This purple specimen of Clavularia is an octocoral that lives on the dead skeletons of bamboo coral. The orange brittle stars also call this home. Photo by L. Rear. Click image for larger view.

Back to Bear Seamount

July 17, 2003

Diana Payne

Connecticut Sea Grant

The sea isn’t a place but a fact, and a mystery

Under its green and black cobbled coat that never stops moving.

![]() Take a closer look at coral polyp patterns. (mp4, 2 MB)

Take a closer look at coral polyp patterns. (mp4, 2 MB)

Today’s dive took DSV Alvin pilot Tony Tarantino, Pilot in Training (PIT) Anthony Berry and Dr. Jon Moore to Bear Seamount, which rises approximately 1838 m above the abyssal plain. Bear is the first seamount in the New England seamount chain, and emerges out of the continental rise.

Dive number 3905 again brought back beautiful corals and other invertebrates for the science team to investigate. Close scrutiny of the corals reveals many features of physical and biological adaptations to life on a seamount. Juxtaposed against what we know about shallow water corals, these observations may help unravel the multiple layers of biodiversity in the seamount landscape. Dr. Les Watling and his team are looking at microscopic coral structures in hopes that it may help us understand the big picture.

This morning, upon reaching the dive site, the occupants of the submersible found themselves on a muddy slope. As they continued to move along the seamount, they encountered many animals, including corals, fish, and sea urchins. Alvin pilot Tony Tarantino asked observer Dr. Jon Moore, "Ok, what do we do next?” Looking to obtain observational data for species abundance and diversity and to collect invertebrate specimens, Dr. Moore replied, “Oh wow! It’s time for a shopping spree!”

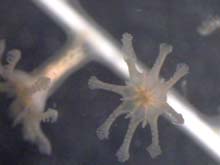

An open coral polyp as seen by the Alvin, showing the tentacles and some pinnules. Photo WHOI. Click image for larger view.

Octocoral Polyps

Maya Crosby

Lincoln Academy, Newcastle, Maine

Dr. Les Watling

University of Maine

In an octocoral, the polyp is the individual of the colony - the soft, living part of the coral that resides in the hard calcareous skeletal structure. The polyps are responsible for feeding, reproduction and defense. Dr. Les Watling, an octocoral biologist from the University of Maine, describes the polyps as being like small, individual sea anemones that make up the body of the octocoral.

The colony needs all of its polyps to work together to get equal amounts of food. The tentacles of each polyp extend to form a continuous filtering net. Scientists can look at close-up video of coral polyps and see the tentacles extended so that they nearly touch tip to tip. In Iridogorgia sp. the polyps are arranged in a long line, slightly offset from each other, so that a localized turbulence of water is generated. In Metallogorgia, the pinnules (small branches on the tentacles) are very thin and the polyps are arranged such that the tentacles form a three-dimensional net. The seawater flows past or through the net and allows the animal to feed more efficiently. Researchers like Dr. Watling are interested in knowing to what extent the spacing affects turbulence on a small scale. With many thin finger-like extensions filling the inter-tentacle space, the water flow moves around the polyp as if it was a solid surface. The fluid becomes more viscous, like molasses. The water stream becomes hard to move through for small particles and these viscous forces benefit the coral, trapping more particles in the path of its tentacles.

Inside the polyps, or arranged around them, are small pieces of hard calcareous tissue called sclerites. Sclerites provide structure and defense to the polyp. By examining these sclerites, Dr. Watling may be able to learn more about the ecology of the polyp and coral identification and taxonomy.

Polyps play an important role in coral taxonomy. The classical system of taxonomy is based on the design and arrangement of the sclerites. New methods that use mitochondrial DNA show a different phylogeny that disagrees with the sclerite data.

Dr. Watling states, “One of the problems in developing a morphology based classification system is that the entire morphology is not used. One of the ways we could improve the system is to use additional morphology information such as how eggs are produced.”

No one has yet looked at the morphology of deep-water gorgonian reproduction. Graduate student Anne Simpson is collecting octocorals on this cruise to gather the kind of ultrastructural information that would be needed to improve morphological taxonomy.

Polyp reproduction is also of interest to coral biologists. The reproductive part of the polyp is near the base. The eggs develop in septa, dividers of tissue in the mesentery portion of the polyp. Dr. Watling explains that the way an animal makes its eggs provides information about its evolutionary history, because that portion of the animal’s physiology tends not to change over time.

Dr. Watling says, “The reason I wanted to dive with Dr. Scott France was to benefit from his broader background in taxonomy. These are the best close-up video clips of a living deep sea coral that I know of,” he explains. “There are other videos of entire colonies that show shape and color – however, this doesn’t help us know more about the biology of each animal.” Scientists are also able to make actual recorded behavioral observations because they often have nearly six hours of observation time.

Thus, polyps are possibly the most important part of the deep sea coral for scientists to study. Using tools such as close-up Alvin dive video they can learn much more about coral feeding behavior, reproduction, and taxonomy. Coral biologists are also exploring whether the tentacles flick particles into the mouth.