Remotely Operated Vehicles

Remotely operated vehicles, or ROVs, are submersible robots that allow us to explore the ocean without actually being in the ocean. ROVs are connected to a ship through a series of long cables called a tether. This tether transmits operative commands from the surface vessel while the ROV sends back data, including live video, of its surroundings.

Pilots examine sonar and live video data for remotely operated vehicle ROPOS from the control room onboard NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow. Image courtesy of Peter Lawton. Download largest version (jpg, 981 KB).

While ROVs continue to make new strides in technological development, they are by no means a new tool. First developed in the 1960s, ROVs were used by the U.S. Navy as a resource for national defense and underwater equipment recovery. By the 1980s, commercial companies used the robots to aid in the oil and gas industries. Now, ROVs are used across the globe for both ocean exploration and industrial surveillance, allowing ROVs to be respectively categorized as Science-Class or Working-Class vehicles.

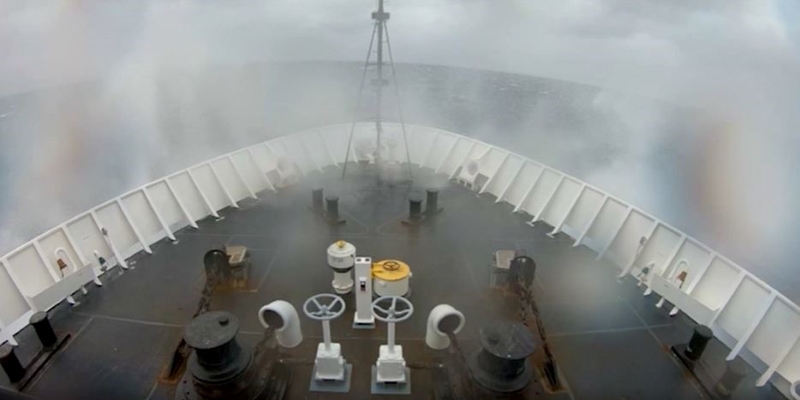

The eight-kilometer-long steel cable that connects remotely operated vehicle Seirios with NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. This tether, which is unspooled from a storage drum within the ship, brings electrical power and signals to the ROV while returning live video feeds to the ship. Image courtesy of Annie White, GFOE. Download largest version (jpg, 13.5 MB).

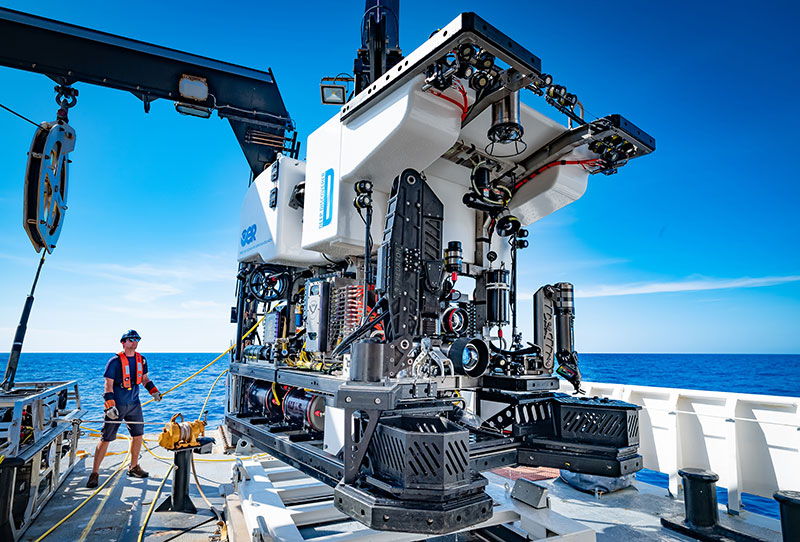

ROVs range in size. Some are as small as a laptop computer. Others are as large as a small truck. Larger ROVs are very heavy and need other equipment (e.g., a winch and an A-frame or a crane) to launch and recover them.

Pixel, a small remotely operated vehicle, on the deck of U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sycamore during the 2021 Search for the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear. Image courtesy of David Ullman, MITech. Download largest version (jpg, 304 KB).

