Outcrop of white gas hydrate at Blake Ridge is building "down," like a stalagmite in a cave, as methane bubbles rise up, hit the overhang and instantly turn to hydrate. Click image for larger view.

'Hydrate Hunting' on Blake Ridge

September 27, 2001

Paula Keener-Chavis, Director

South Carolina Statewide Systemic Initiative's Charleston Math and Science Hub

Deep East Education Project Coordinator

I have made friends with the sea; it has taught me a great deal. There is a kind of inspiration in the sea. When one listens to its never-ceasing murmur afar out there, always sounding at midnight and mid-day, one's soul goes out to meet Eternity. -- L.M. Montgomery, Along the Shore

Dr. Barun Sen Gupta filed the following report on the R/V Atlantis at 8:30 a.m. this morning: "After we completed our sampling, we went hydrate hunting and came upon a large crevasse where the sediment layers stuck out. As we went over this ledge, we could see really good layering of the sediments -- the layers were about 0.5 m thick. Beneath the layers we saw ice. Other indicators of hydrate were bubbles coming out of the sediment. As we probed the sediment, more bubbles started coming out. We took a core sample of the sediment and the core definitely had hydrate in it because it bubbled all the way up as Alvin rose to the surface. There was a gap between the ice and the sediment, and shrimp crowded under the hydrate. We did not see any hydrate on the surface or deeper in the depression, just where we found the chaotic arrangement of the sediment layers."

Alvinocarid shrimp hover under a ledge composed of mud and gas hydrate on the Blake Ridge. These shrimp are a common component of chemosynthetic communities at vents and seeps. Click on this image for a video clip.

Other findings included at least 100 live clams, flatworms living on the dead clams, large mussels, and benthic forams. After the science meeting, everyone went about the daily routine of preparing for the samples that Alvin will deliver and securing samples collected from the previous day's dive. The video monitors played continuously as the ocean floor and its inhabitants were displayed for all to see.

The Zodiac was lowered over the starboard side into the water at 5:14 p.m. and sped away to meet the orange fin of the Alvin submersible as it slowly emerged to the surface. A diver jumped from the Zodiac into the water to hook a line from the Atlantis to Alvin. He surfaced, gave an affirmative signal, and 4 min later, the A-frame on the Atlantis hauled Alvin back on board.

Dr. Bernhard's Samples

Dr. Joan Bernhard rushed from the submersible to the cold room to process her sediment core samples. In the ship's cold room, which maintains a temperature of 34 degrees F, she lifted a clear Plexiglas cylinder about 25 cm in length that held a 7.5-cm core of sediment collected by Alvin from the deep ocean floor. It's a beautiful cylindrical "aquarium" containing a cross-section of the sediment lying just beneath the surface.

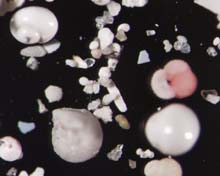

Microscopic shells in sea-floor sediment collected from Blake Ridge. The large, round shell at top left is a planktonic pteropod about 0.25mm across. The triangular shell immediately underneath is a benthic, or bottom dwelling, foram, Bolivina. The other larger shells, including the pink one (Gloobigerinoides), are planktonic foraminiferans. These shells have fallen from surface waters to the sea floor. Click image for larger view.

Floating at the surface/water interface in the Plexiglas cylinder was a strange-looking deep-sea protozoan, light beige in color and about the size of a golf ball. Dr. Bernhard gently scooped it out with a spoon from the galley and placed it in preservative in a small jar. "Xenophyophores," she said. "These single-celled organisms are common in the deep sea, but this is the first time they have ever been seen at a seep site. They are extremely fragile and no one knew what they were until the early 1970s." It's hard to believe that such a large organism consists of one single cell. Dr. Bernhard said that very little is known about their biology.

The remainder of Dr. Bernhard's samples were preserved in 1-cm sections down to a depth of 3 cm of the core sample. She sat bundled up in her fleece jacket with a colorful scarf wrapped around her neck at the computer in her lab. Although cold and tired after a long day's work, she was surely pondering the significance of her new discovery today on Blake Ridge.

(top)

Wayne Allen Bailey, bosun (boatswain)

Interview with Wayne Allen Bailey

Bosun (Boatswain)

Ocean Explorer Team: What is your job here on the Atlantis?

Wayne Allen Bailey: I'm responsible for loading, unloading, securing, deploying, and recovering science gear. I am also the deck foreman for maintenance. Basically, I am the equivalent of a sergeant in the Army. I started working on the Atlantis II back in 1983. While it was in Woods Hole being converted, I was hired to do rigging, sandblasting, crane operations, chipping and painting, and general ship maintenance. I transferred over to the Atlantis when the Atlantis II was sold. The last I heard, the Atlantis II was auctioned, bought back by the owner, and in New Orleans. She was a good 'ole ship.

Ocean Explorer Team: What kind of schedule are you on with your job, and what do you do when you are on leave?

Wayne Allen Bailey: I work a four-months on, two-months off rotation. When I'm at home, I work around the house. I really enjoy spending time with my three daughters and five grandchildren. I'm a huge football fan! I love the game. When I graduated from high school, I was the 4th graded linebacker in the nation. I had scholarships to go on, but I seriously injured my knee and shoulder in a game and couldn't play any more.

Ocean Explorer Team: What is the most important part of your job?

Wayne Allen Bailey: Maintaining a feeling of teamwork, camaraderie, and fellowship.

Ocean Explorer Team: What is the most important thing you learned in school that has helped you in your job?

Wayne Allen Bailey: To be a good person, to know that no one is right all the time, and that it is more important to be fair in your dealings with others.

Giuliana Panieri, research associate

Interview with Giuliana Panieri

Post Ph.D Position at the University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Ocean Explorer Team: What is your role on this expedition?

Giuliana Panieri: I am a research associate working with Dr. Barun Sen Gupta. I got funding from the Italian government to come from Italy and participate in this expedition. I help Dr. Sen Gupta with sample collection and preparation. I will analyze the samples to determine species composition and the taxonomic structure, and compare these findings to the benthic foraminifera from samples collected in the Adriatic Sea. There are methane seeps in the Adriatic, and I have been studying the benthic foraminiferans there. I have used my findings to reconstruct the history of the release of methane in the stratographic record.

Ocean Explorer Team: As a research associate, what is your perspective on the expedition?

Giuliana Panieri: I think that this is one of the best and most important experiences in my life, both for me personally and for the research that I am doing. I hope that this experience will enable me to do this kind of research in other parts of the Mediterranean. Back in Italy, I am one of the first scientists to study the relationship between benthic foraminiferans and hydrocarbon seeps in their actual environment. I gained much of my knowledge from papers authored by Dr. Barun Sen Gupta, Dr. Paul Aharon, Dr. Joan Bernhard, and Dr. Cindy Van Dover. This expedition provides me with the opportunity to interact with these scientists who share similar research interests. It also gives me the opportunity to work with them in the field.

Ocean Explorer Team: What influenced you to study ocean sciences?

Giuliana Panieri: I am attracted to the sea and the ocean. If you consider that the majority of Earth is formed from sea sediments, and if you understand the mechanism that controls the modern environment in the sea, then you can use this information to explain what has happened in the past.

Ocean Explorer Team: What do you hope to do when you finish your current position?

Giuliana Panieri: I hope to continue this kind of work, because this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.