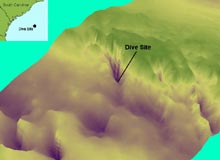

Scientists used multibeam bathymetric data to create a 3D view of a portion of the Charleston Bump. This image shows the target location for today's submersible dive, relative to the South Carolina coastline. Image courtesy of Phil Weinbach, SCDNR. Click image for larger view.

Sucked In and Spit Out!

August 5, 2003

David Wyanski, Fish Biologist

Phil Weinbach, Fish Biologist

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

An exploration is a voyage into the unknown. When seeking new destinations you are never quite sure what the conditions will be or what you will encounter. Surprises always await you, no matter what upfront knowledge you think you may have. With any journey into the ocean depths, some level of risk is inevitable, particularly when investigating an area as dynamic as the Charleston Bump.

To select the location for today's dive in the Johnson-Sea-Link II submersible, we supplemented a three-dimensional GIS view of the Charleston Bump with depth information collected from the ship’s fathometer. We used these data to identify a target location with high relief, an area that we believe may provide habitat for interesting fish and invertebrates.

The Charleston Bump complex causes the Gulf Stream to speed up and be deflected offshore. Even when the weather is beautiful, waters deflected off the Bump often result in standing waves and whitewater immediately adjacent to glassy seas. Click image for larger view.

Despite the available information, hitting our projected dive target sometimes involves as much good fortune as skill and prowess. The same swift and constantly changing currents that make life a challenge for fishes and invertebrates on the Bump will spin, push, pull, and slide the sub off course. Currents at the surface and those at depth may rush at different speeds and in drastically different directions. With the equipment currently aboard the ship, there is no way for us to know the speed and direction of currents through the entire water column. In many situations, picking the dive target on the sea floor is much easier than estimating where to launch the sub in the water to hit that target.

Even with all of these complications, today’s events caught us by surprise. Our dive objectives were to investigate the geology and fauna of a steep, rocky scarp (a sharp rise in the bottom) approximately 1,500 ft beneath the sea surface and collect some representative rocks, sediments, invertebrates, and fishes. It is on these steep scarps that the large (30-100 lb) wreckfish we’ve been searching for are found.

David Wyanski, co-author of this log entry, prepares to enter the Johnson-Sea-Link II submersible prior to today's truncated dive. Click image for larger view.

After we climbed up into the sub and locked the hatch, the ship’s A-frame lifted us off the deck. Soon, we were all eager to descend, not only to see what the bottom would reveal, but also to cool off from the sauna-like temperatures quickly heating up the interior of the submersible.

Once we submerged, all became quiet and peaceful. About 20 min later, as we descended through 1,300 ft, the sub pilot, Craig Caddigan, turned on the outside lights. Blackness surrounded us. At 1,400 ft, Craig noticed a bit of backscatter from the lamp. Since we didn’t expect the sea floor for another 100 ft, we continued to descend despite poor visibility. Intuition and a nagging feeling, however, convinced Craig to turn on the sub’s laser beam. The green beam immediately reflected off the hard bottom. Craig suddenly realized that we were a mere 3-4 ft above the rocky ocean floor. He stopped our descent just before we hit bottom. We had just enough time to realize that strong currents must have pushed us far from our desired target.

Looming in front of us was a steep, scraggly scarp. Even at 1,422 ft, the current was remarkably strong and effectively pushing us backwards. Immediately, Craig turned all of the power "down and forward" to fight the current, but it was useless. With full power ahead, the sub continued to drift blindly backwards at 1.5 knots. We were in a very dangerous situation. There was no telling what was behind the sub in this steep environment. At 1,400 ft, if we got into trouble, help wouldn’t be arriving anytime soon.

With rope in hand, sub crew member Jim Sullivan (you can see his bottom half) dives from the R/V Seward Johnson to "hook" the resurfaced submersible. Due to the ripping Gulf Stream current, his timing must be perfect. Click image for larger view.

Instinctively, Craig blew out some ballast to get us further off the bottom and made one last assessment of the situation. He knew in a matter of seconds that the dive could not continue. Conditions simply were not safe on the underwater mountain.

We slowly ascended from the depths. Though disappointed with our 30-sec stay at 1,400 ft, we were happy to have traveled so far beneath the ocean we love so much. It would have been nice to achieve the objectives of the dive, but more importantly, we were safely on our way home. After all, how many people can say they have been in a submersible more than 1,400 ft beneath the ocean surface?