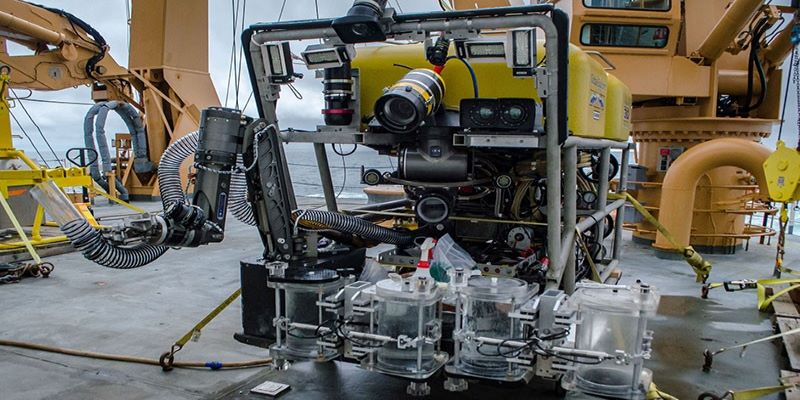

ROVs typically consist of video cameras, which transmit real-time surveillance to scientists aboard the surface vessel; lights; sonar systems; and a buoyancy foam pack, which allows the vehicle to remain light and easy to maneuver when in the water. ROVs can use external sensors that are mounted on the vehicle to measure things like conductivity, temperature, and depth. ROVs may be built with a manipulator arm designed for collecting biological and geological samples, which are deposited into boxes along the sides of the ROVs. The movement of the ROV and its manipulator arms is guided by pilots on the surface vessel via joysticks and touchscreens on a “control box.”

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer being recovered onboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer after completing 19 dives during the 2019 expedition Windows to the Deep. Image courtesy of Art Howard, Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration, Windows to the Deep 2019. Download largest version (jpg, 153 KB).

Some ROVs are built with two bodies, such as NOAA Ocean Exploration’s vehicles Deep Discoverer and Seirios. Deep Discoverer travels and samples in the water column and across the ocean floor, and is tethered to its hovering companion ROV, Seirios, which absorbs the ship’s heave to keep Deep Discoverer stable. An advantage of a two-body system is that the hovering ROV acts as an extra light source and camera, giving the pilots, scientists, and viewers an expanded view of the ocean. However, two-body ROVs are more difficult to control and transport than their single-body counterparts.

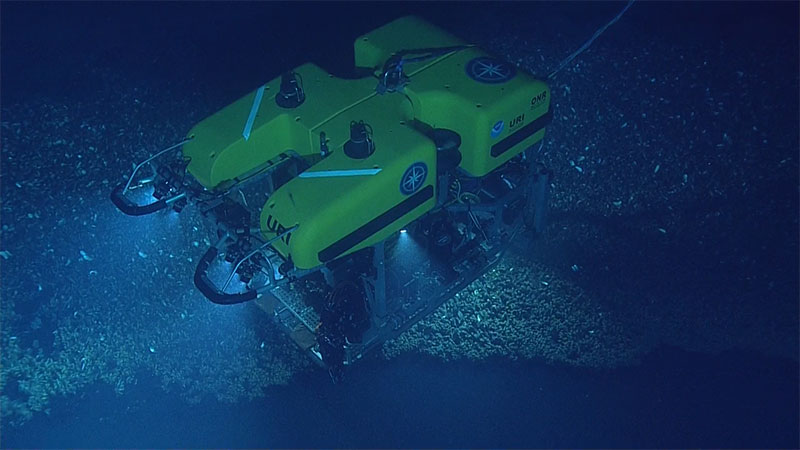

Tethered remotely operated vehicle Hercules explores the ocean floor through use of LED lights and video cameras along the front of the vehicle. Image courtesy of Inner Space Center and the University of Rhode Island. Download largest version (jpg, 941 KB).

ROVs provide scientists exceptional access to the deep ocean. The ability of ROVs to dive for extended periods makes them a versatile tool for achieving ocean exploration objectives, yet there are still significant technological advancements being made to ROVs. Brighter lights, increased data storage, and higher-quality cameras continue to be implemented in ROV updates to pave the way for a better-understood deep sea.

The Deep Discoverer remotely operated vehicle gives scientists unprecedented access to the deep ocean – from delivering stunning high-definition video and gathering physical data about surrounding waters, to allowing the collection of biological and geological samples. This in turn helps scientists to better understand an ecosystem in its entirety, meaning we can make better decisions about an area's management as well as its protection. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download largest version (mp4, 122.6 MB).