2022 ROV and Mapping Shakedown

February 23 - March 3, 2022

Industry’s Place in U.S. History: The Maritime Legacy of African-American and Indigenous Peoples

On February 25, 2022, NOAA Ocean Exploration and partners from SEARCH Inc. and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management discovered the remains of what is likely the brig Industry. The article below describes Industry’s role in African-American and Indigenous people’s maritime history.

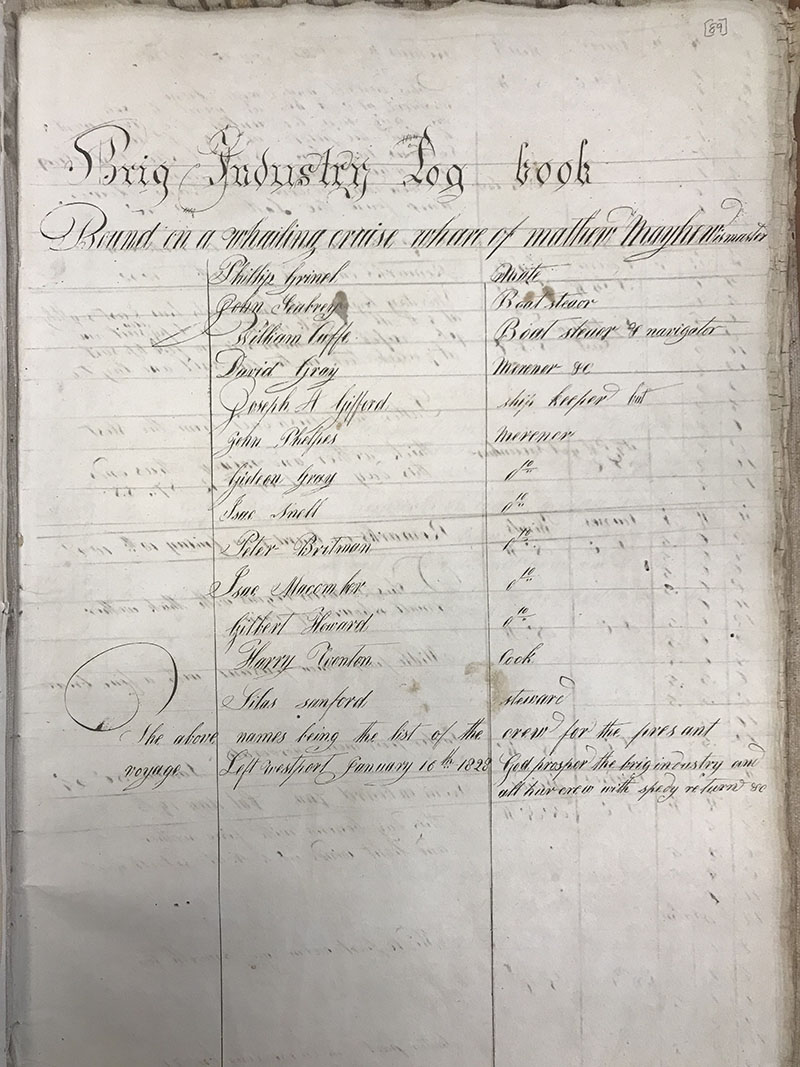

In addition to Industry’s community ties to its home port of Westport, Massachusetts, the brig, like many other American and local whalers of its time, was powerfully connected to the African-American maritime community. The voyages of Industry included African-American crew members, a number of whom were children of marriages between enslaved and free Blacks in the community and the neighboring tribes of New England. These tribes had hunted whales and introduced the first colonists from England to the practice.

There was a substantial presence of Afro-Indigenous individuals in the whaling industry that persisted throughout the 19th century. Among them was Pardon Cook of Westport “who commanded more whaling voyages than any other person of color in the nineteenth century,” according to historians. Cook followed the tradition set by his father-in-law, African-American whaling captain Paul Cuffe of Westport, whose whaling career began in 1775 when he joined a ship, as he wrote in his autobiography, “at the age of 16, as a common hand on board of a vessel destined to the Bay of Mexico, on a whaling voyage.”

