By Dr. Andrew Thurber, Assistant Professor, Oregon State University

September 30, 2020

While exploring in and near the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, our team came across many unique features and animals found within the steep walls of Quinault Canyon, a region that is also within the protected harvest areas for the Quinault Indian Nation. Working with Oregon State University researchers funded by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, the team aboard Nautilus conducted extensive sampling of these methane seep regions. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 148.6 MB).

We often think of exploring as diving into the abyss to find new species. And while we do find new species, exploration is really one of the first and most critical components of the scientific method: observation.

If there is one thing I have learned in science, it is that the most significant advances come when you are wrong. Numerous times during this cruise, I was able to visualize how my view of the ocean was wrong, based on new observations of the seafloor. These glimpses into the deep further shaped my view of methane release in a way that will direct my future research, including research using the samples collected on this expedition.

I expected the seep sites to look… well like this:

This otherworldly seep was found with large craggy rocks expending out in many directions, providing lots of places for animals like sponges, mushroom corals, and crabs to perch on at this 1,000-meter (3,000-foot) deep seep. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 48.6 MB).

Expansive mud, carbonate blocks, clams, maybe a hydrate or worm cluster. And we did find those things. They were critical to getting good samples to advance the goals of our research. Plus, as a connoisseur of mud - they were superb. Who doesn’t love a 50-meter (164-foot) diameter microbial mat?

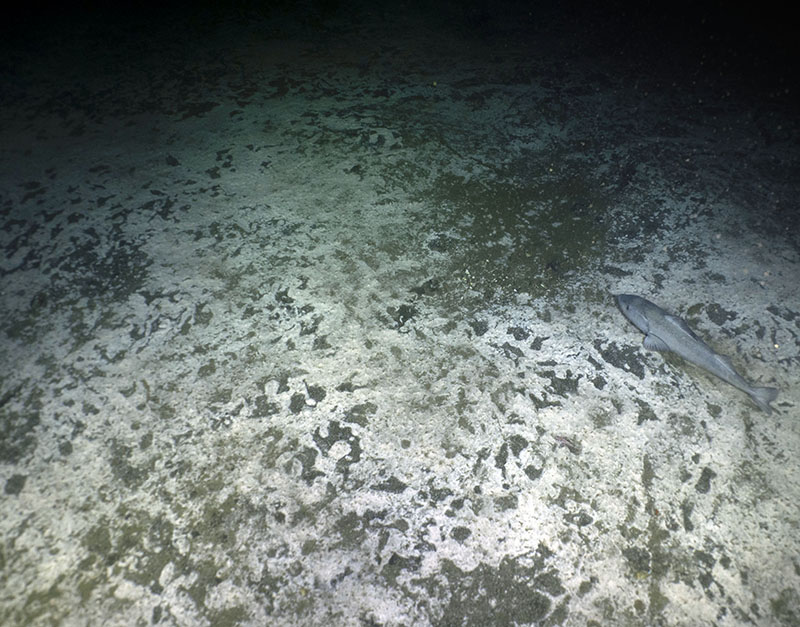

During one of our dives, we found an expansive microbial mat. One of the largest continual microbial mats I have ever seen and there were many different types of life around it, including this sablefish (black cod). Image courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (jpg, 4.5 MB).

Yet, on multiple dives, we also found seeps that did not look like this. Little pockets of seepage that appeared widespread and like ghosts in the multibeam. Ephemeral and yet enduring. In one case, we found a wall of seeps with none of the large animals (clams, worms) that could be taking advantage of this food from the deep.

Many little pockets of microbial mats, indicative of methane seepage from beneath, were present throughout multiple dives from 200-500 meters (656-1,640 feet) water depth. Video courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (mp4, 44.2 MB).

These seeps were also shallow seeps — at 200 meters (656 feet), the seeps were little bubble sources. This is really intriguing as recent work has shown that these shallow seeps (and I consider 200 meters shallow) are incredibly abundant on the coast. From this cruise, I learned that these seeps are not (at least as we saw) discrete pockets into Earth but instead a sponge with many little pores leaking energy into the ocean.

We have been aiming to quantify the “sphere of influence” of seeps, viewing them as a point source of release that impacts a three-dimensional sphere of the ocean. Instead, we saw a wall of energy, and if our observations are not unique, this may require us to reenvision how we approach exploring, studying, and quantifying seeps and ocean ecosystems.

Seeps are just one of the many diverse habitats that together form the ocean ecosystem. However, they are not the only habitats that add to the diversity of the deep sea. Sponges, like this one hanging from a near-vertical side of a submarine canyon, also add to the diversity, beauty, and opportunities for discovery in the deep. Image courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (jpg, 3.5 MB).

I love being wrong. Every misstep is a step that leads us back to the drawing board. Only through exploration, observation, and a consistent re-evaluation of what we “know” can we learn how the world really works. While we met the expected cruise aims that we embarked to accomplish, our unexpected discoveries will advance our understanding of seeps in the ocean and of oceans in general.

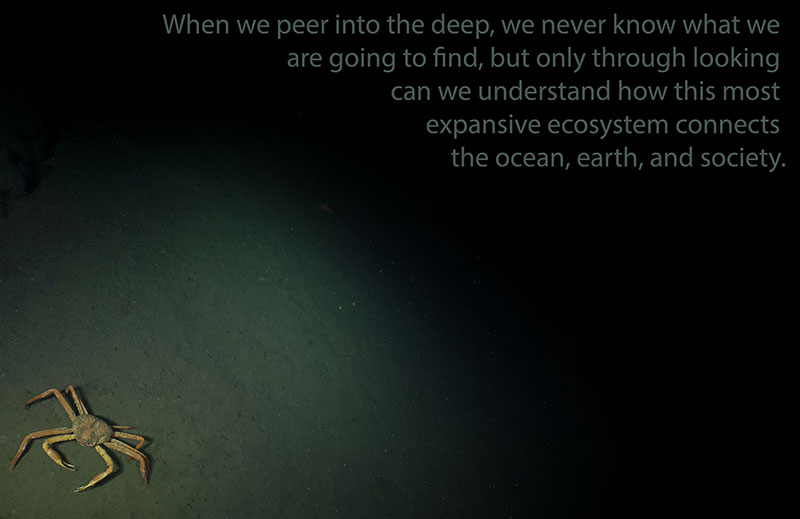

Tanner crabs joined us throughout our dives, reminding us of the link between seeps, the deep sea, and the food we harvest from it. Image courtesy of Oregon State University, NOAA OER, NOAA OCNMS, Ocean Exploration Trust, NA-121. Download larger version (jpg, 4.6 MB).