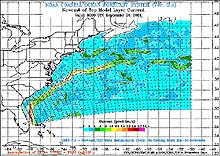

This image of surface currents illustrates the northeasterly flow of the Gulf Stream. At the edge of the continental shelf off North Carolina, the warm Gulf Stream waters mix with deeper, cold-water currents flowing south, creating concentrations of plankton and small species of fish and invertebrates that provide food for larger species. Click image for larger view.

Charismatic' Megafauna of the North Carolina Shelf

September 22, 2001

David Lee

North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

John McDonough

Project Manager, Islands in the Stream Expedition

National Ocean Service, Special Projects Office

The distribution and abundance of seabirds, marine mammals, and turtles off the coast of North Carolina may, at first glance, appear to be random in nature. If one observes closely, however, a pattern begins to emerge -- one based on the underlying topography of the continental shelf and slope, and the mingling of oceanic currents. At the shelf edge, the sea floor begins to slope away into the ocean depths, where the warm waters of the Gulf Stream collide with the deeper cold-water currents flowing south. Often, the result is a series of huge eddies and rings, some of which may persist for weeks or even months, which serve to concentrate plankton and small species of fish and invertebrates that provide food for larger species. The shelf edge, the Gulf Stream edge, the edges of eddies and upwellings -- all represent an abrupt change in conditions, and all are well recognized as sources of sustenance by seabirds, marine mammals, and sea turtles.

Seabirds

A wide and fascinating variety of seabirds can be found anywhere along these edges. As a reflection of the interaction of warm and cold currents, seabirds often include a mixture of temperate, boreal, and subtropical species, some of which are only regularly observed here or on their breeding grounds. This is especially true during times of migration, when summer seabird specie, such as white-tailed and red-billed tropicbirds, may be encountered, along with winter visitors, such as dovkies and razorbills, in addition to year-round residents, including petrels and shearwaters. In a single day, observers n this area have noted birds from the Mediterranean Sea, Greenland, the South Polar Islands, islands off the African coast, the Alaskan tundra, the Caribbean, and the U.S. Southeast!

The seabirds that forage here use visual clues or their sense of smell to locate prey. Mixed flocks can often be found in places where feeding schools of fish drive smaller bait fish to the surface, as well as around mats of the ubiquitous, giant Sargassum seaweed, which provides food and shelter for a variety of small fish and invertebrates. Some species, such as terns, jaegers, and gannets, may fly at great heights searching for signs of food, then plunge into the water to secure their prey. Other species are more solitary in nature and travel singly or in small groups, flying only a few feet from the surface and dipping their bills into the water as they feed.

The diversity of seabird species utilizing this habitat is greater than at any other area along the U.S. East Coast. It's no wonder, then, that the area also attracts and concentrates another species, known throughout the world as the "Birdwatcher."

Cetaceans

Cetaceans are marine mammals that spend their entire lives in the marine environment. They are classified as the suborder Mysticeti (baleen whales, such as the humpback), which consume zooplankton and small fish and shrimp by filtering volumes of water through their baleen plates, and Odontoceti (toothed whales, such as the sperm whale), which consume larger prey, such as fish and squid. The Odontoceti also include the family Delphinidae, represented by such species as the orca and pilot whales, as well as the dolphins. Cetaceans are built for swimming and diving, with strong flukes (tails) and streamlined bodies to propel themselves through the water.

As with the seabirds, many species of cetaceans congregate along the shelf edge eddies off the North Carolina coast to feed on the concentration of organisms. One such species is the short-finned pilot whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus), several of which have been observed during this mission swimming slowly at the surface in pairs or small pods. These whales are almost entirely dark brown or black, and grow to a maximum length of 20 ft. Feeding primarily on small fish and squid, they focus on the edges of currents, and also hunt along submarine canyons and ridges. Another common Delphinidae observed in high numbers during this mission is the Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis). These tri-colored, heavily spotted dolphins often travel in groups of more than 100 individuals, and associate with smaller pods of short-finned pilot whales, hunting and consuming similar species of small fish and squid. The Atlantic spotted dolphins are fast and acrobatic, riding the bow waves of passing vessels and leaping high into the air as they travel.

Population estimates for cetaceans are often difficult to determine and to track over time. Scientists speculate that variations in population and distribution are commonly associated with seasonal and annual shifts in food sources. Sometimes, both dolphins and whales are caught incidentally by fisheries that focus on harvesting the same food sources.

Sea Turtles

Marine turtles are reptiles that spend most of their lives at sea, foraging for a variety of foods including sponges, crustaceans, mollusks, and jellyfish, and returning to shore only to mate and lay their eggs. Newly hatched young, emerging from sand-covered nests high on shore, run a gauntlet of terrestrial, avian, and marine predators. They struggle across the beach and through the surf, finding relative protection amongst floating mats of Sargassum, where they feed on small fish and invertebrates as they grow. Although typically found fairly close to shore in waters as deep as 300-400 ft, three of the five species of marine turtles found in the South Atlantic Bight -- the leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), loggerhead (Caretta caretta), and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) -- also associate with the offshore eddies of the Gulf Stream, feeding on the rich concentrations of food there. This is particularly true of the leatherback, which is a strong swimmer (recorded at 10 knots), and which has been known to dive to depths of more than 4,000 ft.

The North Carolina shelf edge is, indeed, a unique area, both in terms of its productivity and its ability to sustain a wide variety of species, from the smallest planktonic organisms to some of the largest whales, and from the deepest benthic creatures that burrow in the sea-floor mud, to the high-flying seabirds that search the ocean surface for a meal.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.