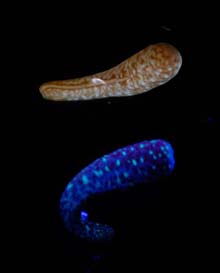

Figure 1. Zoanthid anemone larva shown in white light and with fluorescence excitation. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Blue-water Diving

July 23, 2009

Dr. Steven Haddock

Research Scientist

Bioluminescence and Zooplankton

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Dr. Alison Sweeney

University of California – Santa Barbara

Blue-water diving is a scuba diving technique used by scientists to investigate animals living suspended in the middle of the ocean. These animals are too fragile to collect with large oceanographic equipment, or even plankton nets, and their abundance and importance are often underestimated.

Blue-water diving requires some special techniques. Since there are no visual references in open blue-ocean water, you could easily find yourself shallower or deeper than you intended. To avoid this problem, we deploy a long line down from a buoy, and attach a "trapeze" to this downline. We then tether ourselves with 9-meter (30-foot) lines to the trapeze. Each diver from the group takes turns being the "safety diver," serving as the buddy for the other divers who are focused on their work. The safety diver stays close to the trapeze, tending the lines and keeping an eye out for sharks or other predators in the area.

Those who've experienced blue-water diving tend to feel that the experience of being suspended in the three-dimensional outerspace-like world gives them an irreplaceable perspective on planktonic life and oceanographic processes. However, this Ocean Explorer cruise focuses on benthic bioluminescence, and benthic means living on the bottom. Since the bottom here is about 600 to 700 m (2,000 to 2,300 ft) deep — far, far deeper than it is possible to scuba dive — why might we want to conduct blue-water diving operations on this cruise? The answer is that we can learn a lot about animals living on the bottom, and their bioluminescence, by studying the water above it.

The scuba dives so far have not revealed the great diversity that we know can occur in these waters. We are hoping that tomorrow's station contains more of the oceanic species we have been expecting. That is not to say that we haven't had interesting results from our scuba operations. Dr. Alison Sweeney is one of the most experienced and observant blue-water divers on board the ship. Yesterday she found a very strange creature about the length of a pinkie fingernail that looked sort of like a brown, spotty comma. We didn't know right away what it was, but often researchers collect first and ask questions — such as "What is it?" — later.

Turns out, it was the larval version of one of the most abundant bioluminescent animals we have been finding on the bottom on our earlier dives. Many benthic organisms, including this bioluminescent anemone, spend their early life stages in the water column as plankton. This one, in particular, was covered in fluorescent spots, quite unlike its initial drab appearance. One of its parents could easily have been one of the anemones we observed on our previous sub dive.

It is interesting that the same fluorescent and bioluminescent proteins are apparently active in both the larval and adult forms of the animal. Although we generally assume that luminescence functions in the adult forms, it is also possible that it serves important roles during the planktonic dispersal phase (figure 1).

Fluorescence and bioluminescence may occur independent of each other, as in the case of the fluorescent bristles on a crab, but they can also be linked to each other (figure 2). One such example is a small siphonophore, which spends its entire life as plankton. This species has green fluorescent spots along its stem, and it is also bioluminescent (figure 3). We look forward to future dives to see what new kinds of drifters we will encounter. . . .