Dr. Rhian G. Waller, University of Maine

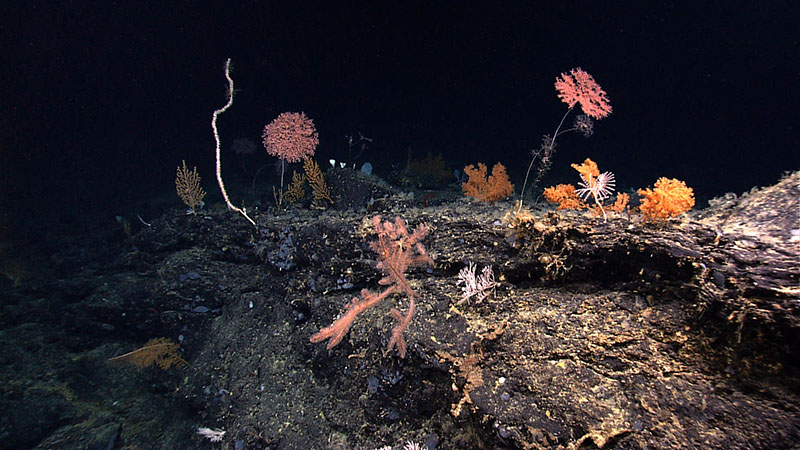

While exploring “Dumbbell” Seamount during Dive 04 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition, we observed several of these steep cliffs covered with a high diversity of sponges. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

We talk about seamount chains being stepping stones for organisms, about finding the same species along these chains and about the often-dense communities of deep-sea corals and sponges that live there. But how does that happen, when these animals can’t swim? A fish you can imagine hopscotching from one seamount to another, visiting different areas to feed and reproduce, but for those organisms that are attached to the bottom, the answer is a little more complex.

Though corals and sponges are what we call sessile benthic species, so animals that live permanently on the seafloor, they do have a mobile phase. This means that a part of their lifecycle is either up in the water column or spent crawling on the seafloor, allowing them to disperse. This mobile phase occurs when the animals are larvae, tiny round specks created by either eggs and sperm joining together or through asexual reproduction, where a part of the adult buds off and disperses. The job of the larva is to wander either ocean currents or the seafloor and find new habitat to live in, grow, and have offspring of their own. But how long do they wander for?

An example of an area of diverse deep-sea corals on the Atlantis II seamount complex. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Our Deepwater Backyard: Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download largest version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

That answer is definitely a bit more complicated, as it really depends on the species. Some corals and sponges produce larvae that immediately sink and crawl on the seafloor, and so don’t travel far from their parents to find habitat suitable to grow in. These species we’re unlikely to find widely dispersed across a seamount chain, unlike larvae that are sent up into the water column and drift with the currents. Even for larvae that drift, there is no standard time for how long the larvae travel for before they are ready to swim down to the seafloor and begin to search for a place to grow. Some might start this process after just a few days, others have even been known to swim for more than a year. This amount of time really affects where we will see species as we continue our expedition.

Larvae of the deep-sea coral Flabellum thouarsii from Antarctica. These larvae crawl along the seafloor until they reach an area where they want to settle. Image courtesy of Rhian Waller. Download largest version (jpg, 333 KB).

I’m a reproductive ecologist and exploring seamount chains for communities of habitat builders is an important aspect of what I do. By exploring new areas looking for corals and sponges, we can infer what type of reproduction a species might have, even if we aren’t lucky enough to have samples to work on in the lab. By understanding the reproduction of species, we can begin to model and form hypotheses on where larvae travel and so where new populations might be hiding in the deep. These two fields really go hand in hand and are a big reason why I’m so excited to be exploring the New England and Corner Rise seamount chains. For me it will provide another piece in the puzzle on how long these little larvae really do wander.

Published July 8, 2021