A crab megalopae (late larval stage) has a pink, crab-like body. Unlike a mature crab, however, the megalopae does not hold its abdomen underneath its body. Note the large blue eyes, which are difficult to see in this photo. Click image for larger view.

Sponge Commensals: A Life Inside Another Organism

August 21, 2004

Cara Fiore

Graduate Student

College of Charleston

All things considered, it was an exciting afternoon. A thunderstorm broke out just as we were preparing for the first dive. After waiting out the rain and lightning, the crew finally deployed the Johnson-Sea-Link II sub. Then some equipment malfunctioned, and the dive -- our first-- was cut short.

Nonetheless, the scientists and crew aboard the sub were able to collect a few sediment samples and some video footage. The Johnson-Sea-Link II is a wonderful tool for collecting samples that may otherwise be difficult or impossible to obtain. I am looking forward to my sub dive to see, first hand, what lies beneath the brilliant blue surface water.

This evening, we deployed a conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) sensor package. As the CTD descends, it collects depth, temperature, conductance, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity profiles of the water. We also deployed two types of nets to collect plankton: a bongo net and a neuston net. The bongo nets are lowered to about 200 m, while the neuston net is dragged near the surface. We caught crab megalope (larvae) that two scientists on board are planning to study, as well as very small fish and invertebrates like copepods (tiny crustaceans) and a colonial salp.

The sponge goby (Evermannichthys metzetaari) is common to South Carolina waters. Streamlined and growing no longer than 3 cm, the goby dwells in the small canals and pores of sponges. Click image for larger view.

During this expedition, I will focus on another invertebrate: the sponge. At one time, sponges were not considered living animals. Of course, they are very much alive, and their porous structures are living homes to a plethora of other organisms, as well.

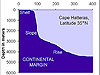

Sponges are filter-feeding animals that draw in water through their ostia (pores) to obtain nutrients from the water, which is then expelled through a larger central opening, the osculum. They grow attached to hard substrates, so they are commonly found on rocky reefs and hard bottom, such as that found on the Blake Plateau along the Latitude 31-30 Transect. A sponge skeleton is composed of calcareous or siliceous spicules, and sometimes spongy fibers. That's why some sponges (like glass sponges) may be very brittle or very tough and "spongy." Their growth forms (the shapes into which they grow) can range from encrusting to vase-shaped or branching.

The sponge's skeleton and its growth form are two of the facts that affect what types of animals inhabit the sponge. Polychaete worms (small segmented marine worms) and amphipods (small crustaceans) tend to be the most common symbionts, inhabiting the canals of the sponge as well as burrowing into the walls. Snails, crabs, brittle stars, snapping shrimps, and bivalves are also common inhabitants of sponges. These animals may not harm the sponge at all (commensal symbiosis), or they may prey on the sponge (parasitic symbiosis).

Because sponges harbor many animals at the base of the food chain, sponges are both important habitat and as an important link in the food web. Fish may prey on certain sponges as well as the symbionts found within the sponge. Some fish are found only within sponges. These include certain gobies and blennies, among which are the smallest known vertebrates.

We know little about the deep sponge community of the South Atlantic Bight, so the samples collected by the Johnson-Sea-Link II submersible will help us understand the ecology of this area. (We may even find some species of sponges or other fauna that are new to science.) During submersible dives, we plan to collect representative samples of sponges, such as tube and melon sponges.

This melon sponge, collected from the Blake Plateau, is attached to a dark manganese-coated rock. Note the large osculum on top of the sponge. Click image for larger view.

White tube sponges, showing the large central osculum and similar ostia (pores) in the body wall. There is brittle star in the sponge on the left. Click image for larger view.

Back at the laboratory, we will perform detailed analyses of the sponges. First, we will identify the sponges, using a microscope to look at the sponge spicules, which are diagnostic of sponge species. Next, we will dissect the sponge to find and identify all the fauna living within it. Finally, we will use numerous factors (depth, salinity, sponge morphology and volume, and type of environment in which the sponge was found) to describe the ecology of deep reef sponges and their associated fauna.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.