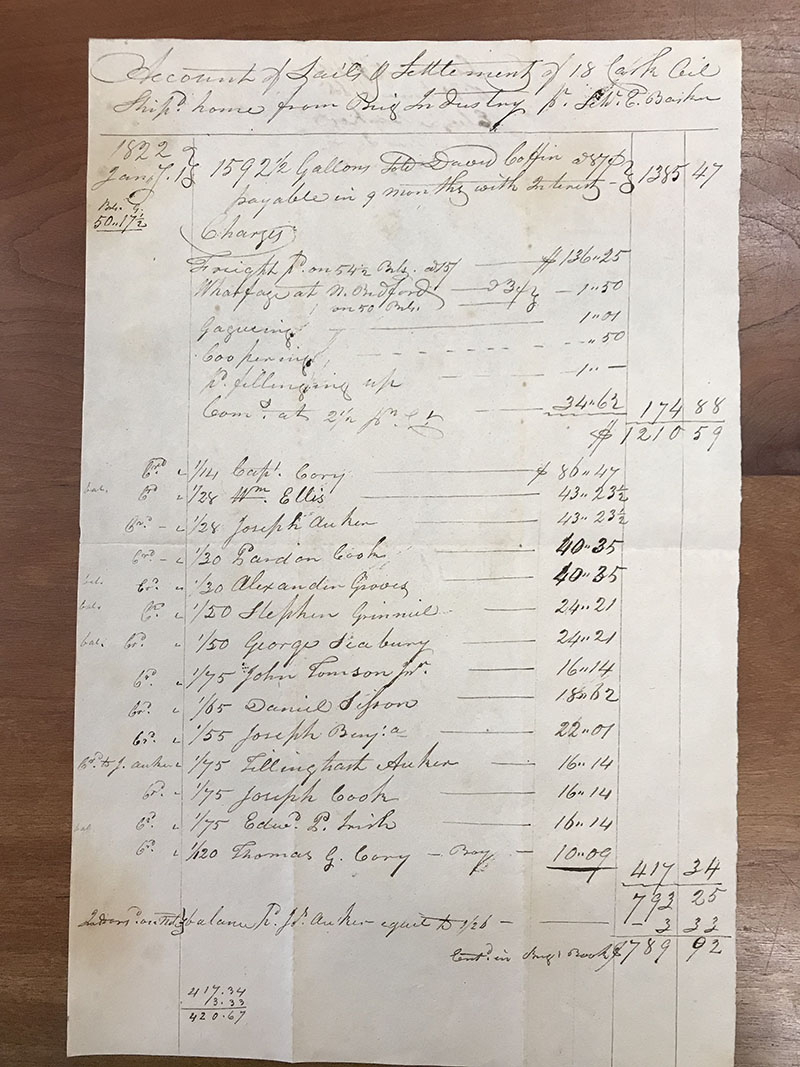

Cook first went to sea with Cuffe on the brig Traveller in 1816 as second mate. In all, Cook made 11 whaling voyages, either as an officer or in command of the whaler he was sailing. Two of these, in 1819 and then again in 1821, were as second mate on Industry.

Cook wasn’t the only Cuffe family member to sail on Industry. William Cuffe, Paul Cuffe’s youngest son, sailed on Industry in 1828 and 1832.

The “Cuffe dynasty” was actively engaged in whaling as well as other maritime enterprises, including partnerships with Isaac Cory, Sr. and the Cory family. The Corys owned Industry and were partial owners of Paul Cuffe’s brigs Hero and Traveller.

Crew lists for Industry offer some details about the crew members who sailed aboard the brig during its two-decade career, but a list of the crew who were aboard when the brig was lost in 1836 has not been found.

In lists from 1816 to 1834, diversity among the crew is denoted by terms such as “dark” or “black,” with other individuals described as “yellow,” and “mulatto,” with “black,” “curley,” or “woolly” hair. These details, as well as the relatively young age of the crew members, many of whom were teenagers (counted as men in that period), provide insight into the human side of the ship and its crews and especially of the diversity of the men on board.

It is important to note that multiracial crewing of whalers like Industry provided a powerful haven for African-Americans. Ashore, even as free men, they lived in a nation where slavery was legal and restrictive laws and regulations governed the conduct and restricted the liberty of free people of color.

Imagine what it must have been like for the crew of Industry and other ships when sailing as free men from Westport and landing at American ports, sometimes for extended layovers, where slavery existed. Kidnapping was an ever-present fear, and laws, ambiguously referred to as “Seamen Acts,” restricted their movements and required local law enforcement to arrest free Black seamen who left their ships and confine them in port. These seamen were required to pay fees for their imprisonment, and unpaid fees put free Black seamen at risk of being sold into slavery to satisfy their “debt.”

What must have been going through the minds of Industry’s crew when trouble brewed, seventy miles out, in a stormy Gulf of Mexico? What was the greater fear, trying to row for shore in their failing ship or being picked up by a passing ship headed for a Gulf port? Fortunately for Industry’s crew, the whaling brig Elizabeth, also of Westport, was close by and rescued all aboard and returned them to their home port.

While Industry itself never made it home, more than 180 years later, we now know its likely final resting place and are able to share this important piece of history.

Related Links

- Proving a Discovery: The Case for Industry

- Setting the Stage for Discovery: Whaling in the Gulf of Mexico

- NOAA, Partners Discover Wreck of 207-Year-Old Whaling Ship in Gulf of Mexico

- Industry (BOEM Wreck Site 15563) Photogrammetry Model

Published March 23, 2022

Contributed by: James P. Delgado, SEARCH Inc.

Relevant Expedition: 2022 ROV and Mapping Shakedown