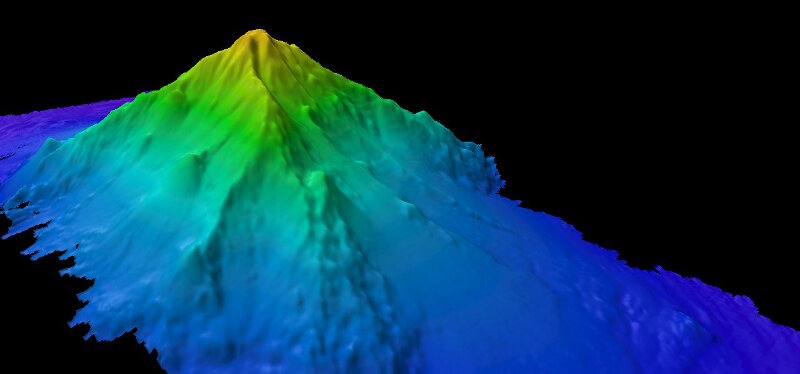

This ~4,200-meter (~13,800-foot) high seamount we are calling "Kahalewai" was almost 1,000 meters taller than previously thought. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 251 KB).